Still the same story: strong growth, low inflation, exuberant stock markets

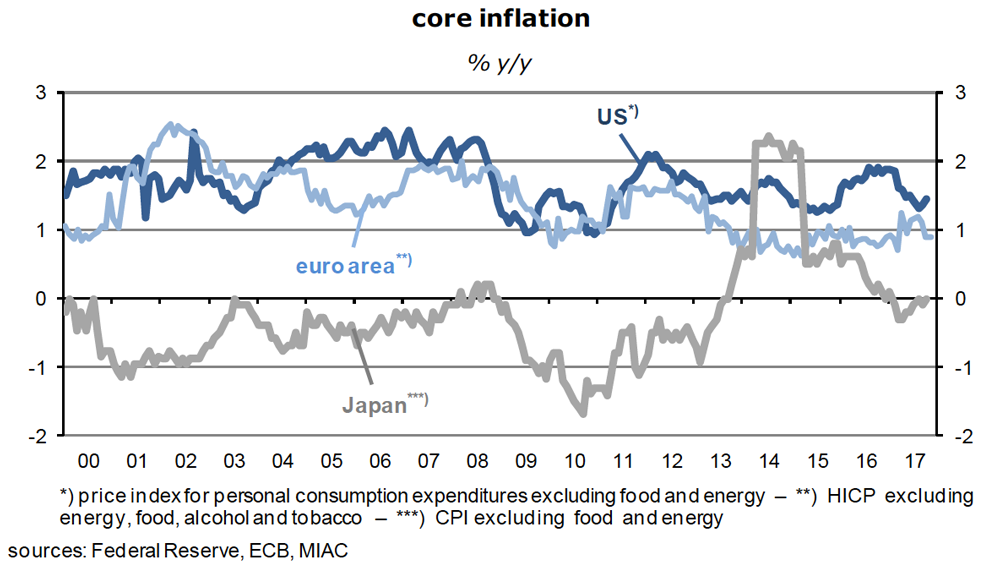

- Since inflation is mostly well below target in industrialized countries, central banks remain in expansionary mode. In spite of robust economic growth real policy rates are either negative or close to zero. Moreover, pro-cyclical monetary policies will continue until there is clear evidence that inflation is back for good. So far, such evidence is lacking.

- Financial investors get nervous when they look at the high prices of stocks, bonds and real estate, but they hesitate to take profits because growth, inflation, corporate earnings and interest rates, the main fundamentals, are extremely favorable. For the time being, setbacks are usually quickly reversed by the many cash-rich bottom fishers – who must be praying, though, that they will be able to get out of the door when the next crash arrives.

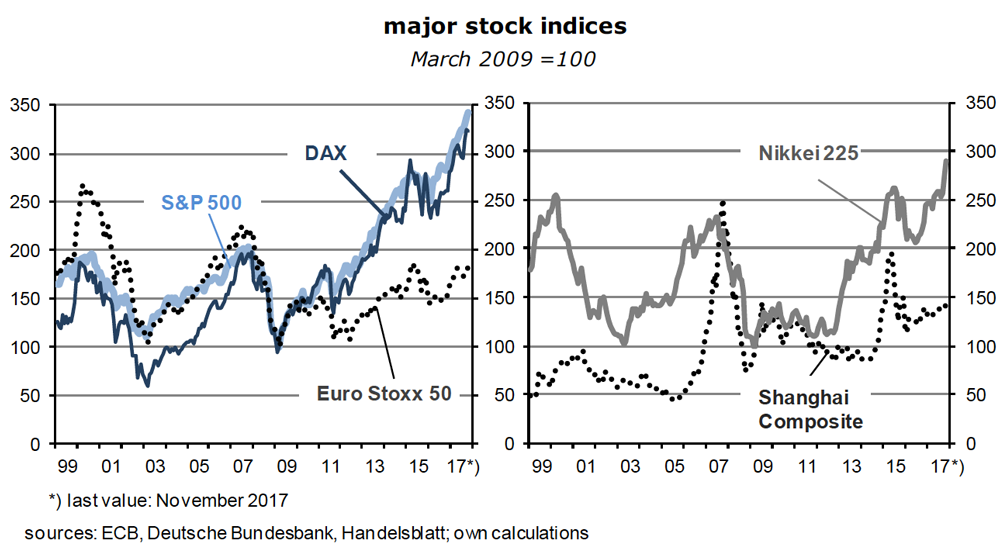

- Seasoned investors are aware that large corrections can occur at the best of times. Germans may remember April 10, 2015 when the DAX hit a high of 12,374, followed by a 29 percent decline over the next ten months. There had been no obvious trigger or early warning sign. On the contrary, beginning in March 2015, the ECB had launched a new large-scale bond-buying program which was planned to last until September 2016, or longer. Mario Draghi had announced that massive quantitative easing would continue until inflation had reached its target value in a sustainable way. It was a promise to maintain very low interest rates for a long time. The news could hardly have been better. Yet the stock market tanked – it had become too expensive. Sounds familiar?

Plenty of slack in the world economy

- In its last World Economic Outlook, the IMF predicts that advanced economies’ real GDP will expand by 2.2 and 2.0 percent this year and next. Such growth rates look like the new normal. They have changed very little since 2014. Compared to the 2.5 percent average of 1999-2008, the ten years before the Great Recession, they are modest but at the same time sustainable, it seems. Capacity constraints have not yet come in sight.

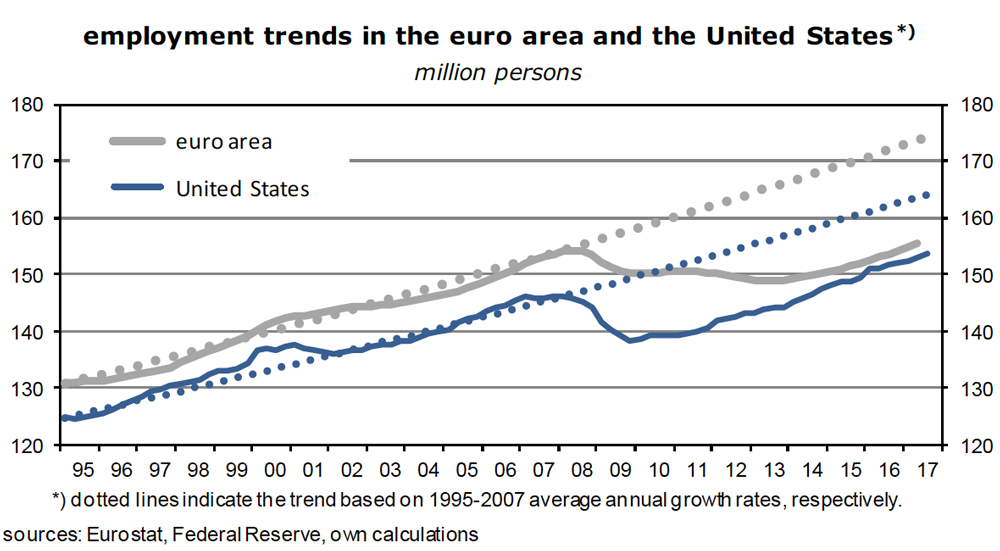

- I don’t buy the standard argument of the European Commission, the IMF or Germany’s research institutes that full employment has already arrived in the OECD region. If you look at the so-called underemployment and labor force participation rates, you’ll notice a lot of slack. This includes the United States. The following graph shows that employment in the two largest economies, the U.S. and the euro area, is, respectively, about 10 and 18 million people below the pre-crisis trend line.

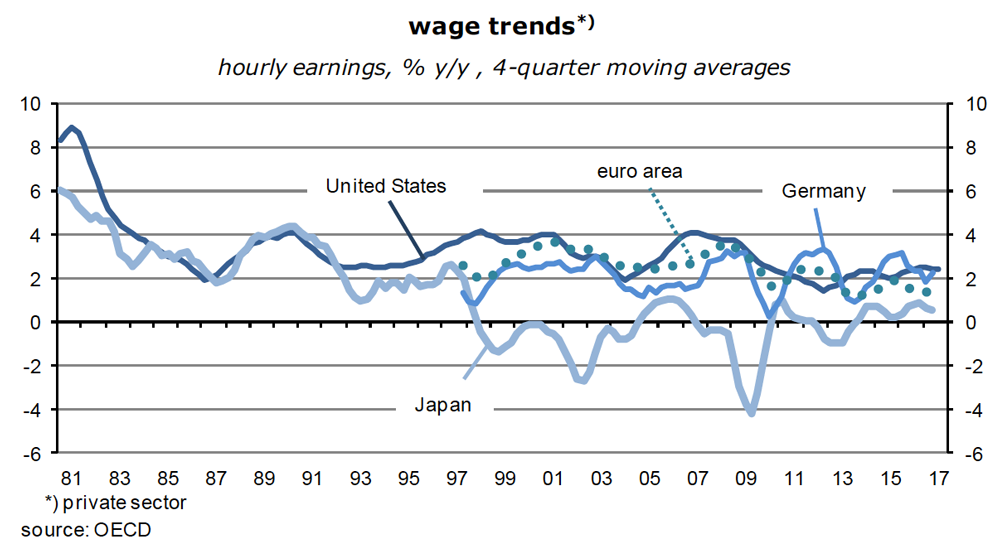

- Below-target inflation is therefore not the enigma it is made out to be: it is simply the result of very low wage inflation – blame globalization, China, weak labor unions and surplus labor in general.

- Emerging and developing economies have also slowed somewhat compared to pre-crisis years – from 6.2 to 4½ percent. Such a moderation of real GDP growth, combined with trend productivity (output per capita) of around 3 percent, suggests that capacity constraints are also no issue yet in this part of the world. Year-after-year, its share of global output rises and now accounts for 58 percent (at purchasing power parities).

- The region is increasingly the driver which, at least for now, holds down world inflation. The difference between 4 ½ percent GDP growth and 3 percent productivity, ie, 1 ½ percent, is a proxy for cost trends there; it is less than the CPI inflation targets of the Fed, the ECB, the Bank of Japan and other central banks in rich countries.

Moderate acceleration of headline inflation

- When will price levels begin to rise significantly faster again? It’s not going to happen in the near term because wage inflation, historically the key determinant of consumer price inflation, remains subdued (see the following graph). Large reserve capacities continue to make it difficult to raise prices (and wages!).

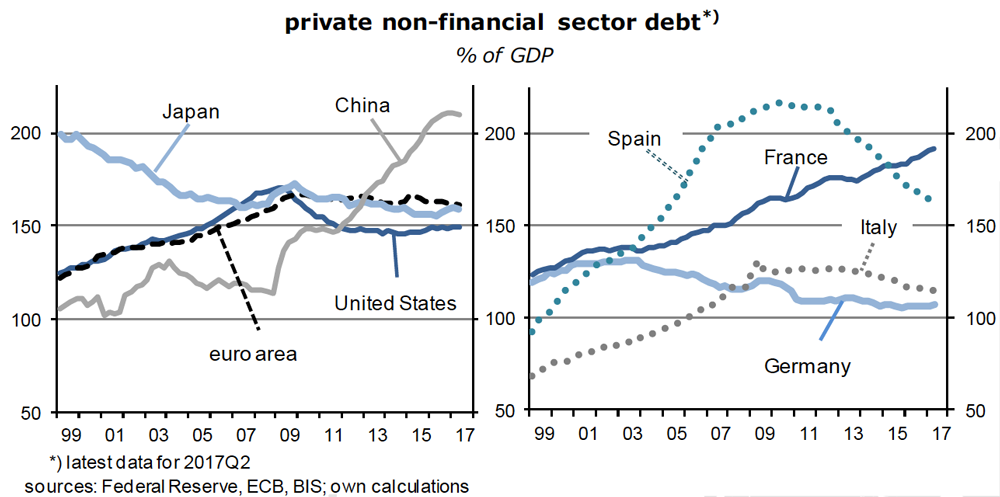

- In addition, don’t underestimate the risk that asset prices may collapse and thus cause another global financial crisis, perhaps another Great Recession. The subsequent deleveraging processes, ie, attempts at debt reduction, could have massive deflationary effects again. As the following graphs show, private sector debt levels remain quite high relative to GDP, especially in China and France. This would not be a problem if asset valuations were not as stretched as they are. To be sure, not each crash or crisis that might happen will happen, but investors are well advised to keep an eye on potential triggers.

- The ECB and the Fed are not yet particularly concerned about such a risk; they point out that bank equity ratios are much higher than before the last crisis and that there are now strong institutional safeguards in place such as the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), bail-in rules for creditors, a tight control of systemically important financial firms by the ECB and much-improved macroprudential supervision.

- For both 2017 and 2018, the IMF expects that consumer price inflation in the advanced countries will accelerate to 1.7 percent, from well below 1 percent in the two previous years. But it will take until 2022 for inflation to finally exceed its speed limit of 2 percent (2.1%). Core inflation remains far below the 2-percent target line.

- For emerging market and developing economies, the IMF forecasts average inflation rates of 4 to 4½ percent in the coming years, well down from the 7½ percent rates of the pre-crisis years. The expectation seems to be that global inflation will converge over time to a rate not much different from 2 percent.

Demographics as a driver of productivity and interest rates

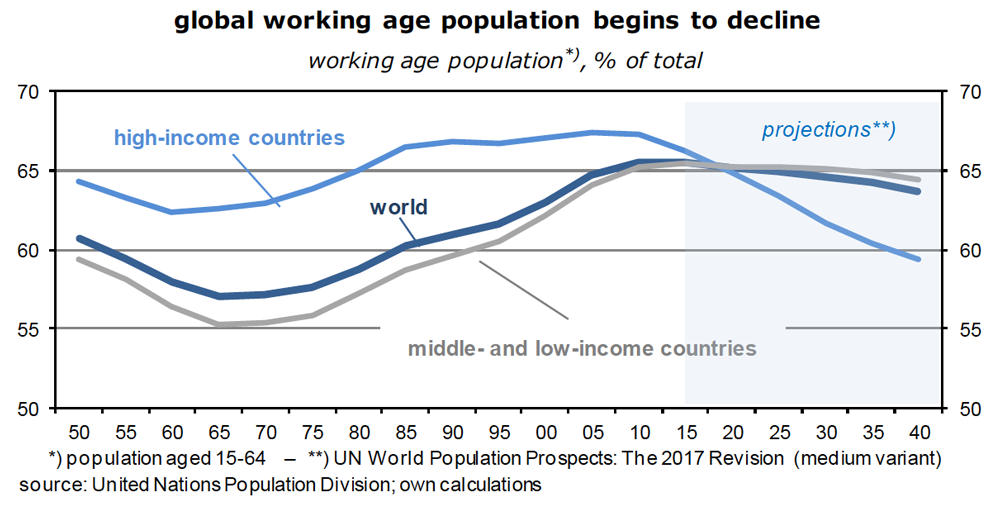

- That inflation will stay subdued as far as the eye can see may prove to be a serious misjudgment. In a recent BIS Working Paper (No 656, August 2017), Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan argue that “Demographics will reverse three multi-decade global trends”. Wages and consumer prices will soon rise significantly faster as the era of abundant and cheap labor draws to a close.

- Between the 1980s and the beginning of this century “the largest ever positive labour supply shock occurred, resulting from demographic trends and from the inclusion of China and eastern Europe into the World Trade Organization.” Simultaneously, women’s and older workers’ labor market participation rates had been taking off. According to data provided by the UN Population Division, the world’s working age population (15-64) expanded by no less than 1.9bn between 1985 and 2015, to 4.8bn, or by 65.5 percent. During this period, world population increased by “only” 51.4 percent, to 7.4bn.

- “This led to a shift in manufacturing to Asia …; a stagnation in real wages; a collapse in the power of private sector trade unions; increasing inequality within countries, ….; deflationary pressures; and falling interest rates.”

- With the exception of Africa, societies are now ageing rapidly. As fertility rates are on a steep downtrend globally, population growth keeps slowing. At the same time the ratio of active to non-active persons shrinks. Raising the retirement age and thus participation rates works in the opposite direction and will be implemented in some western European and Asian countries, but does not change the new trend that ever more old people must be supported by the young and able.

- The result: labor becomes increasingly scarce and expensive. Real wages will rise at a much faster rate than in the past 30 years. This holds for nominal rates as well, given the huge amount of liquidity that has been accumulated in the banking sector. When this happens, a new inflationary cycle will begin.

- Business will respond to rising wage inflation by boosting productivity – the demand for machines and equipment goes up, just as the capital intensity of production. There also won’t be a savings glut anymore. Both inflation and real interest rates will rise, potentially for several decades.

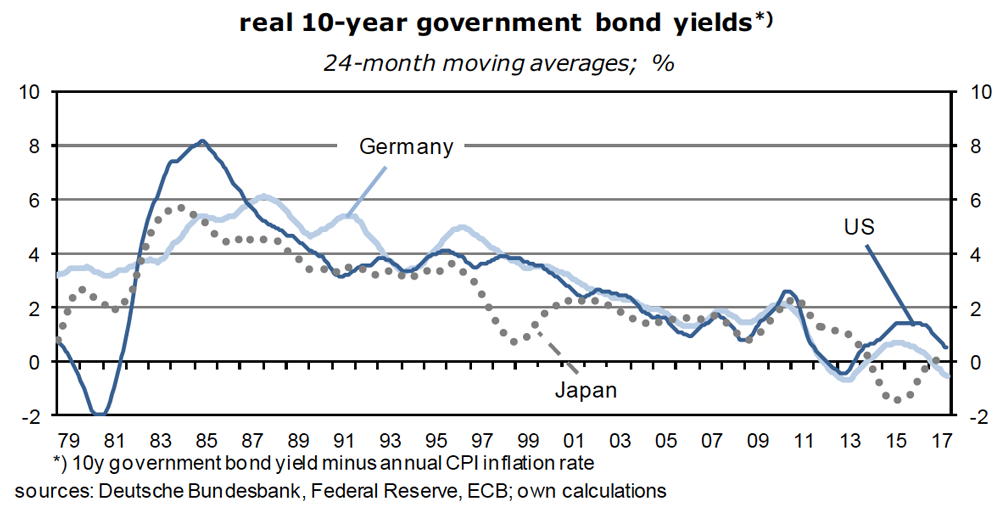

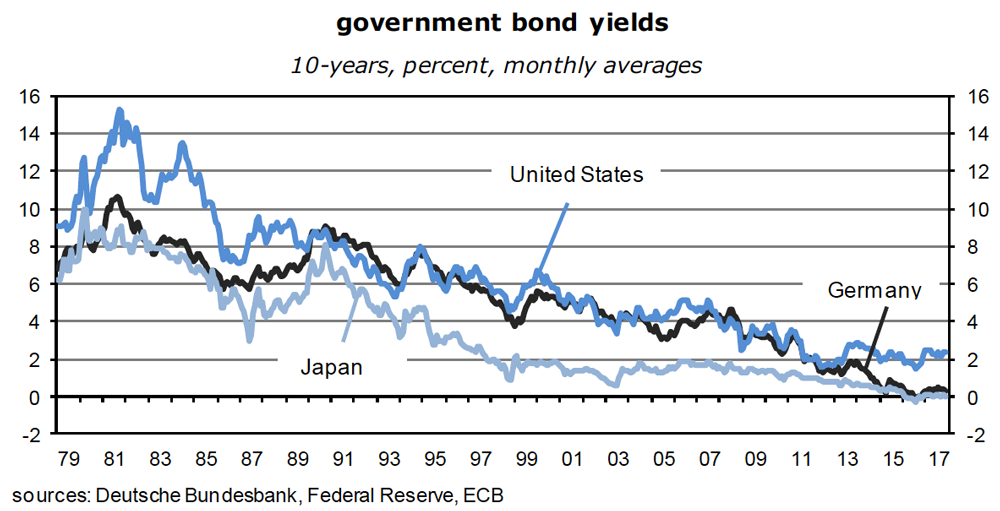

- In other words: the 35-year global trend of falling real and nominal interest rates could have reached a turning point, or is close to it (see the previous and the following graph). Deflation is still a risk, but a smaller one as time goes by. Historically, deflation has been a rare event.

- Investors who have built their reputation and wealth on being mostly long Bunds or Treasuries have to prepare for the new world of insufficient savings, higher inflation rates, steeper productivity trends and rising bond yields. What will happen to stock markets, or real estate, if, in addition, central banks respond by reducing liquidity? They already worry about the huge expansion of their balance sheets since 2008.

- Back to the present. To start with the outlook for equities, today’s valuations suggest that market participants (wishfully) think that profits will rise significantly for several years.

Russian stocks, oil majors and the environment

- The major exception at the moment is Russia where the price-to-earnings ratio on the basis of published earnings stands at just 8.2, which is less than half the ratio in other large markets. The average dividend yield of the firms in the MICEX index is a very generous 4.8% and thus much higher than in advanced economies. Because the rouble has depreciated a lot over the past three years while the oil price has more than doubled since its long-time low in early 2016 (to $63.1), the economy has overcome its recent recession and is now gathering momentum. With consumer price inflation down from about 16 percent just two years ago to 2.7 percent, and the balance on current account in surplus, stability and growth have returned to the Russian economy.

- But its stock market is still a commodity play and thus strongly exposed to the ups and downs of the oil price. Investing in Russia would also be a bet on the further recovery of the rouble exchange rate.

- An alternative energy play for cautious investors would obviously be the cash-rich oil majors of western Europe and the United States. While this would reduce exchange rate risks it does not eliminate the risks associated with the rising competition from alternative energy producers, the rapidly falling costs of electricity from wind and solar, and advances in energy efficiency and storage technology. Add to that that politicians in highly polluted countries are under pressure from the electorate to clean up the environment and forbid certain activities such as driving diesel cars into the city centers.

- Many governments try to internalize externalities, ie, make the polluters pay for the damage they inflict on the environment and the health of people. Burning fossil fuels will increasingly be punished, either via market forces or via regulations and tax policies. Oil prices are also under pressure from the supply side, in response to the shale oil revolution and the defeat of ISIS in Iraq and Syria. In general, bets on the producers and users of fossil fuels do not make much sense anymore.

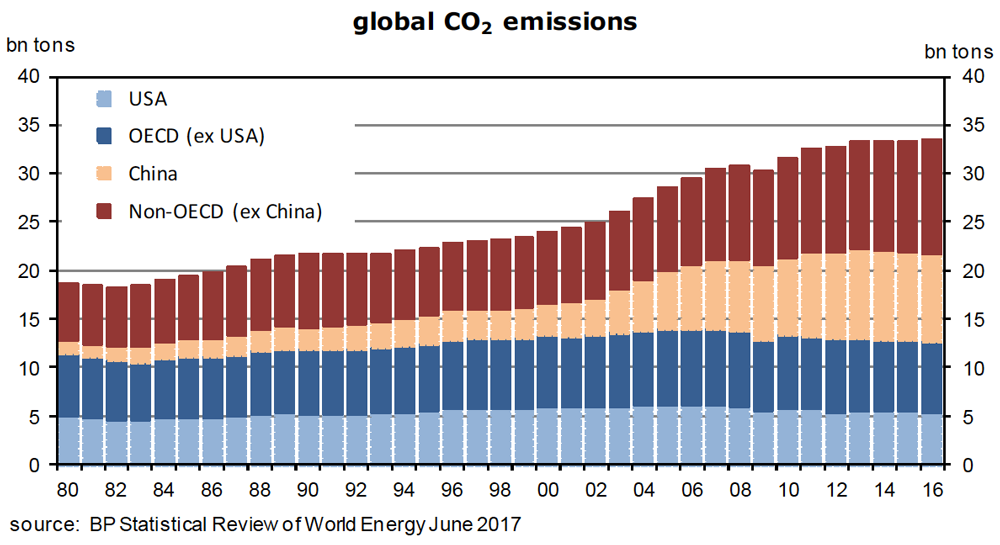

- As the following graph shows, global emissions of the greenhouse gas CO2 are still on the rise which implies that the warming of the earth continues, that the targets set at the Paris climate summit two years ago will probably not be reached and that pollution keeps increasing. As societies get richer, opposition against the deterioration of the environment will get stronger.

The US stock market: this time is different – is it?

- To continue with the analysis of the main stock markets, America’s is not only the world’s biggest, it is also one of the most expensive. Call it the safe haven effect. The price-to-book ratio is a whopping 3.2. After stripping out the highflyers of the information technology sector, which have a weight of around one quarter in the S&P 500, the p/b ratio drops to a more reasonable but still elevated level.

- Here is another yardstick: according to Yale University’s Robert Shiller, the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio (CAPE) of the index stands at an otherworldly 30. The professor argues that, based on his analysis of one and a half centuries of U.S. stock market dynamics, a correction of 20 percent or more will inevitably occur once the CAPE passes 22. The last time this happened was four years ago. Since then investors who like Shiller’s approach have been waiting for a major setback. As it turned out, not only did it not happen, the index has actually gained another 60 percent over those four years!

- Several negatives should make investors skeptical about U.S. stocks:

– the dividend yield is only 1.9%, much less than in European markets,

– the Republicans’ tax plans will drive up government deficits – at 125 percent of GDP, public sector debt is almost as high as Italy’s (132%),

– since the household savings rate is a mere 3.1 percent, the coming of outsized U.S. budget deficits points to a sharp deterioration on the current account and trade fronts; the dollar could get a hit,

– the risk premium, which is the percentage point difference between the earnings yield of the stock market (4.55%) and the real long-term yield of a riskless asset such as the 10-year Treasury (2.40% – 2.0 = 0.4%), is only 4.15 and thus considerably lower than that of stock markets in other advanced countries. It is also low from a historical perspective.

- To be sure, other American fundamentals look quite good. Annualized real GDP growth has recently been in excess of 3 percent, with fixed non-residential investment in the lead. Corporate earnings continue to rise briskly, going by the large difference in third quarter growth rates of producer prices (2.3% y/y) and unit labor costs (-0.1% y/y), as proxies for revenues and costs, in addition to the 1.2 percent y/y increase in manufacturing sector output.

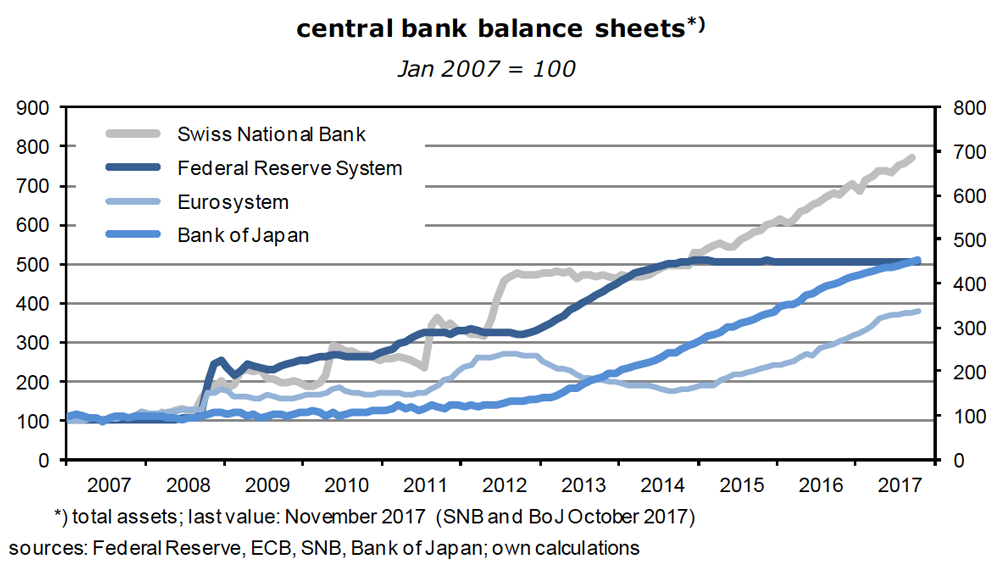

- U.S. monetary policies are tightened only very gradually which also supports the stock market. Back in June 2013, an announcement by Fed chief Ben Bernanke to reduce quantitative easing (“tapering”) in response to robust growth and rising inflation expectations had been a shock (“taper tantrum”) for bond and equity investors and a warning signal that price adjustments in capital and currency markets might easily get out of control when the central bank abruptly changes course. To minimize this risk, the Fed now uses “forward guidance” and treads cautiously. Policy rates are raised only slowly and predictably while the volume of the Fed’s balance sheet is at best reduced at a snail’s pace.

- Since Ms Yellen is not yet convinced that deflation risks have become negligible and also wants to avoid market panics (by providing a “Yellen put”), she, and the FOMC as a whole, accept a serious overvaluation of U.S. stocks. Somehow the Fed is not concerned about asset bubbles and their implications for financial stability. It is extremely hard to take away the punch bowl when the party is in full swing. But bubbles always burst – by definition.

Euroland’s economy is gaining momentum and stability

- The weak euro and the ECB’s implicit promise that policy rates will not be raised before the fourth quarter 2018 is doing wonders for the economy of the euro area. Real GDP has been expanding at annualized rates of 2½ percent in the first three quarters of 2017. This may well continue in 2018. All 18 economies of the currency union are reporting positive growth rates, even Greece and Italy, the two countries that had been hit hardest by the financial and the subsequent euro crises.

- Compared to the United States, unemployment is rather high (at 8.8%), especially among the young (18.6%). Since employment will continue to rise briskly (lately at 1.6% y/y, to about 157m) – as suggested by area-wide surveys –, unemployment rates are bound to decline for several more years by about one percentage point annually. Note that the recovery is fairly young, not yet five years old, because there had been a second recession between Q2 2011 and Q1 2013, after the one of 2008/2009. It should thus have staying power. Only if something unforeseen happens, such as a major stock market correction, or a big appreciation of the euro, might it come to an early halt.

- There is no sign yet that inflation will become a problem. The problem is actually the opposite – below-target inflation. Euro area headline consumer prices were 1.5 percent y/y in November, while the core rate, a leading indicator for the headline rate, continues to fluctuate stubbornly around just 1 percent since the spring of 2013.

- More importantly from the perspective of the ECB, longer-term inflation expectations derived from inflation linkers and forward swaps are between 1.0 and 1.5 percent. Since the compensation per hour worked has been up only 1.6 percent y/y this year so far, unit labor costs exceed their year-ago level by less than 1 percent and thus prevent labor costs from pushing up price levels further down the value chain. No wage inflation, no consumer price inflation!

- After long-lasting austerity policies – which had been one way to align the weaker southern countries with the north, but have contributed to the poor image of the EU among the left-behinds –, the fiscal situation has improved dramatically across the region. Spain and France are doing least well: in terms of public sector deficits as a percentage of 2017 nominal GDP, both are at a little over 3 percent. Since the others have been doing much better, the aggregated government deficit for the region as a whole has probably fallen to merely 1.1 percent.

- The so-called primary balance, which excludes interest payments, is in positive territory in 17 out of 18 member countries (Finland is the exception). It means that debt service is much less of a problem than it used to be. Incidentally, the largest surpluses are registered in Greece (6.9% of GDP) and Italy (2.9%).

- As a result, government bond yields continue to converge. The Italian government, often seen as the most likely candidate to blow up the euro, pays only 1.71% on new 10-year debt, compared to America’s 2.39%. Mario Draghi’s statement of July 2012 that the ECB would do whatever it takes to stabilize the euro looks increasingly credible. Given the central bank’s determination to keep policy rates near zero for at least another year, if not for much longer, the deleveraging processes are likely to continue. Countries become more shock-resistant.

- It has been one of the big surprises that the population in the crisis countries has accepted a lot of economic pain in order to keep the euro. The euro is regarded as an asset worth keeping. Suggestions to leave the common currency had mostly come from xenophobic parties and self-righteous professors in the creditor countries of the north.

- Real long-term bond yields based on inflation expectations remain negative in the key countries of the monetary union, including Germany, the Netherlands, Austria, Finland, Belgium, Ireland, France, Slovenia, the Baltics and Spain (I have ordered the countries according to the level of their nominal yields). It is an indication that investors are quite impressed by the progress made in cleaning up government finances, and the sound fundamentals.

- Investors are less impressed by the growth outlook of the euro area. If the price-to-earnings ratios reflect mainly expectations of future earnings and, perhaps, the exchange rate, I must conclude that American companies will perform significantly better than euro area firms. Investors are willing to pay almost 18 times next year’s estimated earnings for American shares but only 14.8 times earnings for European shares. The S&P 500 contains a larger share of growth companies than the Stoxx Europe 600 price index, something that is also reflected in the differences of dividend yields (1.9% vs. 3.3%) and price-to-book ratios (3.25 vs. 1.92).

- It has been thus for many years. European analysts have always argued that U.S. stocks are overvalued relative to European stocks, but the large valuation gap has never gone away.

- One explanation could be that investors consider European assets as structurally undervalued. When push comes to shove one day and military risks vis-à-vis Russia increase it is better to be in America rather than near the front line. Europe does not have military capabilities in its own right. Politicians are presently discovering this sobering fact.

- Since the European capital market union is still a work in progress, the area lacks the financial fire power in terms of pension funds, corporate bond and private equity markets. It is much easier and more effective to launch new companies in the U.S.

The dollar and the euro

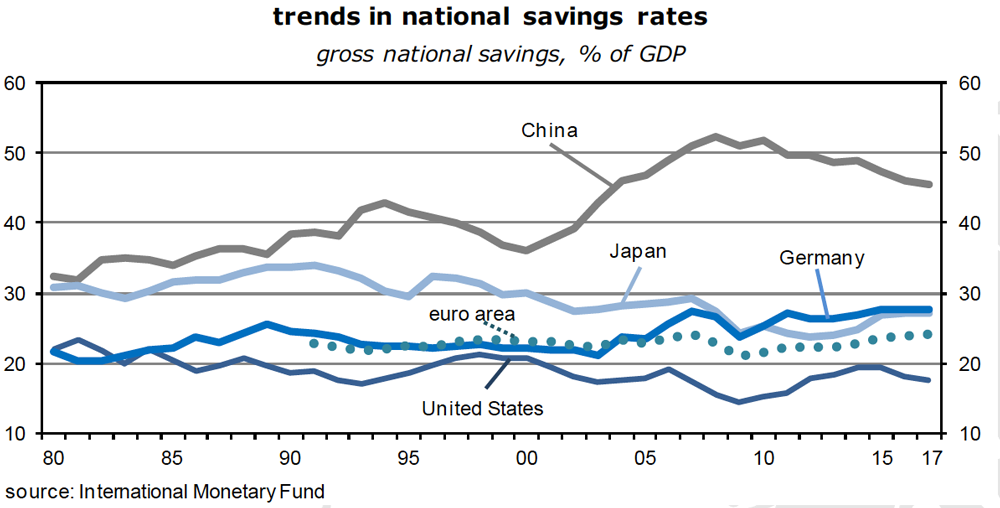

- A final argument that may explain the persistent valuation gap could be exchange rate expectations. While the ECB implicitly holds down the external value of the euro, at least two fundamentals suggest that without such a policy the currency would appreciate a lot: one is the large and increasingly structural surplus in the euro area’s balance on current account, the other the difference in purchasing power parities.

- As the previous graph shows, the “national” savings rate is around 25 percent of GDP. Since the investment ratio is just 22 percent, national accounting identities suggest that the current account surplus must be in the order of 3 percent of GDP. And so it is.

- In euro terms, the surplus will be about 400bn this year, more than three times the Chinese one. There is therefore a strong and steady underlying demand for euros, and, of course, net capital exports of the same order of magnitude. This is the more volatile component. Reversals can come quickly. This is why current account surplus countries tend to have appreciating currencies over the long haul – think Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan or Thailand.

- The situation is almost the exact opposite in Anglophone countries, including India, Canada, Australia, the UK and South Africa, but most importantly in the U.S. There, the low national savings rate leads to a large net inflow of foreign funds which is mirrored in a current account deficit of about 2½ percent of its GDP. In order to attract these inflows, America’s bond, stock and real estate markets must be open and liquid. This they are.

- But the underlying forces still point to a weaker dollar. Without the extremely expansionary policy of the ECB, the euro would long have been at $1.35, or stronger. Both the OECD and the “Economist’s” Big Mac Index arrive at such a purchasing power parity of the euro. For the time being, though, the risk of an appreciation toward such a level is fairly small. The ECB prevents it.

Read the full article in PDF format:

Wermuths_Investment_Outlook_5December2017