DIETER WERMUTH’S INVESTMENT OUTLOOK – AUGUST 2018

Strong headwinds

- Against a generally healthy economic backdrop there is a long list of open issues that have not only the potential to unsettle capital markets. Some of them could even trigger the next global recession. How concerned should investors be about the following?

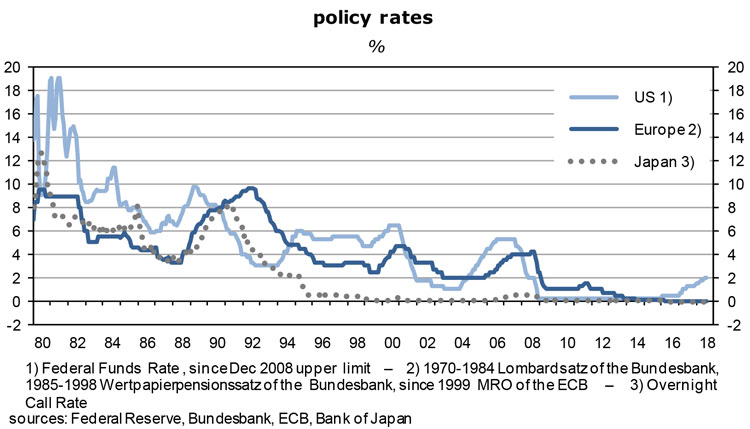

- The Fed seems determined to raise its policy rates two more times this year, and three more times next year – is this the recipe for another emerging markets crisis?

- What will happen if twin-deficit countries such as Turkey, Argentina, Pakistan, and perhaps Brazil and South Africa go over the cliff one day?

- Italy! Should we worry about the 14 percent share of non-performing loans in total loans? What happens if the ECB starts raising rates?

- The trade war launched by Mr Trump against China, Iran, Russia, Turkey and others is hitting business sentiment, incoming orders and capital spending, especially in Europe

- The ECB, the Bank of Japan and the People’s Bank of China intend to stick with zero interest rates – isn’t this distorting exchange rates in a dangerous way?

- Isn’t this also putting at risk the long-term savings plans of households and the business models of life insurers and pension plans?

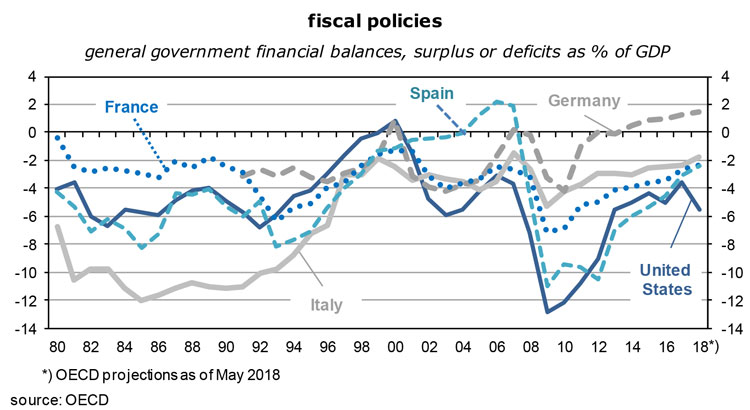

- Why is the US presently expanding so much faster than the euro area, in spite of higher interest rates – have euro area governments unnecessarily overdone fiscal austerity?

- Will imposing sanctions and custom tariffs, in an unpredictable way, against Iran, Turkey, Russia, China, the EU and others depress global capital spending and cause a recession?

- Why are core and wage inflation rates so depressed so late in the business cycle? Are spare capacities larger than generally assumed?

- Why are oil prices so high, in spite of rapidly falling costs of producing electricity from renewables? Could slowing oil supply growth lead to even higher oil prices?

- Given these uncertainties, it is not easy to come up with a consistent and convincing narrative. It will probably be a rocky ride from here on. The best starting point is to look at some key macro indicators. To evaluate the effects of various potential crises, it is necessary to be aware of the situation today.

Some fundamental data

- According to its recent Economic Outlook, the OECD expects the following real GDP growth rates for 2018: 2.9% y/y in the U.S., 2.2% in the euro area, 1.2% in Japan and 6.7% in China. Emerging economies as a group will probably expand by 4.8%, as usual way ahead of the OECD-countries (2.6%). Both of these two numbers are slightly above average growth rates of the past decade. No recession in sight!

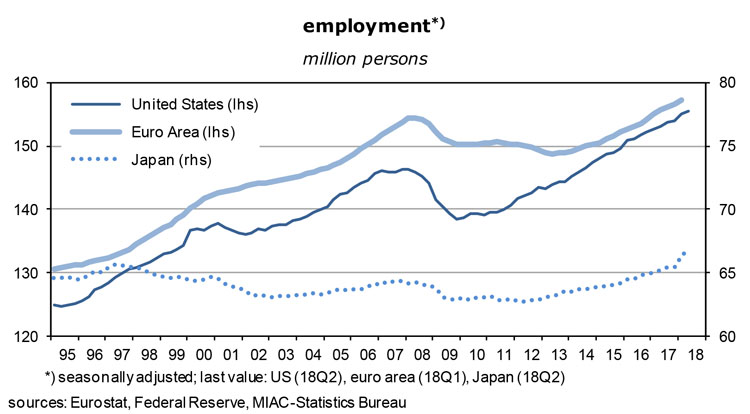

- This is good news for the world’s labor markets. Employment in the U.S.is now 156.0 million, up 1.6% from one year ago. Euro areaemployment has reached 157.2 million, up 1.4% y/y. Even slow-growth Japanexperiences a labor market boom: +1.6% y/y, to 66.3 million. I’d like to know the corresponding numbers for China. I can only make an educated guess, though: employment is probably close to 800 million and may be expanding at an annual rate of 2% (under the assumption that productivity growth on a per-worker basis is almost 5% y/y). There are two and a half times more workers in China than in the U.S. and the euro area combined. Looking at these numbers, is Mr Trump aware that his country urgently needs reliable allies, like the Europeans? In purchasing power parity terms China’s GDP is already significantly larger than America’s (says the IMF).

- As to unemployment rates, they are now around 4% in the U.S. and China, 2.4% in Japan – which looks like full employment – but 8.3% in the euro area. These numbers suggest that expansionary monetary and fiscal policies are still needed in Europe but not necessarily in the other three economies.

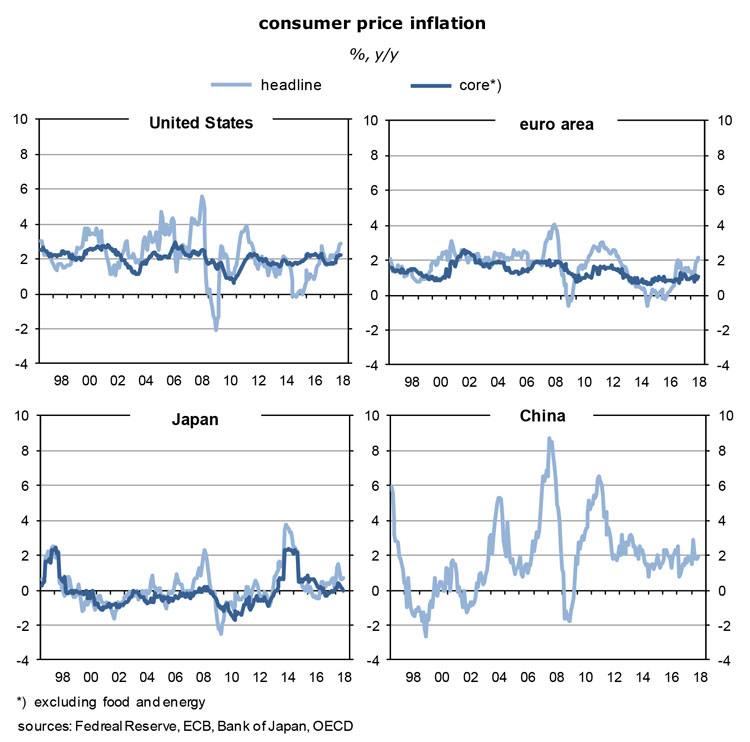

- Global inflation is still quite low, but has begun to accelerate in both the euro area and the U.S.While European headline inflation is now slightly above target, at 2.0% y/y, core inflation remains near its long-term average of 1%. America’s core rate, on the other hand, has already been close to 2% for several months, while the headline rate has reached 2.9%. In the U.S., the fight against deflation has been won, it seems, which allows the Fed to further tighten the reins. Given the four-year lag of its business cycle behind America’s, it is little wonder that this cannot be said about the euro area: underlying inflation is too low.

- Japan has been fighting deflation for almost 30 years by now, but is still not able to declare victory, with the headline rate at only 0.7%. As the next graph shows, there have been two instances of higher rates, but these were caused by tax hikes on consumer purchases. Inflation remains an unattainable dream for both the government and the Bank of Japan. In China, the inflation rate is one of many data puzzles. Why is it only at 1.9%, compared to a 2018 target of 3%, but especially compared to a GDP growth rate of almost 7% and likely productivity growth of 5%? The actual inflation rate should be 6% or so, not 2%.

- According to the OECD, average global consumer price inflation will be 2.2% y/y in 2018. Mainly for two reasons it will remain subdued in coming years: one is the continuing increase in the world’s active labor force, ie, of labor supply. As markets become more integrated across borders, trade war or no trade war, workers in low-wage countries are increasingly competing with those in rich countries – and thus put pressure on their wages. The other reason is excess capacities. They remain large which makes it difficult for firms to raise prices. There is thus no indication of a new wage-price spiral. Going forward, fighting inflation will probably no longer be the main task of economic policies. The emphasis will be more on stimulating long-term growth.

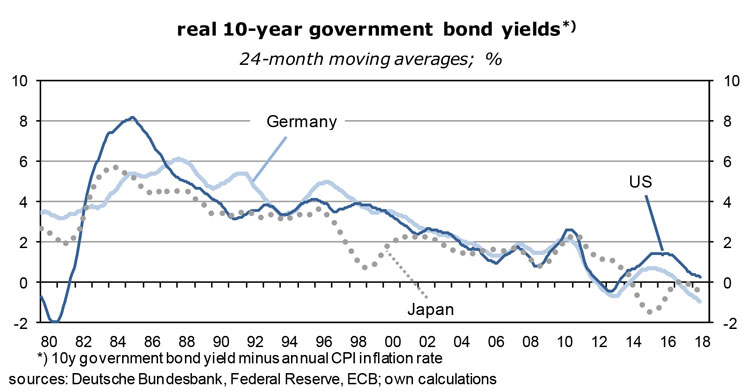

- For bond markets this is a generally positive environment. Except for endangered countries such as Turkey, Argentina, Venezuela, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Egypt or South Africa, all of which have budget as well as current account deficits, there will be no sell-out of bonds. But I would not be surprised if yield spreads were to widen againas investors become more aware of risk as the good times finally taper off.

- Most of the long economic recovery is now probably behind us and the risk of a new recession is therefore increasing.The end of easy monetary policies in the U.S. and, starting in the fall of 2019, in the EU means that borrowing will become more expensive and make saving more attractive. This dampens the demand for goods and services. And not to forget: at some point the global bull market in equities is bound to correct significantly and make many households and firms poorer and force them to put more emphasis on safe-haven assets. Sell Greece, Italy (and the U.S. and the UK?), buy Switzerland, Japan and Germany.

The Fed and the new crisis of emerging economies

- I now turn to some the topics listed in the first paragraph above.

- First, U.S. monetary policies. Since headline inflation rates are now sustainably above the 2 percent target, the Fed has ample room for tighter policies. Near-full employment, a Q2 real GDP growth rate of no less than 4.1% annualized and the deterioration of government finances are supporting arguments for at least five more hikes of the Fed funds rate, to 3.25 – 3.50%, by the fall of next year.Driven by domestic considerations, the U.S. central bank is not concerned about the effects this will have on foreign countries, especially those mentioned in paragraph 9.

- They all have external debt problems. Most of that debt is dollar-denominated and short-term, to a lesser extent also euro-denominated. Rising dollar money market rates are bad enough but it is the large appreciation of the dollar which will really hurt these countries.

- Take the case of Turkey. At the end of Q1 2018 the country’s gross external debt had been $466.7 bn, $270 bn of which was in dollars and €152 bn in euros, plus some smaller exposures in other currencies. In terms of the Turkish lira, the sum of dollar and euro debt had been 2, 056 bn; at today’s exchange rates it has reached 2,718 bn, an increase of about 25%. (A few days ago, at the high point of the crisis, the increase was 80%!) Thousands of Turkish importers and other borrowers of foreign currencies are now close to bankruptcy and forced to ask their lenders for debt relief. Some of these, such as European banks, could also be in trouble.

- In the wake of the depreciation of the lira the country will experience a massive shift of resources from domestic to foreign demand, from imports to exports, which will be a blow to living standards. An IMF-sponsored bail-out would have a similar effect. In the eight years from 2010 to 2017, Turkey’s real GDP had expanded at an average rate of no less than 6.8%, on par with China. But growth had mostly been driven by exports, household consumption, much of it imported, and by feverish construction activity, not so much by investment in machinery and equipment. Foreign debt cannot be serviced from the returns of apartment buildings in Istanbul. The country had increasingly lived beyond its means. Over the past 12 months, the deficit in the balance on current account had reached 5.9% of GDP – Argentina, another sick economy, has a deficit of “only” 4.7%.

- Private lenders to Turkey require very tough terms these days: 10-year government bond yields have shot up to 20%. Since monetary policies have been eased rather than tightened in response to the crisis, market interest rates will rise further. And in the end, the so-called benchmark interest rate of Turkey which stands at 17¾% must go up as well, perhaps by 1,000 basis points to have an impact. Inflation which had been fluctuating around 10% for the past 14 years reached 15.9% y/y in July. It will rise further as import and export prices are exploding – before the inevitable recession brings it down again.

- One rule followed by seasoned investorsis to go short when an asset has experienced an exponential increase of its price. From a Turkish perspective, both the euro and the dollar have become incredibly expensive within a few months. The lira has lost 35% against the dollar this year. Contrarians who dare to act on this rule must now prepare to short euro and dollar and go long Turkish money market assets. It might be a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. Some have obviously already followed such a strategy – within days, the lira has fallen from a low of 7 per dollar to “just” 5.80.

Italy has no problem servicing its debt

- The ECB is obviously concerned about European banks‘ Turkey exposure. In a Bloomberg report last week, Spain’s BBVA, Italy’s UniCredit, Holland’s ING and French BNP Paribas were identified as the banks which are most at risk. The largest by far is BBVA where the equivalent of almost 12% of loans is exposed to Turkey. Investors are also getting nervous. Might there be another euro crisis? The euro continues to lose ground against the dollar, and the yield of 10-y Italian government bonds has once again climbed above that of 10-y Treasuries (3.11% vs. 2.88%), while the German bond market confirms its role as one of the ultimate safe havens (0.31%).

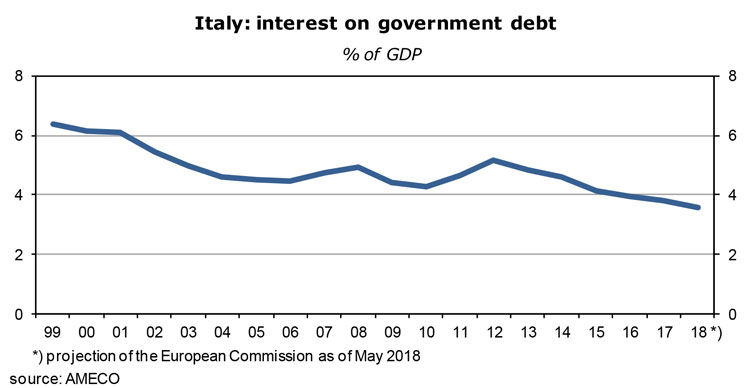

- Turkey may be a big country that is in trouble, but is it big enough to be the trigger of a new euro crisis? Could it bring down Italian banks, then the Italian sovereign – and then the euro? After all, Italy is like Greece times 7. I do not think so.True, Italian government debt is huge – 131% of GDP, or €2,327bn – but it is manageable. The average remaining life of this debt mountain is 7.3 years which means that debt service is not a pressing near-term problem. Moreover, over 20% of the total consists of money market instruments with slightly negative interest rates. For at least one year they will stay negative.

- While Italy remains the largest risk factor in the euro area, it has made considerable progress towards putting its house in order. The country is less risky than it used to be. As the following graph shows, the government budget deficit, as a percentage of GDP, has improved from more than 10% in the eighties to just under an expected 2% in 2018. It now easily meets the Maastricht criterion of 3%. Italy is in a much better position than the U.S. – where the deficit is on the road to 6%. The so-called primary balance (which leaves out interest expenses) continues to be in surplus; in 2017 it had reached 2.2% of GDP.

- Interest payments on public debt have steadily declined since the introduction of the euro in January 1999 – as a share of GDP they dropped from more than 6% to just 3½%. ECB policies are almost a guarantee that this ratio keeps falling for at least another year.

- Many years of austerity policies have pushed down the inflation rate well below the euro average. This so-called internal depreciation has led to a dramatic improvement of Italy’s foreign balances. The current account surplus (!) was almost 3% of GDP last year, following four years of smaller surpluses. In other words, net foreign debt is on the way down which makes Italy less exposed to volatile cross-border capital flows. This is all quite reassuring.

- But what happens if Turkish assets of Italian banks have to be written downin response to the large lira depreciation and, perhaps, a wipe-out of the equity capital of their banking subsidiaries in Turkey? This is a time bomb waiting to explode. It comes on top of Italy’s many unresolved banking problems that existed already before the latest crisis. Discussions with the ECB as the supervisor and the main potential source of funds in a future rescue operation are under way. I wonder whether the contingency plans that are now being drawn up do foresee a full-fledged bail-in of owners, lenders and normal depositors. This had been the plan after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007/2009. Realistically speaking, the system is not yet resilient enough for this approach – which leaves mergers and the nationalization of Italian banks as the most likely way out, as in the past, if write-downs turn out to be too large compared to equity buffers. While this is a sub-optimal solution, it also means that the euro is safe as far as Italian risks are concerned. It may depreciate further but it will be with us for years to come, if not forever.

- Ripple effects from Turkey will also be felt in Spain and France. Add to this that there are several emerging economies other than Turkey which have also been hit hard by the increase of U.S. interest rates and the subsequent depreciation of their exchange rates.Year-to-date, against the dollar, the South African rand is down 14%, the rouble also 14%, the Zloty 8%, the Hungarian forint 9%, the Indian and Indonesian rupees by 9% and 7%, the Argentine peso by 38%, the Brazilian real by 15%, not to speak of Venezuela which is in the grip of hyperinflation and capital flight. Taken together, this is a big chunk of the world economy. China’s yuan is also steadily losing ground against the dollar – but this is not because of external debt problems. On a net basis, China is actually the world’s third largest owner of foreign assets, behind Japan and Germany. Net, it is a lender to the rest of the world, not a borrower.

- Incidentally, another contrarian trade could be to go long European banks. Their Turkey and other emerging market exposure has pushed down the Euro Stoxx Bank Index by more than 20% since its recent high in late January. But the capital positions, returns and profitability of European lenders are in better shape than in similar situation in the last 10 years. Dividend yields are more than 5%.

- Because the Fed will not stop raising rates, it is not unlikely that the present emerging market crisis will escalate further. It is a scary prospect. But it also means that the ECB will stick to its “guidance” that policy rates will not be raised for at least another year. European quality bonds continue to be safe.

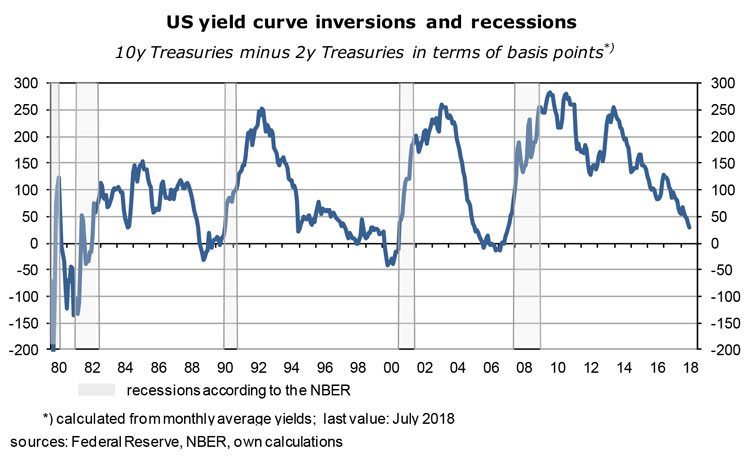

The U.S. is doing well – so far

- How are the chances that the U.S. itself slides into a recession?The expansion is now more than nine years old and already the second longest of the post-war era. Market analysts make much of the fact that the dollar yield curve is on the way to inversion. As the next graph shows, in all instances when the slope had turned negative – when 2-year yields rose above 10-year yields – a recession followed. Luckily, we are not there yet. A U.S. recession would be very bad news for the world economy.

- An inversion can occur in four different ways:in an environment of low but rising policy rates when (1) short rates rise while long rates decline: the central bank hits the brakes while investors think this will bring down inflation and therefore bond yields, or (2) both short and long-term rates rise, but the short end rises faster – this could be the situation in the U.S. today; accelerating inflation allows the central bank to act decisively which brings the economy closer to recession.

- When the yield curve is on a high level, for instance at the outset of a recession, investors might argue that this will (3) lower long interest rates which are partly driven by (receding) inflation expectations whereas the central bank is not yet convinced that it needs to move; finally (4) in a booming economy where inflation is about to get out of control the central bank may decide to keep raising rates – a recession may be seen as the only means to bring inflation down to its target path.

- In other words, the main actor in these scenarios is the central bank. Note that the U.S. government yield curve still has a positive slope of 26 basis points; the inversion has not yet occurred. Note also that there is a variable time lag between the first day of the inversion and the beginning of a recession – in the late eighties, for instance, it had been two years. An American recession has become increasingly likely but it is not imminent.

- I have tried to apply this inversion approach to the Bund market and euro area recessions – it has not worked.Obviously non-interest rate factors (such as the crises in Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Spain) have played an important role in European business cycles. The euro is still a work in progress, and the euro area is a long way from being something like a national economy comparable to the U.S..

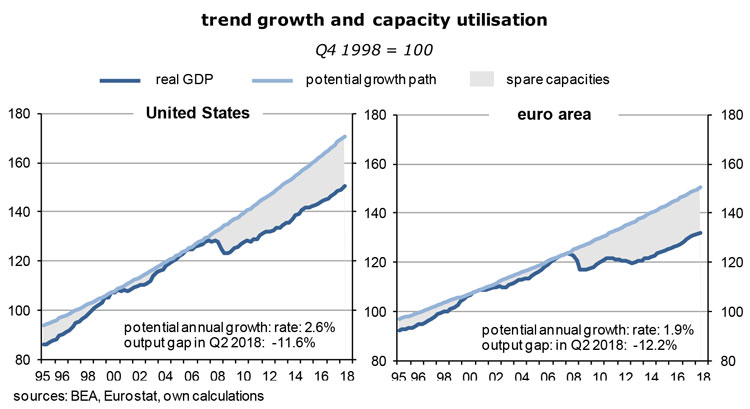

- A recession is often caused by capacity constraints that become apparent after a long expansion. Neither in the U.S. nor in the euro area do I see signs of this, unless I buy the story that for some mysterious reasons productivity growth stopped in 2009 and that all subsequent GDP growth came from rising labor input. Before the Great Crisis, potential GDP grew by 2 – 2½% in the OECD area, but supposedly only by about 1½% afterwards. If this were so, capacity limits would indeed be close, raising the possibility that output growth is limited by the growth rate of potential output, ie, the new 1½% per year rate.

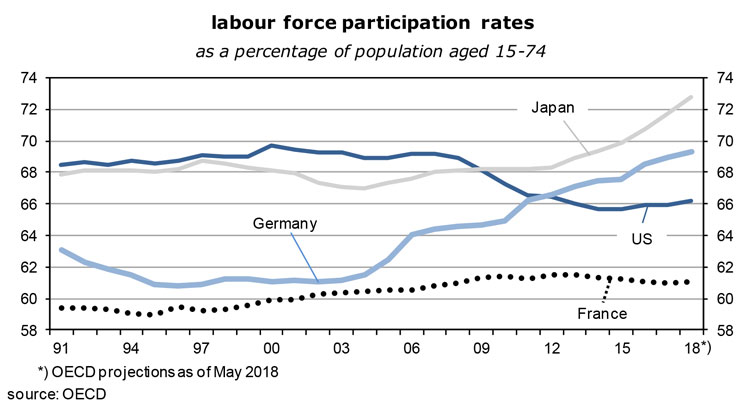

- As the two graphs above suggest there is more than a fighting chance that the expansion will not die because of problems on the supply side.One might argue that the market for qualified labor is exhausted and that there is a lack of employable people. This is certainly not the case in the euro area where recent unemployment and underemployment rates were at 8.3% and 16.4%. Even in the U.S., full employment has not really been achieved yet: between the years before the Great Financial Crisis and today, the country’s labor force participation rate has fallen about three points, from 69 to 66 percent of the 15 to 74 year age cohort. This is the equivalent of almost 5 million people and quite a large “reserve army”.

- If labor markets were really tight, wages would rise much faster than they actually do. No one will be surprised to learn that euro area hourly wages were only +1.9% y/y in Q1, compared to an inflation rate of 1.3%. My estimate for Q3 is that both wage and price inflation are around 2% y/y, ie, zero in real terms. But even in booming America there is no evidence that wages are taking off: in July, average hourly earnings were at 2.7% y/y, less than the 2.9% y/y increase of the consumer price index. Labor market conditions cannot be that tight.

- No, if GDP growth slows, it will be because of problems on the demand side, not on the supply side.This holds for all OECD-countries.

Trade wars are a recipe for recessions

- One candidate for a demand shock is the escalation of the trade warlaunched by the U.S. against the rest of the world. As foreigners begin to retaliate in earnest, American exports will suffer which would then lead to cutbacks in capital expenditures. Since imports into the U.S. have become very cheap in the wake of the strong dollar, they will push aside domestic products and cause problems in import-competing sectors. Other negative effects are predictable: in dollar terms, foreign earnings of U.S. multinationals are worth less than before and cause a hit in P&L statements; inflation rates may well fall again – the U.S. is importing price stability, so to speak; real policy rates will then finally rise which increases the incentive to save on the one hand, and to be more choosy about spending on the other, especially if the Fed sticks to its plan to raise nominal rates five more times. All this could cause a significant slowdown of output growth, perhaps even a recession.

- If things move in this direction, the strategy would beto switch from corporate bonds to Treasuries, to increase the duration of bond portfolios, and to increase the share of defensive stocks at the expense of growth stocks. The 30-year-long U.S. bond market boom would get another lease of life.

- For the euro area, the risks on the demand side are similar to those in the U.S.. An escalating trade war would actually be more of a catastrophe than for the U.S. because international trade plays a much larger role in final demand and business sentiment. Should exports decline, as trade barriers go up, it would be a foregone conclusion that capital spending will be down as well. Domestic demand cannot expand fast enough to fill this gap. Monetary policies may remain expansionary for longer than planned in such a case, but it is hard to imagine how it could generate additional stimulus. On the other hand, this may become the hour of fiscal policies. Not one of euro area countries had a budget deficit in excess of the 3%-Maastricht criterion in Q1, some, like the Netherlands, Germany, Greece (!) and the three Baltics were actually in surplus. In aggregated terms, the euro area deficit is expected to be just 0.7% of GDP in 2018. So there is plenty of room for maneuver. Governments are not under pressure to act at this point, though, because the escalating trade war has not yet left any traces in the hard data.

- In this context, a remark about Italy’s fiscal plans. Market participants are extremely skeptical about their effects on government finances. A sign of this is the yield spread vis-à-vis Germany. In the 10y-range, it has widened from 130 basis points last January to 280 basis points today. Given the precarious state of Italy’s banks and the high level of government debt, they are less than enthusiastic about the coming introduction of a low flat income tax and a citizen’s income for the poorest, the signature policies respectively for the anti-migrant League and Five Star, the two populist partners which run the government. They are afraid that Fitch and Moody’s will downgrade its debt when they review the country in a few weeks: ratings are already just two levels above sub-investment grade.

- I have pointed out above that Italy’s finances are manageable, and I also think that austerity policies should not be continued. Real GDP growth cannot remain at 1% forever. The best would be a combination of easier fiscal policies and measures to boost long-term growth. While the new government may say that it will play hardball with Brussels, in reality it will probably not exceed the budget restrictions by much, if at all. Italy wants to keep the euro. For the time being, investors should therefore wait how the Italian drama unfolds, but they should be aware that this is an opportunity for another contrarian trade.

FX moves will have large effects on the real side of economies

- What will happen to the dollar?The rising Fed Funds rate and the safe haven status of dollar assets in a global crisis will continue to boost its exchange rate. But in the near term America’s balances on trade and current account will deteriorate – the need for net capital imports rises – which in turn requires attractive valuations. At present levels, this can certainly not be said about the dollar nor about the American stock market, especially if a recession looms around the corner.

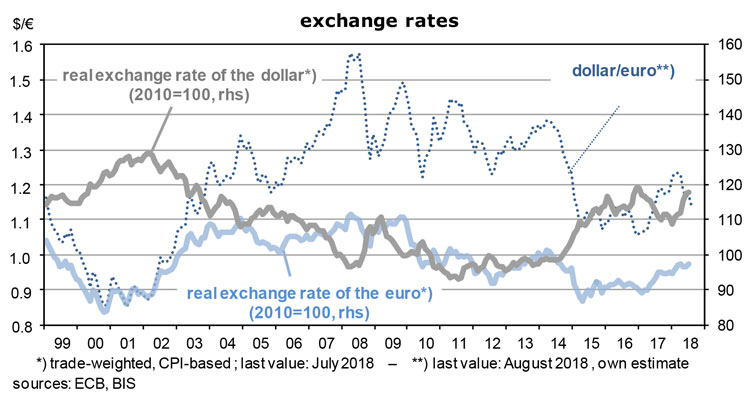

- While the strength of the dollar acts as a brake on U.S. growth, it is like an aphrodisiac for the European economy. The slight real appreciation of the euro in recent months notwithstanding, the international price competitiveness has improved a lot in recent years (see the graph on the next page). Euro area countries are more closely integrated into the world economy than the U.S. which is why the exchange rate of the euro is so important. As it is, the euro is cheap, and so are many euro area assets.There is no need for net capital imports from abroad given the region’s current account surplus which has already reached 3½% of GDP. It is on the road to even higher numbers. The euro area will remain the world’s largest lender.

- The weak euro is an important counterweight to the problems of emerging economies – which are important clients for the region’s firms – and to the coming fall-out from trade wars. It acts like a cushion. Sometimes it is good to have an undervalued currency: it boosts inflation and wages (if these are too low), it helps to create jobs, it raises the value of foreign profits and assets, and it attracts foreign direct and portfolio investments. The flip side is that there is less incentive to invest and increase productivity, ie, potential GDP growth.

- Time to wrap up: for now, markets remain under the spell of the unfolding crises in emerging markets, mainly triggered by the tightening of U.S. monetary policies, and the uncertainties about international trade. In such an environment, the safety of assets will be the main concern of investors. The risk of rising inflation rates is very low – deflation might once again become an issue, depending on the extent of the likely slowdown of global growth.

Some last words

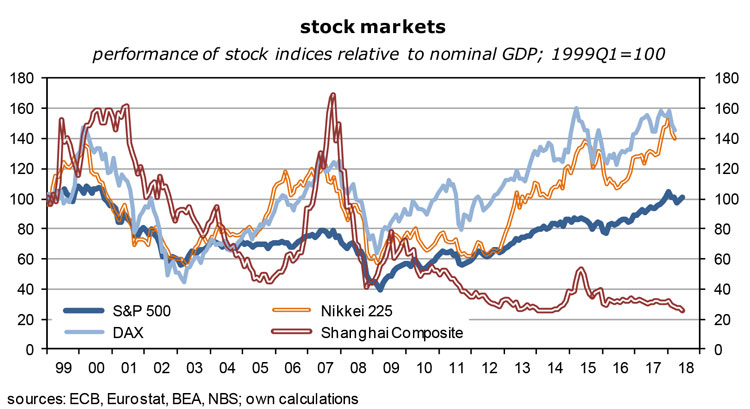

- Finally equities and commodities. The next graph shows that the stock markets of the U.S., Japan and Germany have become quite expensive – indices have risen considerably faster than the nominal GDP of these countries. Any flight to safety should not end up in those stock markets. Investors who have to stay in equities should change the allocation in favor of defensive stocks. China looks cheap, by the way.

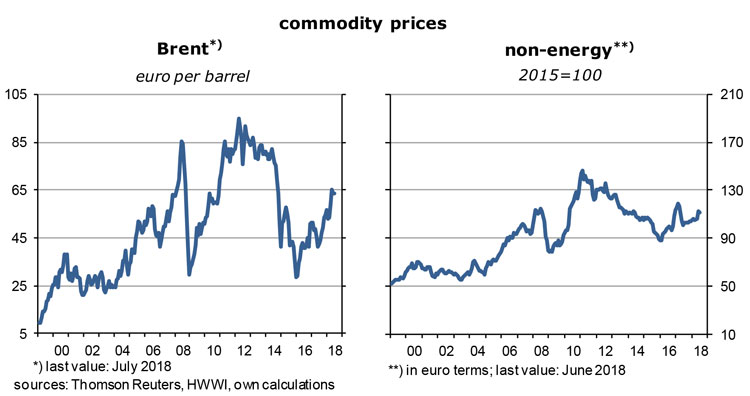

- As to commodities, I would guess that the slowing world economy will lead to falling prices. As the next graph shows, price levels are high, especially compared to those of the nineties, but they are a lot lower than eight years ago, the last cyclical high. It’s a so-so situation. Commodities will not trigger the next global crisis– just the opposite, they are affected by developments outside the reach of their producers.

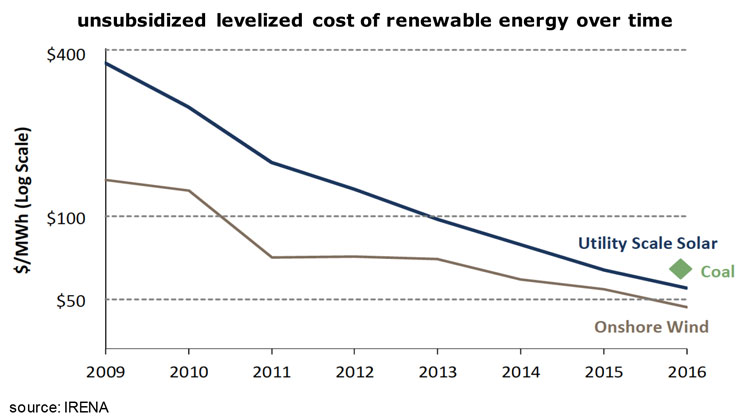

- I am notoriously wrong about the oil price. Let me give it another try then. Global GDP has expanded at average rates of about 3½% in recent years. This was accompanied by 1½% growth rates of oil output (and a further deterioration of the environment). Going forward, the world economy may slow to 2% in, say, two years’ time which may reduce the growth of oil supply to less than 1%. This will depress prices. On the other hand, the green revolution is in full swing. It has led to rapidly and steadily falling electricity costs from solar and wind (see next graph) and to lower storage costs. It will, via arbitrage relationships, reduce prices of fossil fuels, including oil.

- One effect of this has been a significant reduction of oil exploration by the majors. Reserves in the ground are worth less if competing sources of energy are getting cheaper by the day. This means that there are limits to the future supply of oil – which tends to raise its price. Sanctions against Iran and Russia go in the same direction. I also think that the shale oil revolution is about to run its course and supply little additional oil to world markets.

- On balance I would predict a gradual decline of the oil price. There will never again be a global oil crisis.

Read the full article in PDF format:

Wermuths_Investment_Outlook_16August2018