DIETER WERMUTH’S INVESTMENT OUTLOOK – September 2019

Bond markets: look like bubbles, smell like bubbles – are bubbles

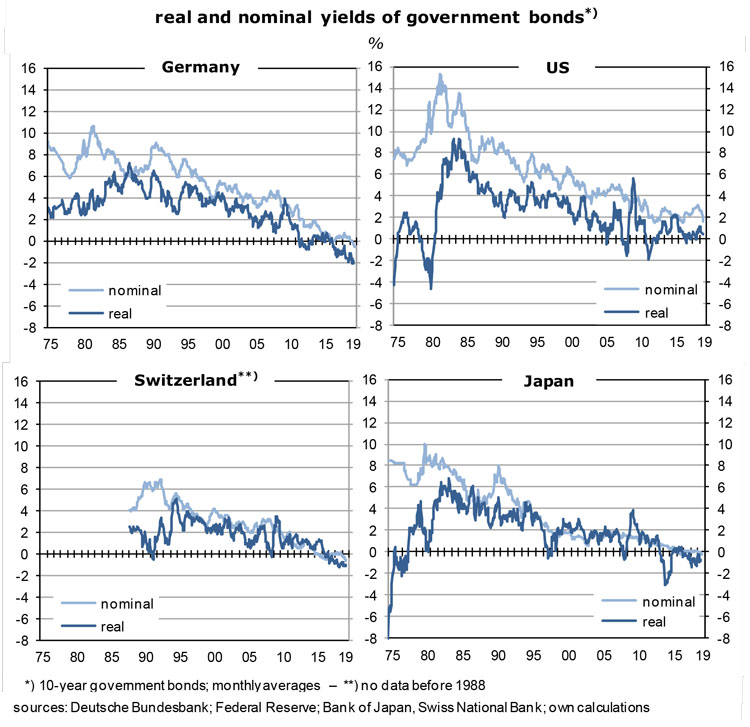

- I am not aware of any economist who has ever predicted that whole yield curves may one day be in negative territory. Yet here we are: interest rates in Japan, France, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland and in eight more countries of the European Monetary Union are preceded by minus signs, from overnight money to 10-year government bonds. Sweden may soon follow Austria in issuing a 100-year bond which will yield close to nothing. This was not supposed to happen, except in case of a long-lasting deflation.

- As I glance through the publications of market analysts, no one seems really surprised about the situation, and hardly anyone expects a major reversal in the foreseeable future: European and Japanese central banks are once again in easing mode and will provide central bank money at negative rates for at least another year. In the U.S., the Fed has reversed course recently and is planning further cuts of the Funds rate. In other words, the funding of bond portfolios is, and will remain, cheap. Equity and real estate portfolios also benefit from easy monetary conditions.

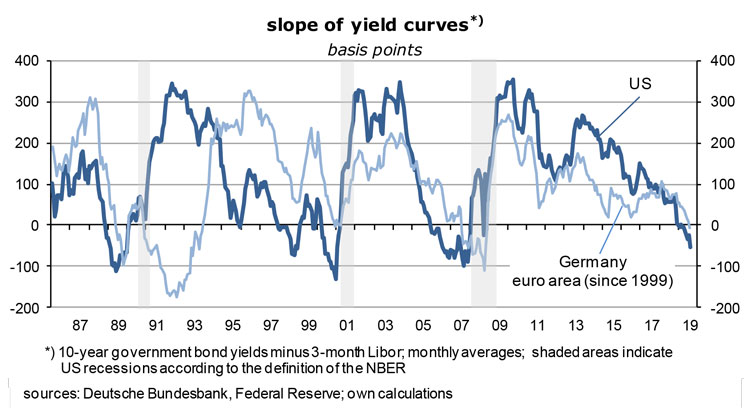

- The bond market rally that began in 1980 could thus continue for a while – but pushes investors ever deeper into uncharted territory. I do not think that the boom in fixed-income securitieswhich is behind the dramatic decline of yield curves is in any way normal. It has the characteristics of a full-blown bubble.In the following I list several observations in support of this view.

fundamentals suggest bonds are hugely overvalued

- Since it is not possible to earn money at negative interest rates using a buy-and-hold strategy, people acquire bonds for the sole reason that they expect their prices to rise further and because they trust that they will find someone to whom they can sell with a profit. Such a strategy (of relying on the last fool) happens in the late stage of a rally and is a sign of a bubble.

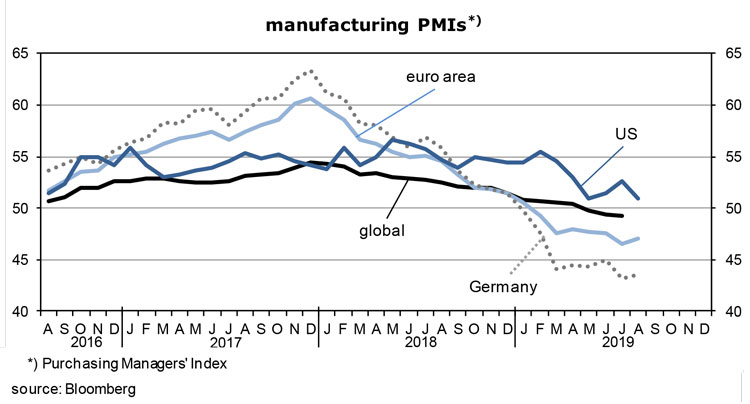

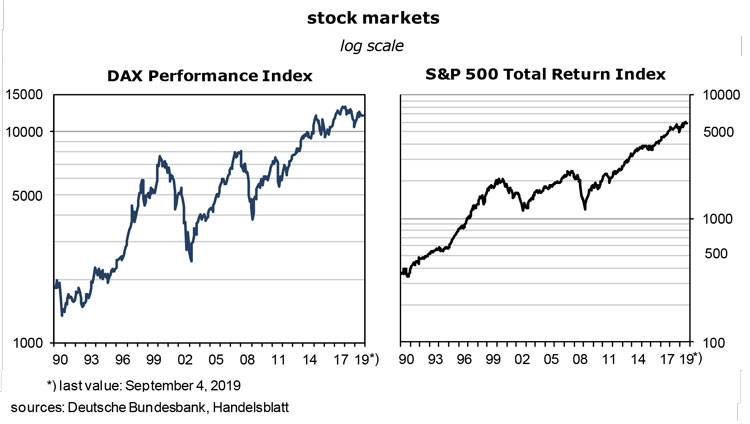

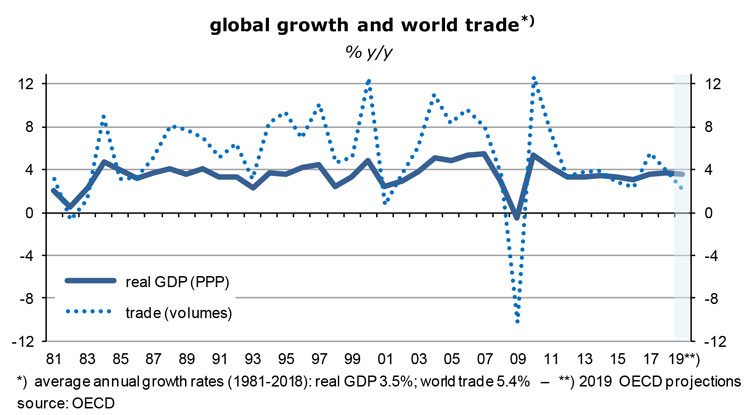

- Even though leading indicators such as manufacturing PMIs (see the following graph) suggest that global economic growth will continue to slow, extremely expensive bonds have led to unrealistically expensive stock markets, often far removed from fundamentals.Equity risk premiums have risen to record highs which persuade contrarian value investors to buy stocks. They do it at their peril, though: when an economy nears stagnation or falls into recession, profits will usually take a hit and cause a steep decline of stock indices, no matter what the situation is on the funding side. We have not seen such a correction yet.

- To take the German example: one would expect that the rapid deterioration of the country’s economic situation and the highly uncertain outlook had resulted in a price-to-earnings ratio not much higher than 10, rather than 20, the market’s present valuation. In July, the volume of new orders to manufacturing was down 5.3% from one year ago while industrial production was -5.7% y/y. In spite of the recession that has probably begun one year ago – and keeps deepening -, investors continue to flock into stock markets because dividend yields are almost 400 basis points higher than yields on 10-year Bunds.

- The only question is the timing of the coming sell-out – on both stock and bond markets.

- Bond yields are normally driven by three factors – the growth rate of productivity, expected inflation and a time premium. They cannot lead a life far removed from these determinants, at least not for long.

- Take Germany again: to start with productivity, as in other rich countries it has slowed in recent years. Over the past decade it was 1.1% per year, but just 0.6% over the last five years. Assume that a rate of 0.8% is about right, the average of the two.

- Next: inflation expectations. One yardstick is the euro area 5year5year inflation swap – it has come down steeply from 1.7% at the beginning of the year to less than 1.3% today. Another indicator is the break-even inflation rate of Italian and German 10-year inflation-protected government bonds (the only two such bonds in the euro area); it is at an average of just 0.6%. A third gauge is the ECB’s survey of professional forecasters – it predicts an inflation rate of 1.6% in the longer term. If I take the average of the three approaches, ie, of 1.3%, 0.6% and 1.6% I get an average of 1.2%. As an aside, the widely varying inflation expectations show how unreliable the predictions are – market participants are not doing better than economists.

- Finally: the time premiumfor holding a bond for ten years. The longer the period, the higher the risk that something unpleasant will happen along the road; the main risk is a significant acceleration of inflation because it would cause bond prices to crash. In the past, when 6% was considered the “normal” 10-year yield, the time premium used to be about 50 basis points – now, in this persistently low-inflation world, something like 20 basis points looks more plausible to me.

- If I multiply trend productivity growth of 0.8%, inflation expectations of 1.2% and the time premium of 0.2 percentage points I get a German “equilibrium” 10-year bond yield of 2.2%.The actual yield is almst 300 basis points less! In the other European countries as well as in Japan the situation is similar. Why the large discrepancy? Why are market yields so much lower than yields derived from fundamentals?

demand and supply of long-term capital

- In an interview last weekend with the FAS, the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, Ewald Nowotny, the former governor of Austria’s central bank and a long-time member of the ECB’s Governing Council, has suggested that the demand for long-term capital may have weakened permanently for a structural reason: modern tech companies, key drivers of the world economy, do not require heavy and voluminous equipment.Coal mines, car factories or steel mills which need lots of physical capital have become less important in today’s services-based advanced economies. This is one reason for the global saving surplus.

- I would add that households and governments are still in deleveraging modein the wake of the 2007 to 2009 financial crisis – they simply do not dare to increase their spending in response to ample liquidity and record-low interest rates. Borrowing is seen as risky which is why the demand for external funds is depressed. At the same time, on the supply side, private as well as institutional savers are risk averse and continue to allocate a large portion of their funds into “safe” government bonds and thus drive up their prices, in spite of very low or even negative nominal yields.

- Negative bond yields could also be a sign that financial investors expect deflation, a long-lasting decline of the general price level. Do they?The three measures of inflation expectation which I have listed above tell a different story – deflation is not imminent. A future inflation rate of 1.2% is low, but it is certainly not deflation. It could actually be the new normal.

- How about the likelihood that the rich countries are heading towards something like the US-depressionof the thirties, ie, a large decline of real GDP and 20-percent unemployment? If market participants would really regard this as realistic and a genuine threat they should not only buy high-grade euro, dollar and yen-denominated bonds but also get rid of equities. A depression is characterized by a big decline in profits, lots of bankruptcies and a stock market rout. But this is not the case.

- Stock markets are doing fine this year, with year-to-date advances mostly in the order of 10 to 25%. The S&P 500 is up 17% so far this year, Germany’s DAX by 15%.

- In euro terms, the strongest markets have been Greece (+39%, as a new conservative government has taken over from Syriza), China (+29%, in spite of the trade woes) and Russia (+27%, reflecting the recovery from recession, high and stable oil prices and a very low average p/e ratio). Investors are generally optimistic about stock markets and thus the economy. For them, the ongoing slow-down of the global economy and world trade will not turn into something catastrophic. Expectations of a looming depression cannot explain why nominal and real bond yields are negative in so many of the rich countries (the main exceptions are the U.S. and the UK).

policy rates have pushed down yield curves – and will keep them in negative territory for some time

- Let me continue on my list of potential determinants for those negative yield curves: central bank policies, ECB policies in particular. In August, harmonized consumer prices in the euro area have been 1.0% y/y while core inflation was at 0.9% y/y, more or less exactly where it has been for the past six years. Headline inflation has fluctuated around this number, and will continue to do so, probably without large deviations. Industrial producer prices excluding construction reflect what is happening in terms of input costs – they are up only 0.2% y/y. Import prices, another important gauge of input costs, are down by about 2% from one year ago (based on German data), in spite of the relentless depreciation of the euro against the dollar. In the wake of a cooling world economy commodity prices have fallen steeply in recent months. Unit labor costs are the main exception from the general picture of very subdued cost inflation – they are up about 2% y/y, as demand for labor has been strong.

- Overall, there are no signs that euro area inflation will accelerate, much to the disappointment of the ECB which aims for a sustainable rate of just under 2%. Now that the effects of a visibly slowing economy begin to kick in, it is increasingly unlikely that the target can be reached in the foreseeable future. At the next policy meeting on September 12 a new round of expansionary measures will therefore be announced,including a cut in the deposit rate which is presently at -0.4%, perhaps a resumption of quantitative easing plus targeted help for banks which suffer from low interest margins and cannot afford to charge their retail depositors negative rates.

- It will not help much. The strategy is basically to double up on policies which have not been successful in the past. The ECB, of course, does not accept such a verdict – board members argue that without the massive flooding of markets with central bank money, or without negative real and nominal policy rates the euro area would be in deflation today. Perhaps, but the truth of the matter is that the ECB does not have a clue how to accelerate inflation.

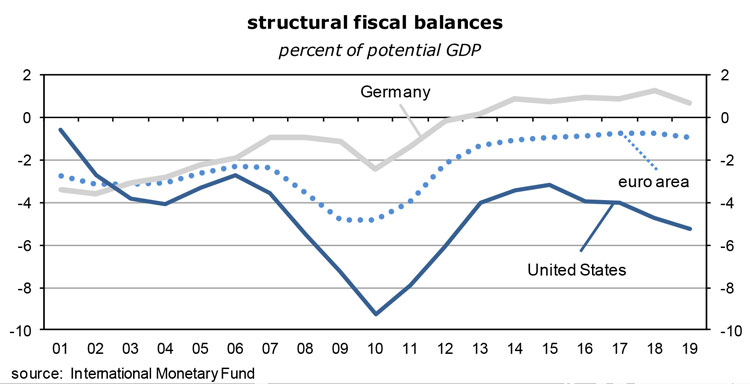

- Mario Draghi continues to argue for more help from the fiscal side: private sector demand is weak, and the only actors who can boost overall demand are governments. Germany, Holland and Austria all have considerable room for maneuver on the fiscal front.

- Their governments see it differently: the structural changes which are now under way cannot be solved by pump-priming the economy.The digital and green revolutions are profoundly altering the production functions in the auto industry, in retail trade, finance and real estate – where the functions of middle men are much reduced -, or the media. World trade patterns are also in flux while exchange rates must find a new equilibrium on their own. One major problem for many European countries that cannot be addressed by easier fiscal policies is the decline of exports of manufactured goods.

- All this will probably cause frictional unemployment and cannot be avoided. Up through the second quarter, domestic demand holds up well, though. Tax cuts and additional government spending, so the argument of the fiscal hardliners, will not improve the situation. What may be needed, apart from the redirection of capital spending, is a depreciation of the euro, and that is happening already.

- Nevertheless, as incoming economic data continue to deteriorate the hard line on fiscal policies in Europe’s surplus countries will gradually be given up. This adds to the expected stimulus of the built-in stabilizers such as slower growth of tax revenues and more spending on social benefits. These will come increasingly into play the more economies lose momentum.

- It is not clear how deep and long the period of sub-potential European GDP growth will be. Since a turning point is nowhere near, the ECB will do whatever it takes to raise the inflation rate – which may take a long time. Investors can therefore rest assured that the cost of funding their securities portfolios will remain depressed. Moreover, they can trust that the ECB will announce a future change of policies with plenty of lead time.

- To sum up: Policy rates are a key determinant, perhaps thekey determinant of sub-zero rates across the entire yield curve.

the effects of quantitative easing and safe haven capital flows

- Another factor that has caused yield curve inversions (where short rates are higher than long ones) and record-low absolute yield levels at the longer end has been quantitative easing policies. By buying government and, to a lesser extent, corporate and mortgage bonds, central banks in Europe, America and Japan have significantly reduced the liquidity of these securities, which in turn has made them scarce commodities and correspondingly expensive.

- In August, the ECB’s balance sheet stood at 40% of the euro area’s GDP; government bond holdings were the equivalent of 18% of GDP. This compares with an average euro area government debt-to-GDP ratio of about 85%. In other words, more than one fifth of the volume of outstanding government debt is held by the central bank and is thus effectively sterilized. In Japan, central bank holdings of JGBs amount to about 90% of GDP.

- In the U.S., the Federal Reserve System’s Treasury bond holdings amount to only about 10% of GDP. Quantitative easing has thus probably lowered government bond yields by less than the activities of the ECB. At close to 2%, American inflation is neither too low nor too high. The Fed’s focus is therefore not the inflation rate these days but the real economy. The following graph suggests that after a very long economic expansion the country is now heading for a recession – if the inversion of the yield curve is once again a reliable predictor.

- In spite of the occasional disagreements the Fed closely cooperates with fiscal policies which are once again unapologetically geared to provide full employment, no matter how large the budget deficits.These will be almost 5% of GDP in 2019 which is in stark contrast to the likely aggregated euro area government deficit of just 1%. The Trump administration likes a new economic movement which maintains that government deficits don’t matter, as long as the borrowing is in the domestic currency.

- In this respect, and judging by the growth and inflation numbers, American economic policies have been very successful,not least, it seems, because of the robust institutional setup. Long-term bond yields of about 1.5% and a policy rate of 2.1% (rather than euroland’s -0.4%) mean that U.S. capital markets are closer to equilibrium than Europe’s or Japan’s. If there is a bond market bubble, it is a relatively small one.

- The massive monetization of government debt in many OECD-countries has not yet led to run-away inflationà la Argentina or Venezuela. It has, however, reduced the cost of debt service – because a major portion of the interest which the government pays on its debt goes to the central bank which then sends it back to the government, ie, to its owner. In German such an operation is called “linke Tasche, rechte Tasche” (left pocket, right pocket). It is money printing without a later hangover, so far at least. The debt held by central banks will effectively never be paid back. Tax payers should appreciate this – but don’t, because they are not aware of this.

- To conclude this section I would say that policy rates are key determinants of nominal and real bond yields while quantitative easing plays a secondary role.

- Yield curves can also reflect cross-border capital flows. Take Switzerland, the classic safe haven country, where yields are lower than anywhere else. 10-year government bonds are at -1.00% while 30 years are at -0.56%. Capital inflows are extremely strong almost all the time which has forced the SNB, the Swiss National Bank, to lower the effective (overnight) policy rate to -0.75%. The main policy target is to keep the exchange rate closely aligned to the euro, the currency of all surrounding countries. In order to preserve the competitiveness of industry and services, currency appreciations should be either prevented or be small. Full employment is a defining feature of the Swiss economy; unemployment is just 2.3%. Low inflation is less of a concern and is also taken more or less for granted – it is presently around 0.5%.

- So the Swiss yield curve lies in negative territory throughout, not because the SNB aims to boost inflation but because it wants to discourage capital inflows and an appreciation of the franc. Since the country has almost no government debt, quantitative easing does not play a role. Could this be a bubble that might burst? Probably not. Super solid policies and sound institutions will continue to attract foreign capital which in turn makes it likely that Swiss interest rates could fall some more and stay negative for a long time.

- But the eleven euro area countries with sub-zero yield curves are a different matter, just as Sweden and Denmark. I am not so sure about Japan which has also become a safe haven country recently. By the criteria I have listed above, the bond markets of the Europeans are seriously overvalued (with the exception of Switzerland). These bubbles will inevitably pop one day.

triggers that may cause bond bubbles to burst

- One obvious trigger would be an increase of the ECB’s deposit or main refinancing rates. Since this is at least one year off, the risk of this happening is quite small. It would invalidate the so-called forward guidance which the ECB regards as an important policy tool. Funding costs will remain where they are – or go down by another notch. Right now, EONIA and the overnight rate are, respectively, 25 to 16 basis points higher than 10-year Bund yields.

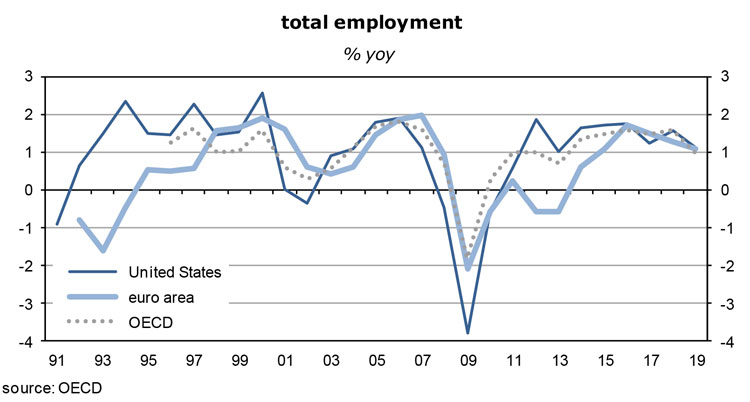

- The statistic to watch is inflation. As I have shown above, investors can still be relaxed. There is no imminent danger. But wage developments have to be monitored closely. Employment growth has been strong for six years now (1.2% p.a.) and unemployment has fallen from 12.1% in mid-2013 to 7.5% now. In Germany and the smaller countries surrounding it there is now de facto full employment – and this will at some point show up in an acceleration of wages.

- There are some ominous signs in Germany. In the second quarter, hourly wages (in the economy as a whole) were up 4.2% y/y and 6.0% q/q annualized. Unit labor costs are rising at similar rates. In industry wages and salaries per working hour have increased at an annualized rate of 4.3% between December and June while unit labor costs were up at an annualized rate of 6.0% between Q4 and Q2 (all based on seasonally adjusted numbers). Wages typically pick up at the late stage of a business cycle. So they behave as expected. Traffic lights are flashing orange by now because wages are an economy’s most important cost component.

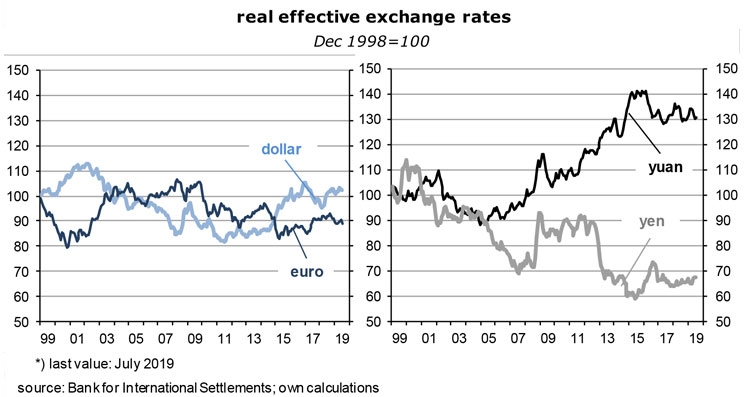

- Another trigger for a turnaround in interest rates could be a depreciation of the euro exchange rate.Gradual declines, as against the dollar in recent years, are ok; after all, import prices have been falling a lot in spite of this weakness. As the next graph shows, in real effective terms the euro has actually been fairly stable – the dollar is just one currency among many that matter for import and export prices.

- Investors might still become nervous should dollar and euro reach parity one day, perhaps because the European economy is hit harder by Brexit than expected.They may have held on to euro area assets because they were convinced that low interest rates and expensive equities would be compensated by an eventual significant appreciation of the euro – not long ago, one euro was worth almost 1.6 dollars! But if this conviction must be revised at some point because Europe does not get its act together after all, a sell-out may follow. I do not see this. In a genuine crisis European policy makers, governments in particular, can draw on their superior creditworthiness. Much larger deficits would not irritate investors who are used to American standards.

- It is also possible that the Fed starts raising ratesbecause the 10-year old expansion and a tight labor market have reduced slack in the U.S. economy so much that inflation finally takes off, pushing up bond yields. So far, things move in the other direction, but they bear watching. Most of the time, the correlation between the bond markets of Germany and America is quite close. This is mainly because institutional investors in fixed income securities and equities want to preserve predetermined allocation ratios: when the dollar value of U.S. bonds falls, the share of European bonds rises which in turn forces investors to reduce their European portfolio – and vice versus.

- The potential losses in the wake of a bond market crash in Europe are huge. Assume, for instance, that the average duration of bond portfolios is seven years and that yields will rise by 300 basis points, ie, to a “normal” level. This reduces the market value of the bond portfolio by 21%. This may be an optimistic view because there will probably be some overshooting. There will be lots of casualties.

Read the full article in PDF format:

Wermuths Investment Outlook September 5, 2019