DIETER WERMUTH’S INVESTMENT OUTLOOK – Mars 2020

Stock market correction will continue

- The coronavirus shock forces investors to change assumptions about market trends. It is not clear how long the epidemic will last. Globally, it may be over in two months, in which case it is best to wait and see and to buy on dips, but if not, they are faced with a totally new game which requires a major reshuffling of assets. To be on the safe side they should seriously consider a bad outcome. What can be done in that case?

- If the epidemic does indeed last longer, such as two more quarters, one obvious conclusion is that economic growth, corporate sales and profits will suffer, perhaps a lot. Output gaps and unemployment will increase, insolvencies will be up significantly, wages will rise less and inflation rates will fall once more. Deflation would be a serious risk again. In such a scenario stock prices would decline steeply, especially those of companies which are highly-leveraged and/or are exposed directly to the coronavirus. High-quality bonds and cash would be the places to be while most of the corporate bond market should be avoided. The flight to safety would be the dominant capital markets narrative.

economic policies become increasingly expansionary

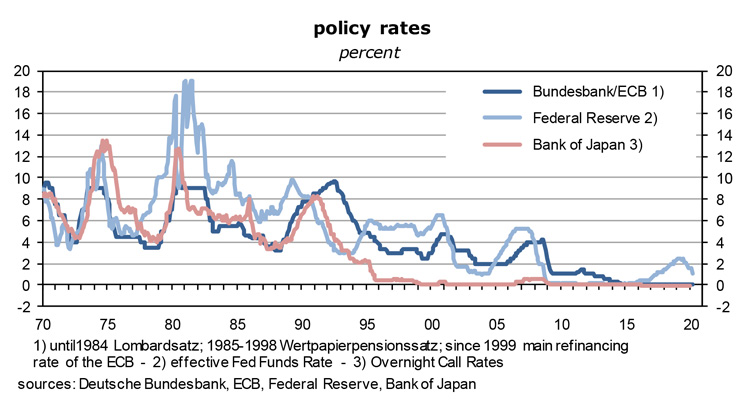

- Expect extremely easy monetary policies: in what looks like a panic reaction, the Fed has cut the upper bound of the Funds rate by 50 basis points to 1.25% last Tuesday. This provides good support for the entire yield curve, not only in the U.S. But not all bonds would benefit. Corporate debt of firms that experience life-threatening hits to their business models will be downgraded while issuers of safe-haven bonds will benefit.

- Central banks are not yet out of ammunition. They could, for instance, monetize a larger chunk of government debt, like in Japan, or increase subsidies for bank lending to the private sector even more, or exempt a larger portion of banks’ central bank deposits from penalty rates, or distribute free cash, ie, helicopter money to all households. But they are effectively close to their operational limits by now.

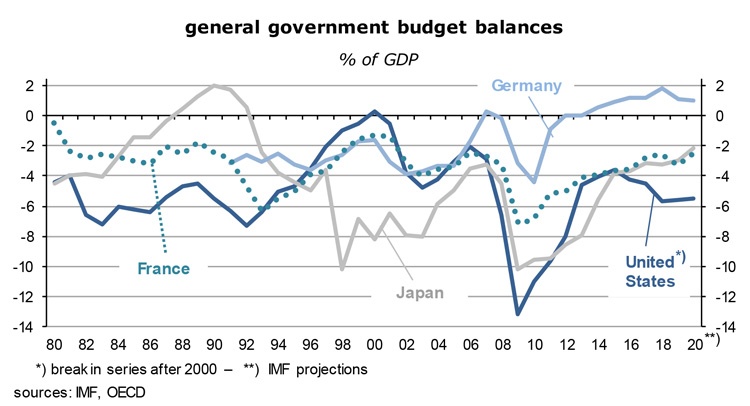

- The strongest stimulus will therefore have to come from lower taxes and more government spending, as in 2008 and 2009. This is a fairly riskless strategy: in almost all OECD-countries, the resulting budget deficits would not increase the interest burden, given that bond yields are either just above zero or negative. Government debt would rise but the additional debt service looks manageable, at least in the next five years or so.

- I would guess that the swing in budget balances needs to exceed 3 percent of GDP if the coming recession is really deep. Even Germany is now preparing a massive fiscal stimulus. As we have seen in Japan, high government debt can go along with negative real and nominal bond yields, a stable price level, even with deflation, as well as a strong exchange rate – provided there are large output gaps.

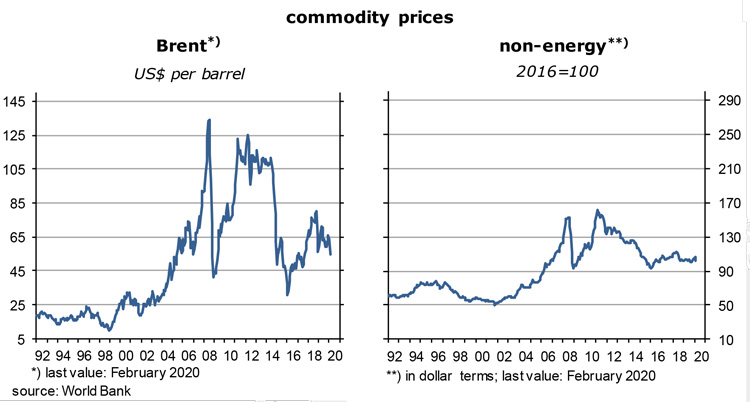

- A defining feature of a recession is weak consumer demand and weak capital spending. As in the past, the prices for oil and gas would react strongly and decline more than proportionally. Brent might end up trading at the 2008 and 2016 market lows of around $30 again – it is at $49.50 now, which is already a 28% decline from its 2020 high in early January. OPEC will cut production quotas but revenues and profits of firms which produce fossil fuels will fall nonetheless.

- The 13% fall of the CRB Commodity Index since the turn of the year would also be just the beginning of a rout. For the countries which are net importers of commodities – most OECD countries are in this group, as well as China -, the ongoing improvement of the so-called terms of trade has the same effects as stimulative monetary and fiscal policies: it boosts the purchasing power of consumers.

stock market sell-out has begun

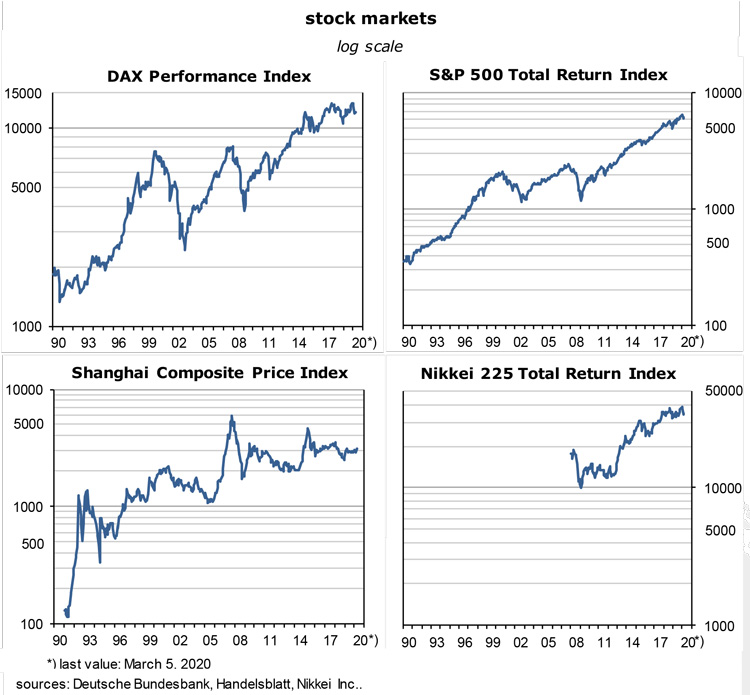

- Compared to previous setbacks, stocks have not yet declined by much. Germany’s DAX index, for example, has lost 22% since January 21, its all-time high. In the five major previous corrections since the turn of the century, losses had been between 23 and 73%. We are getting there*. It is no longer one of the frequent 10 to 15% declines of the past two decades that had always been opportunities to reduce the average purchase prices of portfolios.

- Investors had been surprisingly relaxed until a few days ago. That has changed. Initially they may have been reassured by the fact that global coronavirus infections were rising at weekly rates of “only” 13%, which was considerably less than the weekly doubling of cases in January and early February. The weekly growth rate has now increased to something like 18%. For optimists, there are signs that the epidemic has plateaued in China. They also seem to expect that policy makers have the will and the means to prevent a deep recession. But their case is now rapidly weakening.

- The key to good long-term performance is to buy low. At -22%, investors in German equities are certainly in safer territory than three weeks ago at the peak of the roaring bull market. The quick rebound since February 28, after the first wave of panic selling, is a sign that many had started to seize the opportunity of an oversold stock market to allocate more money to equities. But for several reasons, stock markets in Germany and other large countries may yet have to fall more, perhaps by much more: because of still very rich valuations, the side effects of structural changes in manufacturing, the beginning of a global recession and looming problems in the world’s financial sector. In the U.S., the S&P 500 is down just 11% from its all-time high on February 19; it was down 3.4% yesterday.

large downward revisions of economic growth forecasts

- According to Bloomberg Economics, China, the world’s growth engine, its largest exporter and importer and the origin of the coronavirus epidemic, will grow by just 1.2% this year, after average annual growth rates of about 8% in the previous decade. If Bloomberg is about right, we are talking about a supply shock which will send the rest of the world reeling.

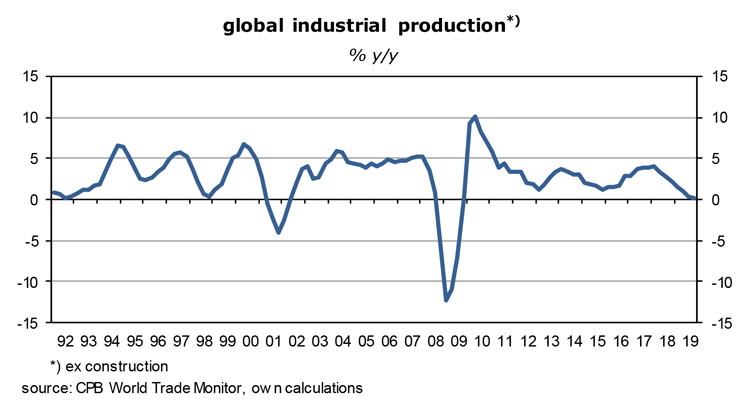

- The OECD has just cut its full-year global growth to 2.4% from 2.9%, the weakest since 2009 when output declined by 0.1% y/y. From 2010 to 2019, the annual average had been 3.7%, with only small variations around the mean.

- The OECD prediction for China’s real GDP growth in 2020 is still a fairly robust 4.9%. The 2019 growth rate had been 6.1%. With car sales in the first two months of this year down by about 80% y/y and the steep decline of electricity production (derived from satellite pictures), the OECD numbers are probably too high – they may reflect the attempt of the organization to prevent self-fulfilling panic reactions. If Bloomberg is right about a Chinese growth rate of only 1.2% – which looks more plausible to me -, this alone will take about 0.8 percentage point from the global GDP growth rate of the OECD. It would then be at 1.6%, rather than 2.4%.

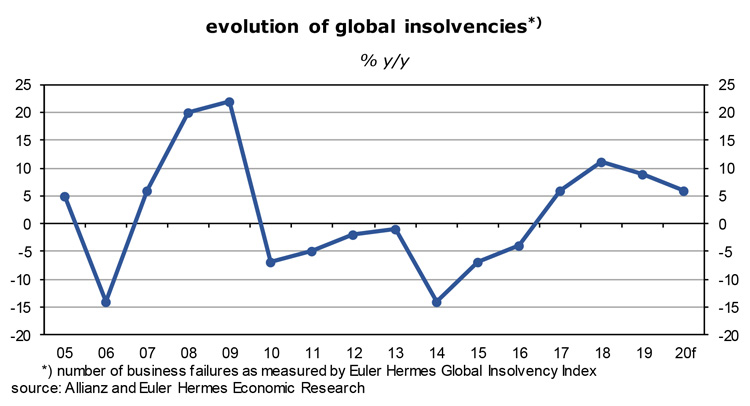

- Since economists consider anything less than 3% to be a recession, the world has now entered one. Profits of firms that are closely integrated into the international division of labor or that are directly affected by the coronavirus will fall, losses and non-performing loans will mount, banks may have to be rescued once more.

- This is a worst-case scenario. Optimists argue that there is a reasonable chance that the epidemic could be over in two or three months as temperatures rise in the northern hemisphere, and then fade from memory as a vigorous catch-up process gets under way. For me, this looks like wishful thinking. While the initial explosive growth of the number of infections is behind us, the disease is not a mostly Chinese phenomenon anymore. South Korea, Iran and Italy are already hit hard, and other countries are following. Investors must make contingency plans.

- By several yardsticks, a doomsday scenario which would hit stock markets hard is not entirely unrealistic. On the basis of today’s elevated (standard) price-to-earnings and price-to-book ratios outside the banking sector, very high cyclically adjusted p/e ratios (CAPE), record-high price-to-sales ratios in the US, and dangerous leverage levels in the corporate sector, stocks may be in for a large decline.

- The OECD has just pointed out that there are “persisting financial vulnerabilities from the tensions between slower growth, high corporate debt and deteriorating credit quality, including in China.” (p. 8 of the March 2 Interim Economic Assessment) Moreover, “just over half of all new investment grade corporate bonds issued in 2019 were rated BBB… in event of a sharp economic downturn … current BBB-rated bonds could be downgraded to non-investment grade, with the associated enforced sales amplifying the financial market effects of the initial downturn triggered by the coronavirus spread.”

- Sectors affected most in the near term are manufacturing industries that rely on long global supply chains, the production of oil, gas and other commodities, international tourism, conferences and trade fairs, airlines, airport operators, aircraft producers, shipping, professional sports, casino operators, hotels, cinema chains, department stores, shopping malls – and banking. There are also some winners, such as pharmaceuticals, hospital chains, internet shopping, home entertainment or tele-conferencing, but their contribution to overall value added is small. The decline of the oil price may boost automakers (or stop the sell-off).

growth had slowed even before the coronavirus

- There had been a crisis in manufacturing even before the present crisis, caused by the trade wars of the United States and excess capacities after the 11-year uninterrupted expansion of the world capital stock. The following graph shows that the global number of bankruptcies, a leading indicator for things to come, had already begun to rise in 2017. With regard to insolvencies, it is like 2007 to 2009 all over again.

- In addition, the shift from fossil fuels to renewables and the concern about the environment in general had begun to trigger major structural changes. These will make redundant large portions of the capital stock – think of coal and nuclear power plants, factories for diesel engines, or fossil fuels in the ground. These would be “stranded”, and thus worthless assets. Structural changes are overdue and cannot be avoided, but the transition from the old to the new comes with potentially heavy frictional costs.

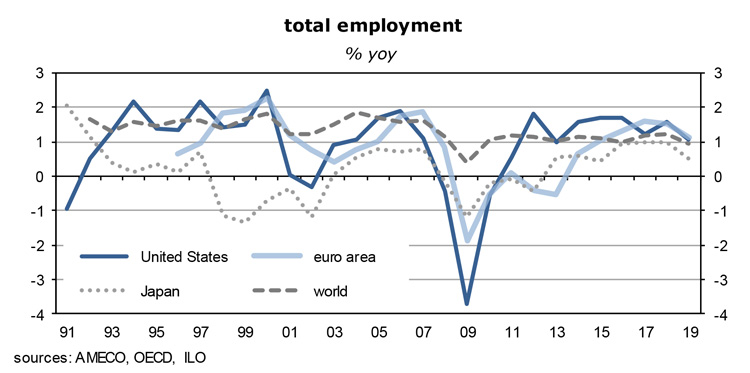

- One surprising element in this rather bleak picture has been the resilience of the labor market. We know that it is a lagging economic indicator and should thus not be surprised too much. Firms have often invested significant amounts of money into the skills of their staff – which they hate to lose in a downswing, especially if there is a chance that it will not last very long. It takes a while for them to realize that the demand for their goods and services has weakened fundamentally (because of structural changes or a recession that lasts longer than expected). In the end, they will have to throw in the towel.

- Such a process seems to be under way now. Over the course of 2020 we will see a deterioration of the world’s employment and unemployment numbers: growth had initially slowed in response to supply shocks, but weak demand will add to the problems from here on.

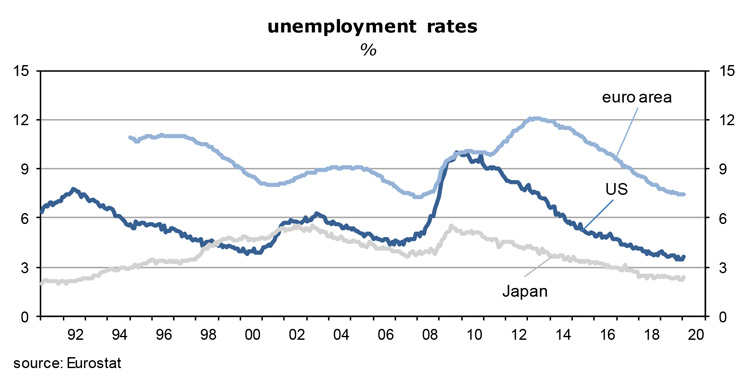

- As the previous graph shows, unemployment in the U.S. and in Japan is still close to all-time lows. In Germany, the jobless rate is just 3.2% (according to the ILO definition), in China it is at 3.6%. For reasons not well understood, productivity growth since the Great Recession has globally been slower than real GDP growth – which is another reason why the demand for labor has slowed so little.

ghost of deflation makes a comeback

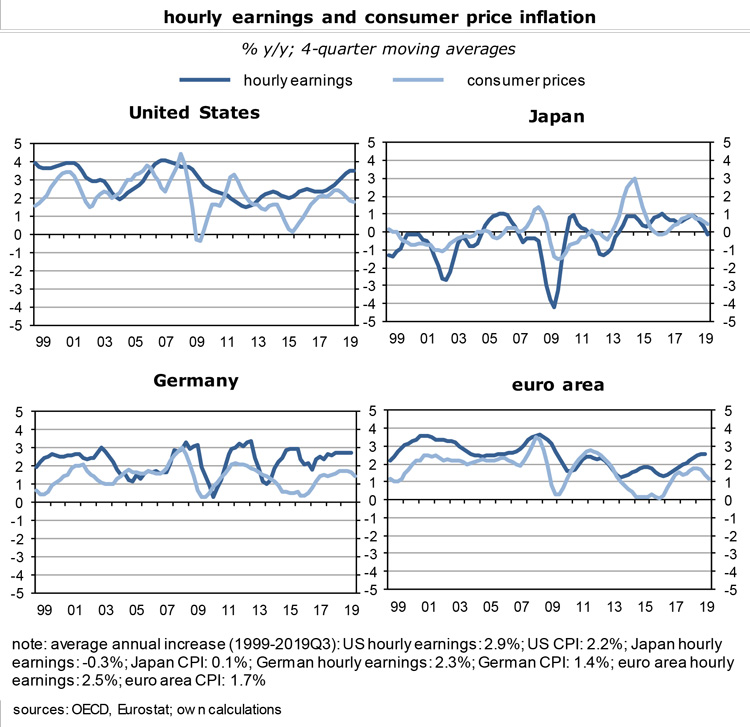

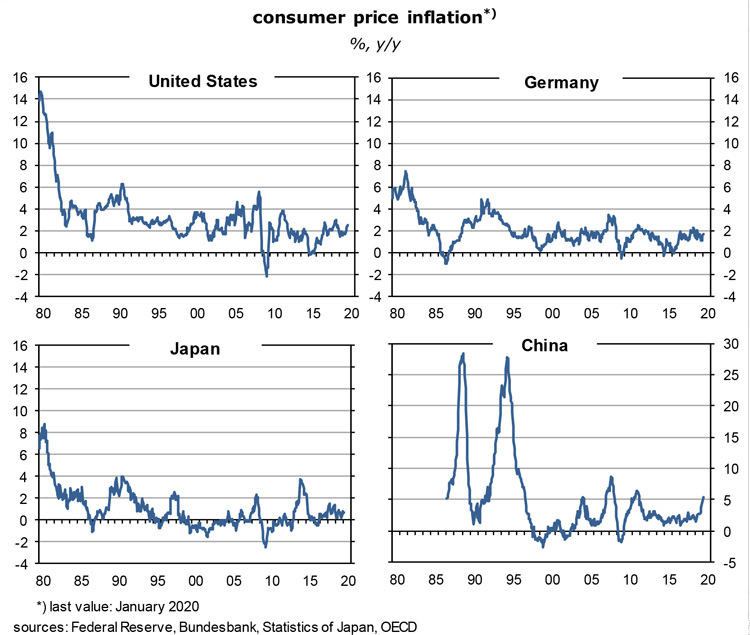

- The previous stock market rallies had been fueled by booming bond markets which in turn reflected easy monetary policies – which in turn reflected persistently low inflation rates. Even before the coronavirus crisis hardly anyone expected inflation to accelerate significantly in the foreseeable future. But we know that danger often looms when everybody is of the same opinion. Is there any chance that inflation will rise rather than fall from here on? As the following graphs show, there had been some signs before the virus epidemic that strong labor markets might finally lead to an acceleration of wage inflation which could then spill over into the general cost structure of the economy.

- This is no longer a plausible scenario. The global recession will put downward pressure on prices and wages.Because output gaps are about to widen a lot, another, perhaps longer-lasting period of deflation may be around the corner.

- In the present environment of weakening demand, there are no convincing arguments that the long-term trend of declining inflation rates that began in the early eighties (in China in the late nineties) will soon come to an end. I could imagine just two extreme scenarios in which inflation would indeed take off again:

- – one would be an abrupt end of the international division of labor, perhaps in reaction to the lessons learned during the coronavirus crisis. Politicians might come under pressure from voters to reduce the supposedly dangerous dependence on foreign products, in particular pharmaceuticals, or IT components. Isolationists would try to close borders not only for migrants but also for a broad range of products that are of strategic importance. This would allow domestic firms to charge higher prices, while wages, protected against competition from foreign workers, would rise faster than before.

- – the other possibility is that monetary and fiscal policies become overly expansionary. Against present expectations it might turn out that the recession will be both short and shallow, in which case the stimulation of demand may have been way too strong. Demand might exceed potential GDP by a significant margin. This, for instance, could be a risk if desperate central bankers and finance ministers decide that the only way out of the recession is helicopter money. This is potentially a good thing, but could get out of controlled if not handled well.

- As I said, these are low-probability events. No reason to sell high-grade bonds or get out of cash as yet.

- The looming global recession is presently the main danger for stock markets, not a tightening of monetary policies in response to rising inflation. The bond market rally is at best a countervailing factor – it increases the risk premium on equities and thus makes them look cheap in relative terms.

- To be sure, capital market participants do not yet expect deflation at this point. Going by the breakeven rates on inflation-protected government bonds, only Japan is a candidate. But even there, longer-term expectation hover closely around the zero mark. In the U.S., 5-year and 10-year inflation expectations are in the order of +1½%. The corresponding numbers for Germany, France and Italy are clustered around half a percent. Investors are not yet afraid of deflation, it seems. They are not overly worried about the effects of the recession. Or they are in a state of denial. Who knows, they may have a point.

Read the full article in PDF format:

Wermuths Investment Outlook March 6, 2020