DIETER WERMUTH’S INVESTMENT OUTLOOK – October 2020

Global recession and strong stock markets – it’s not sustainable

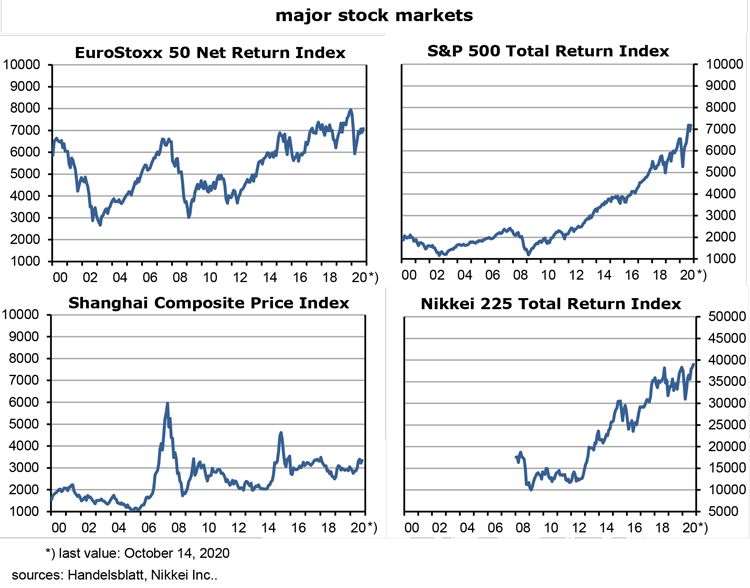

- In mid-October, the main stock markets are up around 35% from their corona crisis lows in March (EuroStoxx 600, CAC 40, Swiss markets, and China’s CSI 300). Others have gained more than 40% (Nikkei, S&P 500, DAX and NASDAQ). In spite of the slight setbacks of recent weeks, investors remain quite euphoric, going by these numbers. Most markets are also near their all-time highs. Price-to-earnings ratios based on corporate results that have already been published are extremely high but even forward-looking ratios, while considerably lower, are still very rich compared to their historical standards.

- Financial investors seem to expect that productivity and profits will rise very strongly from here on as economies close their output gaps again. This is usually the case after a recession, especially a deep one like the present. They also bet on the end of the global pandemic that had triggered the recession.

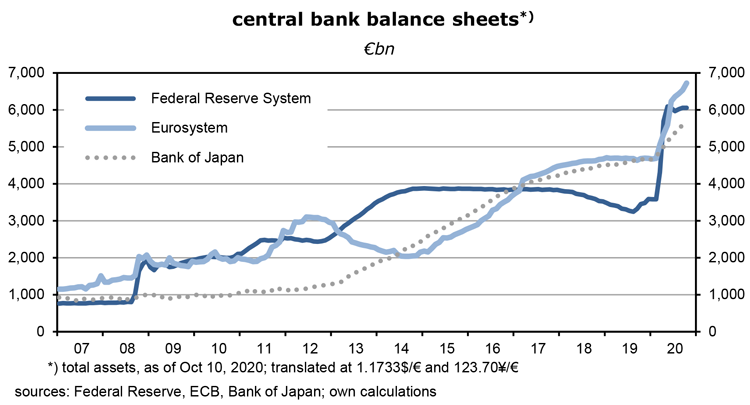

- Monetary and fiscal policy makers have pulled all stops to stimulate the demand for goods and services. Huge amounts of central bank money are pumped into banks at zero interest rates or below, while governments have given up all restraints about budget deficits. Since inflation is below target almost everywhere and shows no signs of accelerating, public opinion is on their side.

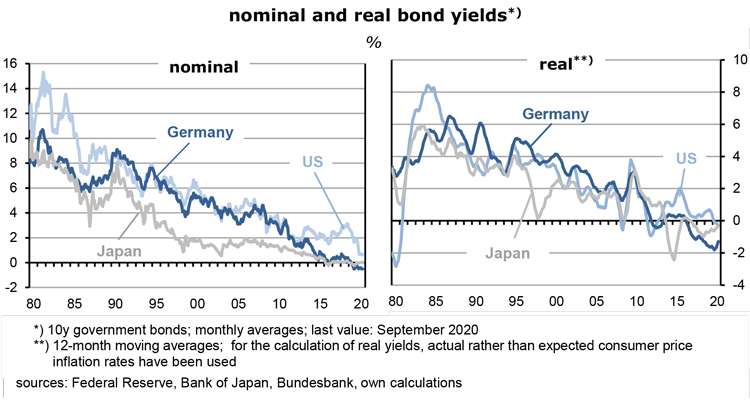

- An additional reason for the strength of stock markets is the fact that fixed-income securities are very expensive, given their record-low yields. Average dividend yields mostly exceed bond yields by significant margins. For many investors, bonds are thus not a viable liquid alternative any longer. Yields of high-quality bonds, even of lower-quality bonds, are near zero: they do not generate any income, and they face the considerable risk of major price declines should inflation take off again one day. In real terms, about $35tr of bonds yield less than zero. If ever there was a global savings glut, it is today.

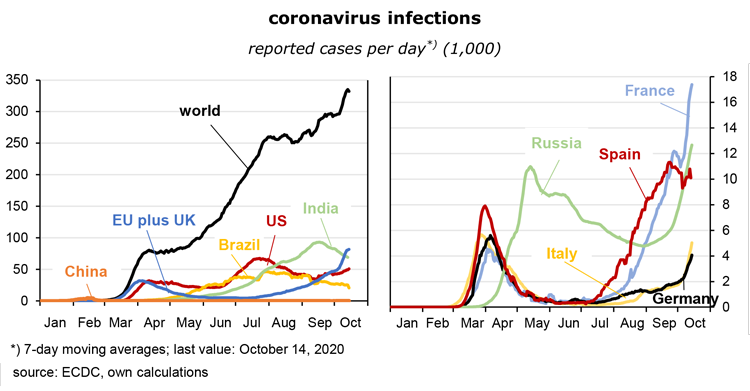

- The most important near-term explanation for the extraordinary strength of asset markets is that investors are betting that the COVID-19 pandemic does not pose a threat anymore. This looks increasingly like wishful thinking, though. The number of global daily infections had peaked in April, then declined a lot during the summer, but is now rising with a vengeance all across Europe and in the Americas. It is about to reach 350,000 per day – and far exceeds its previous high. Some sectors, like tech or health care, do quite well, but on average, economies are visibly losing momentum again. As lockdowns spread, the risk of bankruptcies is rising steeply again.

- The nice days of summer are over and the much-feared second wave of the pandemic has arrived. Recent forecasts of economic growth are probably too optimistic and must be revised down as the global health crisis does not go away. The main exceptions in this bleak assessment are China, Japan and South Korea, but even these countries cannot really do well as long as the rest of the world economy does not.

profits under pressure

- Most large economies operate well below potential GDP. The gaps between actual and potential (trend) GDP are presently in the order of 15% (see my Investment Outlook of June 26, 2020). Never since the depression of the 1930s has output fallen so much. Since labor markets have been quite resilient until recently, reflecting expectations of employers of a quick and robust economic recovery as well as supportive government policies, it is clear that profits have taken a severe hit, certainly on average.

- Unit labor costs, the best indicator for total corporate costs, are up by about 10 percent in most OECD countries compared to the fourth quarter of 2019 while producer prices, a proxy for revenues, are mostly down. The latest PPI numbers are -0.2% y/y for the US, -2.0% for China, ‑3.3% for the euro area, and -0.5% for Japan; two years ago, the year-on-year rates were all positive: 3.0%, 4.1%, 4.2% and 3.1%, respectively. The tide has turned dramatically.

- Deflation prevails in the upper reaches of the global supply chain. When underemployment of resources is high, price wars are the rule. Steeply rising costs and falling revenues mean large corporate losses. That’s where we are today.

GDP forecasts have been revised up recently – probably prematurely

- So the main question is whether all this optimism about future profits makes sense. It mostly depends on the probability of an end to the corona crisis. Until very recently, the consensus seems to have been that this will happen by next spring as one of the several vaccines that are under development in China, Europe and the US will prove effective.

- This is the most important assumption. If true, borrowing and spending would increase steeply, sending the wheels spinning again. Household savings rates are very high as big-ticket expenses for holidays, eating-out and entertainment generally had been significantly curtailed during corona. Business, on the other hand, has reduced capital expenditures, given the uncertainty about the strength of demand for their products. As a result, there is no lack of liquidity or unused credit lines. And interest rates are as low as never before in living memory.

- In other words, if corona is defeated and confidence returns to consumers and entrepreneurs there would probably be a firework of demand for goods and services, previously repressed during the crisis, large productivity gains made possible by lots of underutilized capacities, and a strong increase of employment. Inflation would stay subdued for several quarters because there is initially no need to raise prices: profits will rise briskly simply because of large productivity gains and the rising volume of output.

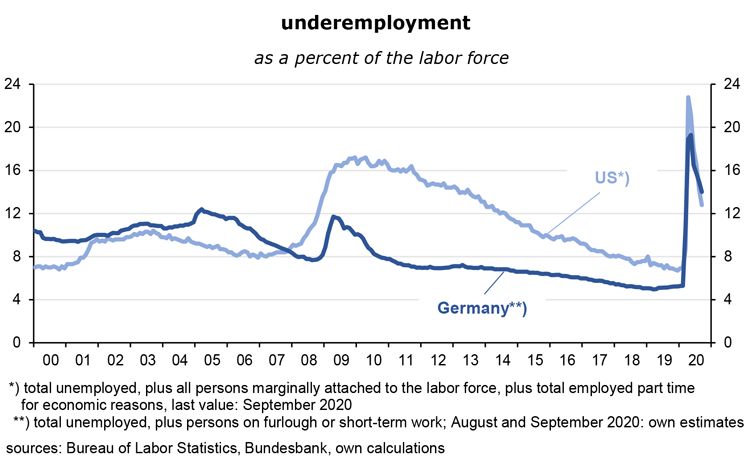

- Wages will increase only moderately as the level of underemployment is likely to remain high for quite some time. In many countries, including Germany and the US, it is in the order of 10 to 15% of the labor force. In other big countries like France, the UK, Italy or Spain, it is even higher. Most workers have realized that their jobs are not as secure as they had assumed and that things could deteriorate quickly. Job security will have top priority going forward. Workers’ negotiating powers are very weak.

- Inflation will thus remain subdued for the foreseeable future and central banks will have no problems making good on their announcements that policy rates will stay close to zero well into the economic recovery, ie, into the year 2022 – or even 2023, as in the United States.

- In such an environment, a sell-out of bonds is quite unlikely. But why does anybody buy bonds these days? Even though they do not generate much income, if at all, their role as hedges in a volatile and potentially overvalued equity portfolio is still important. In a traditional 60% equity / 40% bond portfolio, a 20% stock market correction – which is not a far-fetched idea, given those valuations -, combined with unchanged bond prices reduces the overall loss in the portfolio to 12%. In a stock market panic, when indices are down by, let’s say, 50% it is likely that high-grade bonds will actually gain because there will be a flight to safety. Investors trust that bonds will not default while companies may go bust. In such a scenario, the value of the portfolio would be down 26%, not 50%.

OECD and IMF growth forecasts still too optimistic

- Here is a look at the latest OECD Interim Economic Assessment. It’s called, not surprisingly, “Coronavirus: Living with uncertainty”. In 2020, global real GDP will be 4.5% lower than last year, followed by a 5.0% y/y expansion in 2021. The outlook for 2020 has been raised by 1.5 percentage points since the last forecast four months ago. Still, the recession remains the deepest in living memory. At the end of 2021 the level of output is expected to be still below that of Q4 2019 in most countries, before the pandemic. This implies long-lasting damage to the labor force and the capital stock as skills are lost and machinery and equipment get outdated. In other words, the risk is that trend GDP growth has probably taken a hit. The longer output gaps persist the likelier such an outcome.

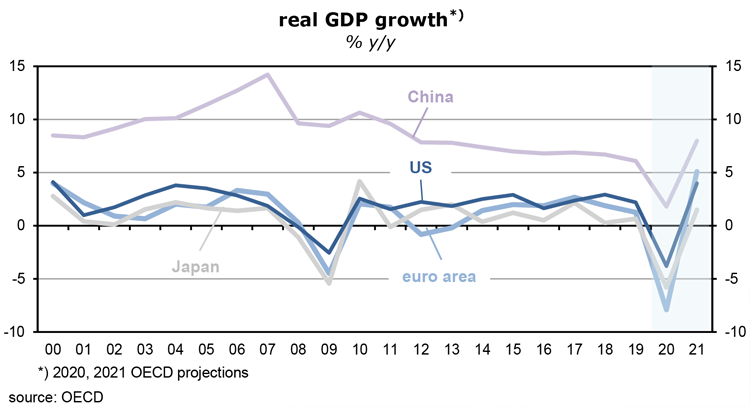

- According to the OECD, considerable differences exist across countries in terms of economic performance. China, the United States and the euro area have surprised on the upside, with real GDP “growth” of +1.8%, -3.8% and -7.9% y/y, respectively, expected in 2020, much better than the initial forecasts, while India, Latin America and South Africa, where the virus continues to rage, will experience double-digit declines.

- The OECD warns that “a stronger resurgence of the virus, or more stringent containment measures could cut 2-3 percentage points from global growth in 2021, with higher unemployment and a prolonged period of weak investment.” Going by the recent strong increase of infections, such a scenario is now the more realistic one. The world’s GDP would then rise by just 2.5% y/y. From today’s perspective, just a couple of weeks after the OECD has published its forecasts, more and more countries are thinking again about new lockdowns and other emergency measures. Germany had been sort of a role model during the Corona crisis but is now struggling desperately to contain the virus.

- In the meantime, the International Monetary Fund has also published its fall report (October 13). Its baseline scenario is very similar to that of the OECD, with global real GDP -4.4% y/y in 2020, followed by +5.2%. As the virus disrupts international supply chains, the volume of global trade falls by no less than 10.4% y/y in 2020 and will not fully recover in 2021.

China and the rest of East Asia have become the world’s growth engines

- The main exception in all this is China. The coronavirus had spread from there, but it had also been tackled early and vigorously. For months, almost no new infections have been reported, and the number of deaths has stabilized at close to zero (if statistics are reliable). India is presently firmly in the lead, with new daily infections in the order of 70,000 and daily fatalities of around 1,000. Number two in the league tables are the United States where the overall number of corona deaths is heading for 220,000 in a couple of days. If the euro area were a country, it would be the worst, with more than 100,000 new infections every day.

- China, together with Japan, South Korea and Taiwan has become the world economy’s growth engine. The OECD forecasts that its real GDP is on track to increase by 8.0% y/y in 2021, after a positive if modest 1.8% growth rate this year. The IMF has very similar, if slightly higher numbers: with 2018 real GDP put at 100, the expectation for 2021 is 116.9 while the US reaches a relatively measly 100.8 over that period, ie, will be more or less back to its 2018 level; at 97.7, poor old Europe is recovering at an even slower rate.

- Using today’s exchange rates, China’s nominal GDP will reach about €14.3tr in 2021 and thus continues to catch up quickly with the US. America’s nominal GDP will be about €18.5tr next year, that of the euro area about €11.5tr, and Japan’s about €4.3tr. In terms of purchasing power parities, as calculated by the IMF, China’s share in global GDP had already been 17.4% in 2019, ahead of the US (15.9%), the euro area (12.5%) and Japan (4.1%). China is also the main player in international trade – in September its imports were no less than +6.0% m/m in volume terms, and +19.2% y/y (according to Capital Economics, calculated from y/y numbers).

- For financial investors with a long-term view, who remain aware of potential new restrictions on capital flows and the risks of a trade war with the United States, Chinese stock markets are the place to be.

major structural changes under way

- As people have been forced by Corona to change their behavior and spending habits, the structure of demand and output is now very different from what it was before. Whether this will be permanent is not yet clear. Much depends on the duration of the pandemic. Near-term, “people-intensive” activities are out and the hits to growth and employment cannot be avoided. There won’t be large sporting or music events anymore, no more going to the movies or eating out in crowded restaurants. People will spend less on flying, holiday cruises and travelling in general. They will also reduce the time spent on commuting to and from work as the home office turns out to be a good idea.

- The new boom in electric and other bicycles and do-it-yourself stores is probably here to stay, just as the gradual demise of cars with internal combustion engines, especially gas-guzzling SUVs (such predictions have a very bad track record, though). Real estate prices in suburbia will continue to rise relative to prices in city centers. The trend of spending a growing share of household income on health care is likely to accelerate as people are scared of the next virus attack. And so on. It’s a long list.

- On the supply side, the digitalization will accelerate. This explains the boom of tech stocks. Online shopping had been a logistic necessity in recent months but people have probably also learned to appreciate it and will continue to buy online. Department stores and shopping malls are doomed. Print media will become less important as most information arrives via the internet. The role of digital devices in education will increase rapidly after these had been so useful during the pandemic. Will this reduce the cost of education? Will students only go to their classrooms because they need social contacts and friends – and to take exams? Many new business models based on the internet will be developed.

fight for a better climate intensifies

- In recent months, one surprise has been the new awareness of the damage inflicted on the environment by our previous lifestyle. There is almost too much hype about green issues these days. “Greenwashing” is in full swing. But there is also something more permanent under way. Over the course of the pandemic, it has turned out that a modest lifestyle is not the same as a low standard of living. Ostentatious consumption is increasingly regarded as somewhat vulgar by many of the young. Who is still impressed by powerful and flashy cars? Or by the latest fashion?

- On the other hand, it is quite scary, at least here in Europe, how one extremely hot and dry summer follows the next. To save nature, it should rain for weeks on end, but doesn’t. The huge forest fires in the Amazon, on the US west coast and in Siberia, the rapid melting of the arctic ice, now regularly in the news, do not fail to impress. In Germany, September was the hottest ever since 1880 when records began to be taken, and the average global temperature so far this year has been 1.3 degrees Celsius higher than in pre-industrial times. The world is heating up quickly. Especially younger people worry a lot about the future of the planet – and many become climate activists.

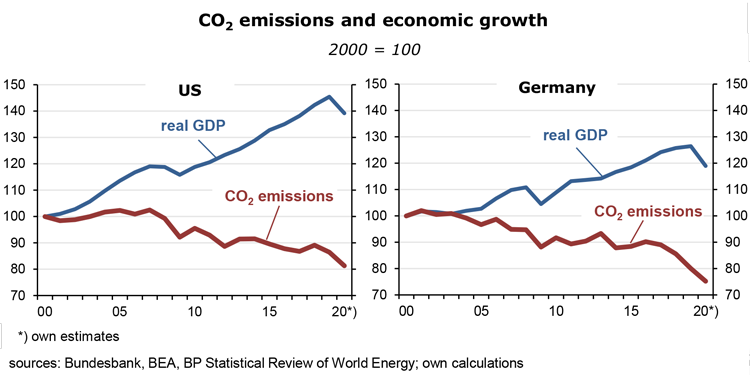

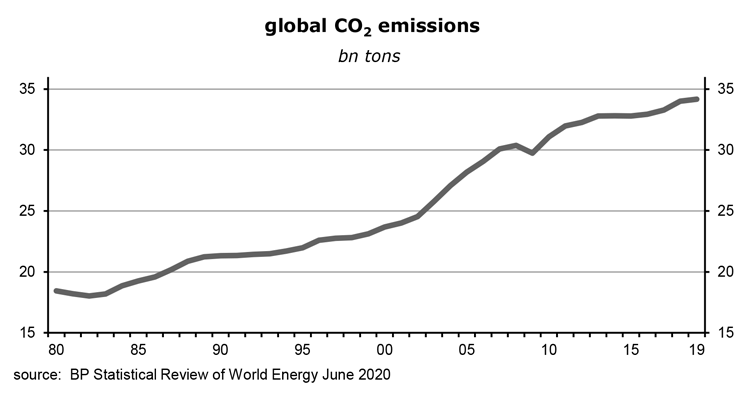

- In OECD countries, and contrary to general perceptions, the emission of CO2, the most important greenhouse gas, is on a steady downward trend – real GDP rises but CO2 declines. As the two previous graphs show, US GDP has increased by about 36% in the two decades from 2000 to 2020 while CO2emissions have declined by 20%. Similarly in Germany: real GDP up 19%, CO2 emissions down 27%. These numbers confirm the hypothesis that slower GDP growth is associated with a faster decline of emissions, but it is also clear that if CO2 emissions are not reduced at a significantly faster pace it will not be possible to reach net zero by 2050 (which is the EU’s long-term target).

- Outside the OECD air pollution is still increasing strongly. The countries in this group account for about 85% of the world’s population, and most of them are poor. As they rise from poverty, people adopt western lifestyles – they buy cars, air conditionings, move to larger apartments and houses, start travelling and eat more meat, and so on, activities that have negative effects on the environment.

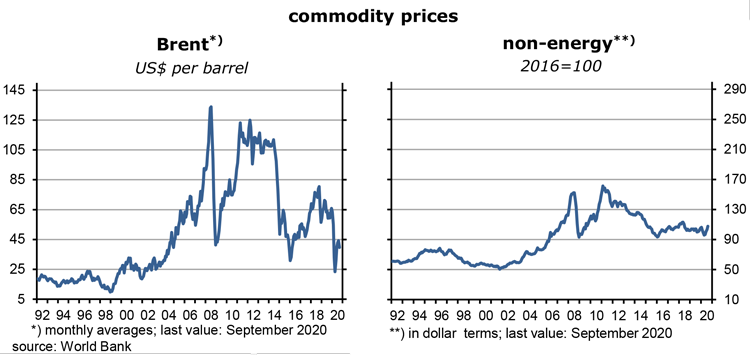

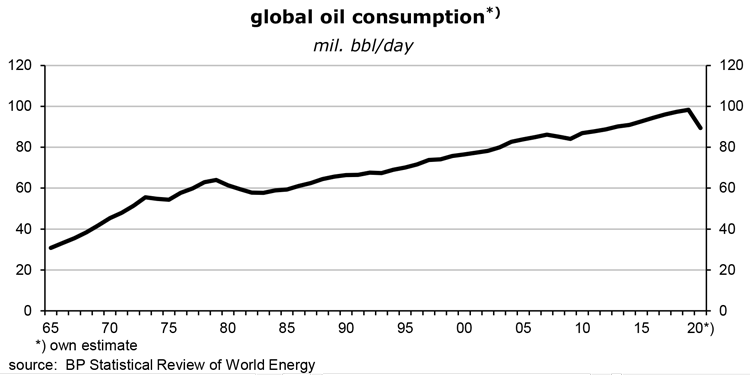

- Over the two decades to 2019, global oil production and consumption had on average increased by an annual rate of 1.3% . Corona has led to a significant decline this year, perhaps in the order of 9% y/y.Some analysts argue that the demand for oil will be down from here on and that we have finally seen “peak oil” (in 2019). I have my doubts. Global GDP growth will most likely resume once the pandemic has ended, perhaps at a reduced rate of 3½ % compared to 4% pre-Corona. It will once again mostly be driven by non-OECD countries which remain in catching-up mode, on the back of high investment ratios and large productivity gains. Going by past relationships, this suggests that oil consumption may increase by about 1% per year again – which in turn means that global CO2 emissions will continue to rise as well after the corona nightmare. Over the past two decades, their average annual increase had been in the order of 2%.

- The European Union, meanwhile, has become increasingly serious about the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. One third of the coming multi-year €750bn pandemic emergency stimulus package of the EU Commission is designated for green projects. And, at another front, the European parliament has just voted, with an overwhelming majority, to reduce CO2 emissions by no less than 60% between now and 2030. The commission had “only” proposed a reduction of 55%. In coming discussions among European institutions, a compromise will certainly be found and be put to a final vote in parliament on December 12, the fifth anniversary of the Paris climate treaty.

- For financial investors, the working hypothesis should be that they can rely on an acceleration of the green revolution – politics will create a lot of incentives and will earmark hundreds of billions of taxpayer euros for the mitigation of climate change. At this point, just about 5% of primary energy production comes from wind and solar. In electricity production, the ratio of renewables is already in the order of 40% (higher in some European countries), but in industry, agriculture, buildings and transportation it is much smaller.

- The transition to emission-free economies has only just begun, but momentum is building as most voters accept new climate regulations as well as higher prices of goods and services which contribute in one way or other to the deterioration of the environment. “Green” enterprises – many of which had fallen on hard times in the wake of Chinese competition – will grow strongly again from here on, with large variations between winners and losers. As always, not all new business models will succeed.

- Green bonds are booming. Increasingly institutional investors are forced by their stakeholders to buy them (and other “green” assets). So far, because their initial yield is usually somewhat lower than that of comparable regular bonds, they are a good deal for issuers. For investors who look for performance, they are marginally less attractive. The asset class is here to stay, though, as is the climate crisis.

stimulative fiscal policies are riskless, not reckless

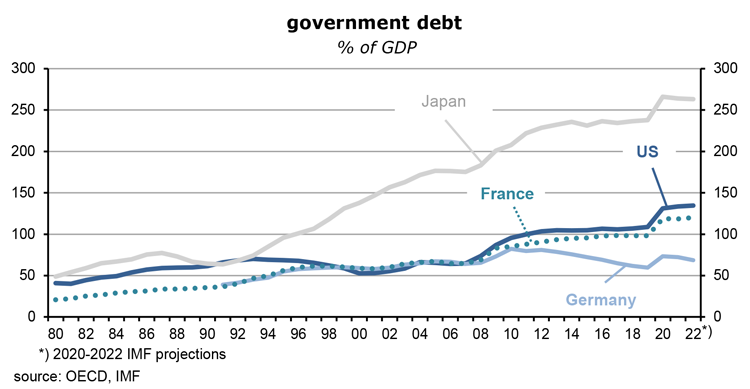

- Massive fiscal stimuli and budget deficits have pushed up government debt to record levels in OECD countries, both in absolute terms and relative to nominal GDP. But that’s how it is supposed to be in a deep recession when the private sector’s demand for goods and services has collapsed. Investors are not worried at all that the mountain of debt will lead to an acceleration of inflation and a subsequent sell-off of government bonds. The main point is that the public sector’s additional spending does by no means compensate for the shortfall in private sector demand. The output gap can only be filled partially this way, and disinflationary or even deflationary effects will prevail.

- Investors are aware of the situation in Japan where government debt has increased for decades and is now, according to the IMF, in the order of 266% of GDP, without any visible worrisome impact on inflation and bond yields. All OECD countries have begun to resemble Japan. Even a return to full employment may not prompt an acceleration of inflation if Japan does indeed turn out to be the model followed by other countries.

- A look at today’s inflation-protected government bonds shows that consumer price inflation expectations remain very low. Investors believe that over the next ten years average annual consumer prices will rise by 1.7% in the United States, by 0.7% in Germany and Italy (!), and by minus 0.03% in Japan – and thus well below central banks’ medium-term inflation targets. The main outlier is the UK where 10-year inflation expectations are 3.1%.

- There may no longer be a trade-off between unemployment and inflation. The famous Philipps curve, central banks’ main analytical tool, seems to be dead, not only in Japan but across all advanced economies. Full employment does not necessarily mean that inflation will pick up dangerously any longer. No one knows why this should be so. Open borders, transparent markets (think internet) and low transportation costs have intensified international competition. It is possible that low-wage workers in emerging and developing economies increasingly determine the rate of wage inflation in rich countries. We are probably heading toward a global labor market. If wages are the main driver of overall costs and general inflation, stable consumer prices may thus be a structural feature of OECD economies for quite some time. A bond sell-off appears unlikely in such an environment.

- How about the argument that our children will have to pay for today’s debt excesses, popular among jurists? This is absolute nonsense. First, deficits are large but not excessive – because there are lots of underemployed resources which need to be activated to avoid lasting damage to the capital stock. This is the case in all OECD countries. Second, by keeping potential GDP growth on a steeper trajectory means that children will inherit more than they would otherwise – repaying the debt one day causes less pain because, ceteris paribus, they are better off. Third, one person’s debt is another person’s asset which makes this an issue of income and wealth distribution – which can be managed by future tax policies. Fourth, if central banks succeed to achieve their 2% inflation target the real burden of the debt will steadily shrink – which argues for issuing government debt with long maturities; the real value of today’s government bond issued at 100 will have shrunk to 82% after ten years, and to 55% after 30 years. Fifth, a country’s debt can only become a problem if it is denominated in a foreign currency or if the government is unable to control the central bank that issues the currency (as in the euro area); this may become a problem for France and Greece some day but not for the euro area as a whole – because it is a net exporter to the rest of the world; this risk may become a driver of further fiscal integration of the region.

- The message for investors is that, at least in the near future, changes in government deficits and debt have little, or no negative influence on inflation and bond yields. For equities, expansionary fiscal policies are actually positive – as long as output gaps remain large.

ECB moves below the zero lower bound on interest rates

- Monetary policies are also very stimulative – or try to be. In the OECD area, inflation has been stubbornly below central bank targets of around 2% while inflation expectations suggest this undershooting will continue well into the future (as I have shown above). Expansionary policies are therefore a must. They are less urgent in the U.S. because actual inflation there is fairly close to the 2% target. But, since the Fed is tasked with bringing about full employment, it is also forced to stimulate the economy as much as it can; unemployment is still at 8.4% and therefore very high by American standards; moreover, the Fed also wants to prevent a new jobs-destroying appreciation of the dollar.

- Central banks are pushing on strings, though – they have lowered policy rates to zero, and in some cases below zero, and have also flooded the banking system with liquidity, but they cannot force consumers and business to borrow and spend more (and thus help to close disinflationary output gaps which are mostly in the order of 10% of GDP – with the exception of some East Asian countries). When demand is depressed as a result of high underemployment, stagnating or falling household incomes, and worries about health, attractive borrowing conditions are helpful but they do not change the all-important expectations about underlying economic risks.

- This is the hour when fiscal and monetary policies are de facto merging. Central banks are state agencies, a fact which becomes obvious in a crisis like the present one. They are not as independent from governments as they like to think, especially in the euro area. When inflation targets are met, or being undershot, central banks have to support the other economic targets of governments.

- Christine Lagarde and Isabel Schnabel of the ECB have recently argued that the central bank’s corporate bond buying program must not necessarily reflect the structure and pricing of those bond markets. Market prices are often distorted because externalities such as the pollution of air, soil and water, or climate change, or time wasted by commuting to work, or the cost of disposing of nuclear waste, are not fully taken account of. In other words, the ECB can to some extent pursue green policies and thus support the policy re-direction of euro area governments and EU institutions. This will boost the relative prices of green financial assets.

- Another new feature of monetary policies is the diminished relevance of the zero lower bound of interest rates. So far, the assumption has been that central banks can lower their policy rates only just a little into negative territory. If they fall too much, bank deposits would disappear as depositors will shift their money into cash. The interest rate on cash is obviously zero (in nominal terms) which is better than being charged for holding current or time deposits at a bank. This would destroy a major source of bank revenue and put the banking sector as such at risk, and with it an essential element of the economy’s infrastructure.

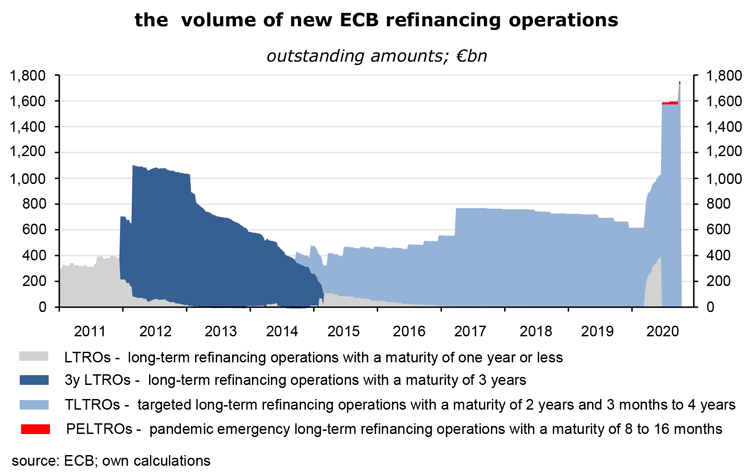

- In recent years, the ECB has developed an instrument called Targeted Longer-Term Refinancing Operations (TLTRO) which has effectively removed the zero lower bound, without putting at risk the health of the banking sector. Of the balance sheet total of about €6.5tr, 26% are already in the form of TLTROs.

- Under this facility, the ECB encourages banks to lend to the private sector. The more they lend beyond a certain threshold, the lower the interest rate on their borrowings from the ECB and thus their cost of funds. Since the rates are negative, banks are de facto rewarded to take ECB money. Theoretically, they could get funds at minus 3% and lend them on to their clients at minus 1%. In this example, they would earn an interest margin of two percentage points while depositors would not be affected. They would continue to earn a zero interest rate, as on most current accounts these days, or even a positive rate – business as usual!

- The ECB is not there yet, but a taboo has certainly been broken. Some time ago, the Bank of Japan has broken another one: it now intervenes in government bond markets with the aim to keep 10-year yields at the level of money market rates. In this way it subsidizes the state’s long-term borrowing and creates a flat yield curve. A steep yield curve stands for expansionary monetary policies, an inverse one for restrictive policies. There have been no adverse effects on inflation expectations. Investors don’t mind.

- They also don’t mind that the BoJ monetizes a major part of government debt: the Treasury issues bonds which are directly and indirectly purchased by the BoJ. The net position of the government does not change in the process: the Treasury increases its debt while the assets of the BoJ increase by the same amount – and they have the same composition! These are the wonders of an economy that operates far below potential.

- This is certainly the time to think about novel policy instruments. Many supply chains have been, and will continue to be severed while the structure of demand and supply is changing in a fundamental way. This results in the persistent underutilization of resources, ie, high unemployment and low rates of capacity utilization which in turn causes persistent and pervasive uncertainty which boosts savings and depresses investments – and leaves all of us poorer in the longer term.

- Willem Buiter, the former chief economist at Citigroup and now a visiting professor at Columbia, argued last April that the most effective medicine to prevent such an outcome would be monetary-financed “helicopter money” by national central banks to governments, in the form of cash transfers of 20-30% of GDP. Such handouts from one government agency to another would have the scale to outrun the meltdown, leave no debt overhang and would not require future counterproductive austerity. He admits that probably things have to get worse for longer before such a policy will actually be considered. In a recent interview he emphasized that the medicine should only be taken by central banks and governments which have a record of prudent fiscal policies.

- And the bottom line after all these fine arguments? What should investors do? The economic risks are mostly still to the downside in Europe and America as the second wave of virus infections looks almost unstoppable. Expect more uncertainty, more lockdowns, further cuts in capital spending, new layoffs and bankruptcies and again a slowdown of GDP growth. Cheap assets have underperformed during the recovery from last spring’s stock market crash – their time has now come again, I would guess.

Read the full article in PDF format:

Wermuths Investment Outlook October 15, 2020