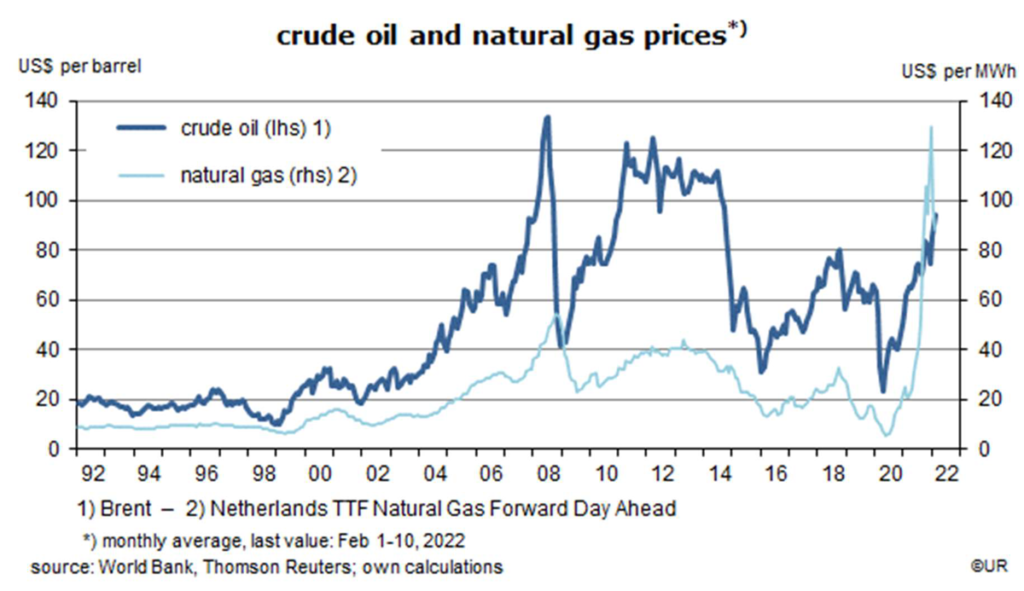

Market Commentary: Oil and Gas prices likely to crash

What goes up must come down. Fossil fuel prices have increased so much they have lost touch with fundamentals and are therefore bound to fall a lot (see graph #1). The only questions are: when and how much?

The main reason for the coming crash is that general inflation has recently risen way beyond the growth of household incomes. In the US, for instance, consumer prices were, shockingly, plus 7.5% y/y in January – while average weekly earnings were up just about 5% y/y. The same has recently happened in most other rich countries.

This big decline of purchasing power will in turn trigger a global recession or at least a significant slowdown of growth, starting in economies which are net importers of fossil fuels, such as the EU, China, the US, and Japan. In addition, the main central banks are now starting to scale down quantitative easing and start raising interest rates even though this will pro[1]cyclically strengthen the recessionary forces of the fossil fuel price explosion.

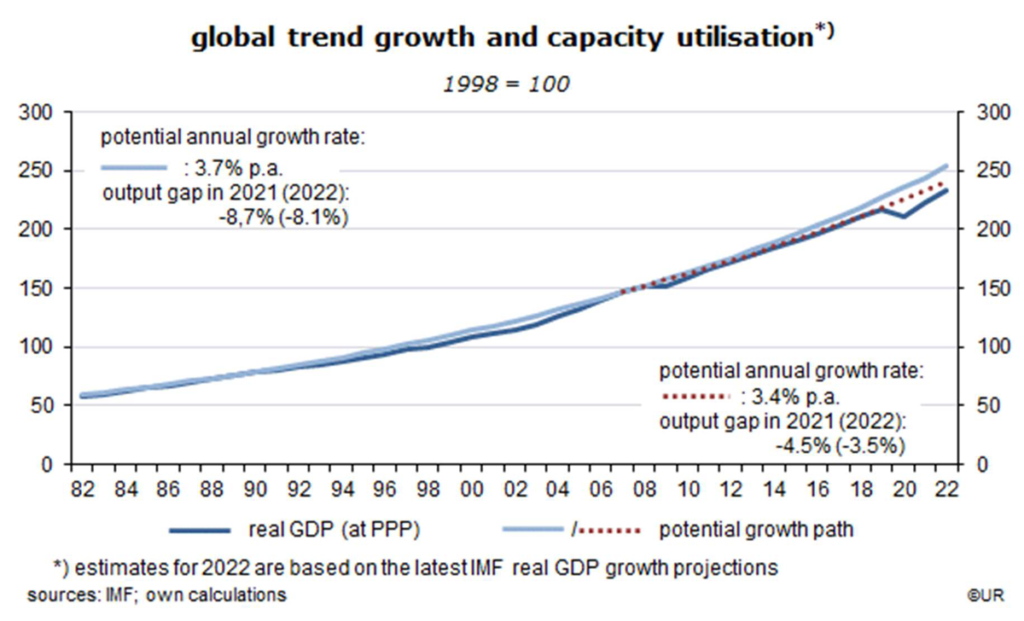

These two developments alone suffice to cause a crash of oil and gas prices. And there are no elevated inflation expectations to speak of: output gaps are still quite large (graph #2) and it is therefore not easy for wages to catch up with inflation. Inflation expectations – which are necessary to set in motion a sustained wage/price spiral and sustain the fuel price explosion – remain quite subdued. Inflation-linked government bonds suggest that the expected, i.e., implied average annual consumer price inflation rates for the next five to ten years range between 0.6% in Japan, to 1.8% in Germany and 2.5% in the US. Bond yields way below actual inflation show that investors remain relaxed about inflation risks. There is also no flight into gold, the ultimate inflation hedge (nor into yen-denominated assets). Markets tell us that today’s record high inflation rates are probably transitory, which is a corollary of saying that oil and gas prices are considered to be much too high.

Near term, markets will remain dominated by Corona and the fear of a war in the east. Once these risks fade, the main scare factors which have driven commodity prices and general inflation will disappear. There is no scarcity of oil and gas on a global level, especially at today’s elevated price levels. There are early signs that the tide has started to turn, but setbacks can obviously occur anytime.

I would expect that the oil price will be back to perhaps $50 a barrel over the course of the year (or less, in a sell-out) while gas prices might fall by about 70% to reach a “normal” level. It is increasingly dangerous to stay long energy.

All this means that consumer price inflation rates here in Europe are about to peak in the coming months. Bond markets will remain weak near-term – but will not crash. Equities are considerably more exposed.

Read the full article in PDF format here.