Market Commentary: Germany’s fairy tale of the missing worker

Dieter Wermuth, Economist and Partner at Wermuth Asset Management

According to calculations and surveys by the government’s Nuremberg Institute of Labor Market Research there were 1.82 million vacancies in Q3 2022. The debate about missing “qualified” workers has once again heated up in recent weeks; it is a favorite topic in talk shows, triggered by new reports from the Boston Consulting Group and the DIHK, the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce. The DIHK argues that “in combination with high energy prices and the challenges of the transition toward climate neutrality, increasing staffing problems may lead to a relocation of production and services to foreign countries … this is not only a challenge for firms but may also jeopardize important projects such as the energy transition, digitalization and the improvement of the infrastructure – for these tasks we need people with practical skills.” Never before had there been such a severe shortage of qualified workers.

These are, of course, the usual complaints of business. Since about 1 million of the almost 2 million vacancies could realistically be filled while the average annual value added per worker is presently €84,400, the country’s GDP is therefore €84bn less than it could be. It is the result of dividing the latest GDP number of €3.858tr by total employment of 45.7m, times 1m. We are thus talking about a “lost” output of 2.2% of GDP, year after year.

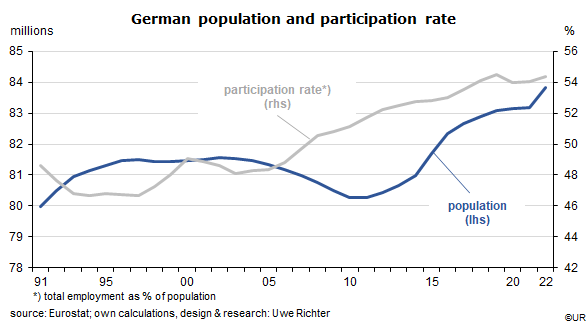

No doubt: if all job openings could be filled by competent workers, it would be good for us, now and in the future, at least somewhat. To put things into perspective, though, the German labor market is more robust and dynamic than it appears in today’s public perception. For years now, the number of new jobs has been increasing at an annual rate of about 1% or almost half a million, including during the recent economic weakness. The population has grown from 80.3m in 2011 to almost 84m in 2022 (0.4% p.a.) while the participation rate has reached 54.5%, one of the world’s highest, after just 52% eleven years ago. As to the unemployment rate, it is 3.0% if the ILO methodology is used (5.5% in German terms). Among the large economies, only Japan has a lower rate.

Even so, a larger supply of qualifies workers would help, for instance to strengthen the German pay-as-you-go pension system and lower the financial burden of younger generations. Many ideas are being discussed how to bring this about, such as a better and more comprehensive provision of public child care, improving the so-called dual education system to make sure that all youths learn some useful skills, promote female labor market participation, a more flexible organization of the retirement system (more flexibility, raising the standard retirement age to 70 years) and create more incentives for immigration into the country’s labor market.

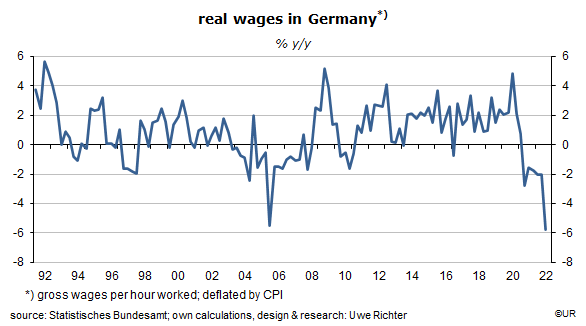

In all this, wages are not a topic. If there is a shortage of goods, capital or labor in a market economy, the price mechanism typically solves such problems quickly and in an almost unnoticed way. Prices and wages rise and thus increase the supply. Why should it be different on Germany’s labor market? Higher wages and salaries are the obvious and appropriate solution of the qualified labor shortage. At the same time, no one should be surprised that this changes the macro structure of the income distribution: nurses, old age care workers, plumbers, butchers and young people in professional training would be relatively better off while brokers, doctors, notaries, or asset managers would be at the losing end. This will only work if the groups which are currently underpaid get organized, not a small task. But it would be extremely surprising if this would not get us a large step closer to a situation of full employment in areas with a lack of skilled workers. Markets usually work.

Since the turn of the millennium, average German real wages – nominal hourly wages minus inflation – have increased by just 0.5% per year. In other words: by almost nothing at all. This has been a very long time. For household consumption and the growth outlook in general much would be gained if the income of workers in sectors characterized by labor shortages would be raised more than proportionally, and for several years. This is an aspect that must be part of the discussion about the lack of workers – there will be no such lack anymore as soon as wages are a lot more attractive than today.

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he was also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.