Market Commentary: Why yield curves are inverse

Dieter Wermuth, Economist and Partner at Wermuth Asset Management

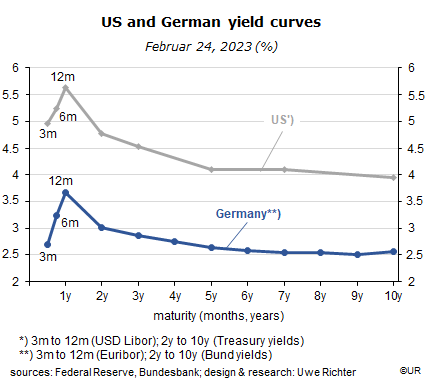

After the FED and the ECB had begun to raise policy rates in big steps last spring and summer, in response to unusually high inflation rates, yield curves have inverted. In the meantime, American and European money market rates are significantly higher than yields of long-maturity government bonds, by more than 100 basis points. Instances of inverted yield curves are not unusual in economic history, but on average, short term rates have been lower than long-term yields because financial investor demand, and get, a compensation for transferring their savings to borrowers for a long period of time: the longer, the higher the risk, and the larger the price volatility of fixed-income securities.

The reason why policy rates as well as Libor, Euribor and the other money market rates driven by them are so high right now in both relative and absolute terms is obvious: central banks try to dampen overall demand and thereby inflation. Whereas high price levels have not only been the result of expansionary monetary policies but also of the energy price shock, monetary policy makers regard rising interest rates as the only effective instrument in the fight against inflation, even if this contributes to a recession. As it is, inflation rates at the earlier stages of the value-added process are already on the way down, including imports, wholesale trade and producer prices, just as assets prices of real estate and shares in listed companies. But, as always, it takes time for these developments to show up in consumer price inflation which is at the end of the chain.

In the US, the core inflation rate of consumer spending, for the Fed an important leading indicator for headline inflation, is still at 4.7% y/y, slightly up on the outcome for December. Market participants increasingly expect the effective Fed Funds Rate, today at 4.6%, to rise to perhaps 5.5%. Similarly in the euro area, where the core inflation rate, at 5.3%, is still way above the 2% target for the Harmonized Consumer Price Inflation rate. The ECB, plagued by a guilty conscience after long years of expansionary policies and trying to re-establish its reputation as an inflation fighter, is obviously planning to raise the bank deposit facility rate, presently its main policy rate, from 2.5% today, by 100 and possibly even 150 basis points.

For me, this is clearly over the top. Inflation is already on the way down, the result of the significant loss of purchasing power in the wake of the energy price explosion, the stagnation of real GDP that started last quarter, and increasingly restrictive monetary policies. So far, neither in the US nor in Europe have there been signs that a new wage-price-spiral has begun. Central banks can afford to wait. Nervousness or the feeling of guilt are always bad advisers.

Why are long-term interest rates so low, in spite of a new large increase of government debt (military, energy subsidies) and the plans to shrink central bank balance sheets by reducing bond portfolios. This is especially relevant for European bond markets. Financial investors seem to bet that the era of high inflation has been transitory and is about to end.

Sometime soon, probably starting next fall, restrictive monetary policies will be reversed, both in the US and in Europe. From that point onwards, yield curves will begin to “normalize”, ie, return to their usual positive slope. How much of this will be caused by lower policy rates on the one hand and higher or stagnant bond yields on the other is hard to predict. But I am sure that neither the Fed nor the ECB are contemplating a return to their previous zero interest rate policies. More precisely, it is quite unlikely that the Fed Funds Rate or the ECB’s deposit rate will fall back below 2%. But fall they will.

Once the next economic expansion gains track it is a foregone conclusion that inflation expectations will rise again, even before actual inflation rates have turned up from their lows. This means rising long-term interest rates.

In other words, for the foreseeable future financial investors will be better off at the short than at the long end of the yield curve.

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he was also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.