Market Commentary: European monetary policy – dangerously restrictive

Dieter Wermuth, Economist and Partner at Wermuth Asset Management

Since last summer the ECB has raised policy rates by four percentage points and it is possible that there will be two more 25 basis point hikes between now and September. Also since last summer the central bank has reduced its balance sheet by an estimated 18% (end of June 2023) and has thus withdrawn a significant amount of liquidity from the economy. To borrow money has not only become much more expensive, it is also difficult to get a loan at all – banks are rather choosey these days.

The idea is to bring down consumer price inflation sustainably from its present 6.1% y/y to the 2% target, in order to avoid the impression that the ECB might not mean business. It would otherwise lose credibility – and thus its main asset.

The ECB has been very restrictive since last summer. But Board members keep saying that it is better to tighten too much than too little. As it is, the economy of the euro area has stagnated for three quarters already while leading indicators suggest that inflation has peaked and is coming down quickly – and that no further restrictive measures are needed.

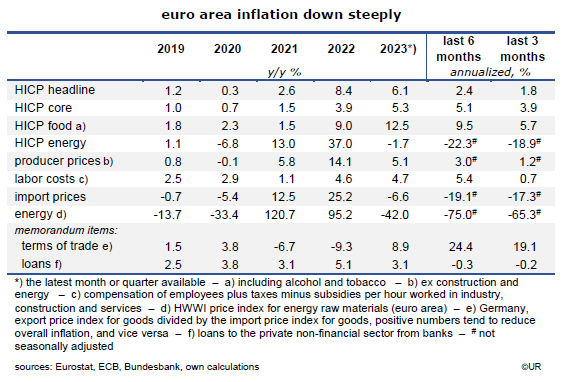

The most important numbers are, for the harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP), the 6- and 3-month annualized rates of change. They have fallen to plus 2.4% and 1.8%, respectively. Further up on the value chain, the rates for producer prices (ex construction and energy) were just 3.0 and 1.2%. On present trends, consumer price inflation will reach its 2% target within half a year.

Will this be a temporary or a more durable success? It will be the latter, going by the strong increase of the (German) terms of trade and, on the cost side of the picture, the decline of import prices: they were down 6 ½% y/y this spring and have fallen at annualized 6-and 3-month rates of almost 20% (!). The recent appreciation of the euro and the large decline of commodity prices have left their mark. Mostly good inflation news from the labor market as well: labor costs, the most important cost component, have increased at an annualized rate of only 0.7% over the past three months, despite the need of workers to catch up after the large reduction of real incomes, caused by record-high inflation, and their strong position in wage negotiations. There is no sign whatsoever of a new wage-price-spiral.

Overall, recent slow or even non-existent real GDP growth has widened the output gap of the euro area economy. It is difficult to raise prices and wages in such a situation.

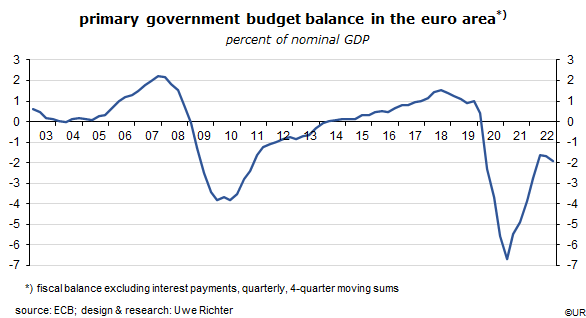

Inflation is also kept down by the large swing in the aggregated primary balance of government budgets: between the first quarter of 2021 and the fourth quarter 2022, the balance decreased from minus 770bn to minus 260bn euros, or by 4.8 percent of nominal GDP. In other words, fiscal policy has moved from very expansionary (COVID 19) to more or less normal and has thus exacerbated the deflationary effects of monetary policies – a double whammy, so to speak (Doppel-Wumms).

Incidentally, this resembles US developments: the primary deficit there declined from 13 and 11 percent of GDP in 2020 and 2021 to just about 3 ½ percent last and (probably) this year (see Economic Report of the President 2023, p. 80). As on this side of the Atlantic, restrictive monetary and fiscal policies have also led to a double whammy – which largely explains why the US economy has lost its momentum.

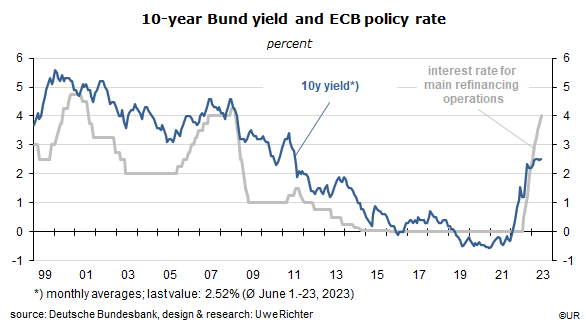

One could argue that the ECB’s policy rate of presently 4% is not really restrictive, given consumer price inflation of 6.1% y/y. But it is not the level of the two variables that matter but their dynamics, the way they have changed since the summer of 2022. The 400 basis point increase of the main refinancing rate as well as banks’ deposit rate have pushed the yield of 10y German government bond yields from -0.5% to +2.5%. Since this increase was about 100 basis points less than that of (short-term) policy rates, this has resulted in an inverted yield curve, again similar to what we see in the US. For banks – which typically borrow short and invest long (loans, bonds) – this has resulted in a margin squeeze which forces them to shrink their bread-and-butter business. This has another negative effect on overall demand.

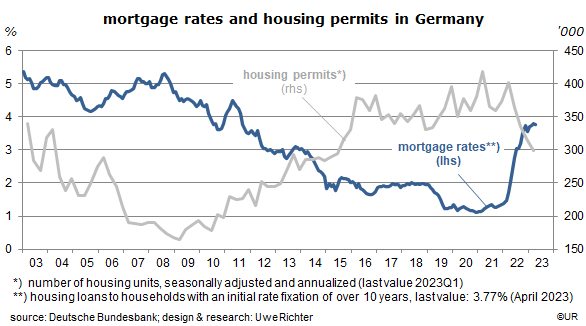

The main impact of the large increase of long-term interest rates has been on capital spending and thus on the growth rate of potential GDP. Residential housing in particular has taken a big hit. In Germany, the average monthly debt service is presently about three times larger than before the Corona crisis – which had begun in February 2020. For many households buying a home has become prohibitively expensive. The message of the numbers is clear: since early 2022 building permits have crashed from 400,000 annually to just 300,000, a reduction by a quarter. At the time of their inauguration in December 2021, the coalition government of Social Democrats, Greens and Liberals had announced that they would aim for the creation of 400,000 housing units annually. They had obviously not taken into account that mortgage rates would rise so much. Since population growth has accelerated briskly once again (Ukraine) there is now a glaring lack of affordable housing. Even so, German real estate prices have fallen, not increased, so far this year, and at larger rates than in decades. It is clearly an affordability issue. The situation is probably not much different in the other 19 member states of the euro area.

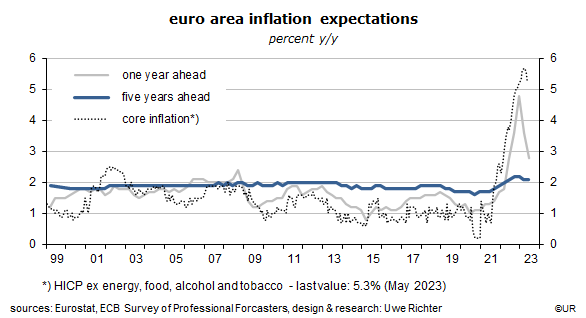

If I look at the ECB graph of the inflation expectations of professional forecasters, I might conclude that there is actually no need for those high policy rates, and in particular no need for even higher ones. The ECB can be proud about the fact that expectations have been very close to 2 percent right from the start in January 1999, exactly on target and well-anchored by now. A success story. There is obviously room for less restrictive policies.

But things are more complicated than at first sight. Who can guarantee that inflation expectations will indeed remain at 2% when month after month actual inflation rates are at 6% or more? If businesses and workers come to the conclusion that, say, 5% is the new normal, they will try to adjust their prices and wages accordingly – and this would spell the end of those supposedly well-anchored 2% inflation expectations and the reputation of the ECB as a determined inflation fighter. These new expectations would become the most important determinant of future inflation rates, a self-fulfilling prophesy (Inflation expectations and their role in Eurosystem forecasting. ECB Occasional Paper No 264, September 2021).

This is the main reason why the ECB keeps its foot on the brake. From its perspective everything necessary must be done to avoid the impression that it is not really determined to bring headline inflation sustainably down to 2% – and then keep it there. It implicitly accepts that such a policy may cause a stagnation of the economy, if not a recession. It’s where we are today. But there are limits. The ECB cannot fight inflation no matter what. Most importantly, unemployment has to be closely monitored. If an increase of unemployment were to be attributed to restrictive monetary policies, the commentariat would begin to propose an end of ECB independence and to make it part of fiscal policies (of the euro group), perhaps along the lines of the Turkish model.

Price stability is an important goal of economic policies, but not the only one. By a happy coincidence, euro area employment is still increasing at a rate of somewhat more than 1% y/y and no one has begun to attack the ECB for its failure to boost GDP growth. Its reputation has not suffered so far.

At the meeting on July 27, policy rates will almost certainly be raised by 25 basis points. Some members of the Board argue that another step of this magnitude may be warranted on September 24 if, by that time, core inflation has not fallen considerably. At the meeting, they will know what happened to euro area inflation in June, July and August. Trusting the leading indicators I look at I am convinced that inflation will decline further, and that another rate hike will not be necessary. Monetary policy is close to its turning point.

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he was also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.