Market Commentary: Germany’s debt brake must be changed – or abolished

The Federal Republic has rock-solid public finances, especially in comparison to other large industrialized countries. Quite surprising then that the media are dominated by a heated debate about the question of how to reduce the government’s budget deficit, as if the future of the country was at stake. The deficit will be a mere 2.2% of GDP this year.

Basically, a government can borrow as much money as it likes, it all depends on how the money is spent, on consumption or investment. Savers will only earn interest income and dividends if there is an opposite side which borrows money, successfully invests it and is able to service its debt. Servicing the debt is nothing else than a transfer of funds to savers. In a market economy there will be neither enough private nor public investment, nor a capital market or economic growth and a rising standard of living. Germany’s so-called debt brake, if applied rigorously in its present form, will bring about a debt-free government in the long run. As a result, the market for safe financial assets – government liabilities – would disappear.

If the government does not borrow in dollars or another foreign currency it cannot become insolvent. It is for this reason that it is considered to be the ultimate safe borrower. The central bank, as part of the state, can always generate all the domestic-currency liquidity the government needs to service its debt – by monetizing, or buying its bonds and other forms of debt. It’s called printing of money, and there are no limitations on this process, except if inflation gets out of hand. For the countries of the euro area this rule does not fully apply: none of them “owns” the ECB. But it can be assumed that the central bank will come to the rescue if a member country is at risk of defaulting. This aid will only be given with strings attached. The bailout of Greece in 2010 to 2015 has shown what this means in real life. After years of austerity policies the country is now approaching the median debt-to-GDP ratio of the other euro member states while the Maastricht deficit rule has already been achieved, all this largely without support from a debt brake. International rating agencies are impressed and have begun to upgrade the country’s credit worthiness.

I am not making the case for ever larger government debt but rather for excluding government investment spending from the calculation of the permissible deficit under the debt brake. One statement can be made with a large degree of confidence: government spending on investments has a relatively high rate of return, especially in Germany where the capital stock must urgently be modernized. According to Michael Hüther, the director of Cologne’s Institut der deutschen Wirtschaft, “a debt-financed spending on infrastructure, based on the so-called Golden Rule, should be possible.” In an article, published 2019 in the economic policy magazine Wirtschaftsdienst, he comes to the conclusion that “the proposition of strong productivity effects of public sector investment spending can be confirmed. This applies, most of all, to infrastructure, but also to education.” (page 319) He refers to analyses in the 2002 and 2008 annual reports of the government’s Council of Economic Advisers. For me, this means that the government can and should pursue debt-financed capital spending even beyond the limits of the debt brake. From today’s perspective, this is self-financing, meaning that future tax receipts will be more than sufficient to cover expenses resulting from the additional debt, and should not be limited by the restrictions of the debt brake.

Infrastructure is not just streets, railways, optical fiber grids or schools. Such a definition is too narrow. In today’s world, a large part of economic growth requires software, the analysis of data, the digitalization of processes, services of all kinds and, increasingly, the use of artificial intelligence, and these, in turn need spending on education and research, ie, on human capital. Wages paid to kindergarten and school teachers add more to the productive capital stock of a country than another football stadium or gambling casino. In a wider sense even some parts of the social budget could be considered as spending on the human capital stock – because social peace is needed for this kind of investment. I know that the time has not yet come for such an approach.

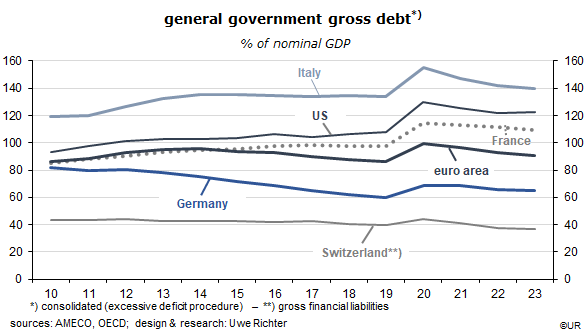

The following numbers from the OECD’s new Economic Outlook show that economic growth is uncorrelated with government debt: in Germany, gross government liabilities, ie, government debt, will be just 65.4% of nominal GDP in 2023. For the six other large democratic industrialized countries of the G7-Group, the debt-to-GDP ratios are the following: US 120.9%, Japan 244.8%, France 118.2%, UK 101,1%, Italy 148.2% and Canada 100.6%. Germany has a low level of debt but grows only disappointedly slowly while the US doesn’t care much about government debt but manages to grow briskly. France and Canada have both achieved fairly rapid growth while Japan and Italy are highly indebted and grow only slowly. In other words, there is no clear correlation between government debt and the primary objective of fiscal policies – to improve general welfare.

Low government debts have some important advantages: they bring about low real and nominal long-term interest rates and a low share of spending on debt service in total government spending. This creates room for maneuver in economically difficult times, ie, room for additional spending; it may also strengthen the exchange rate and reduce inflation.

On balance, an economic policy tool like the debt brake in its present form is a self-inflicted growth brake which reduces the international competitiveness of Germany and the 19 other countries of the euro area. It must urgently be reformed – or abolished.

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he was also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.