Last January the EMU, the European Monetary Union, had turned twenty-five. Overall, the euro has been a successful project which has not only shown its resilience in several crises but has also provided price stability. The average consumer price inflation rate (2.1%) has been lower than in Germany over the previous quarter century (3.0%) despite the fact that several high-inflation members (of the Club Med) had joined the currency union. Even so, it is still an unfinished project because there is neither a banking union nor a capital market union. As long as this is the case the euro has no chance to catch up with or surpass the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Going by stability criteria such as the balances on current account, inflation rates or government budget deficits, the euro should be the more attractive currency for financial investors.

That these fundamentals don’t seem to matter much is because the US remains the most important world power on the one hand, it’s the safest place, and is home of the largest and most liquid capital markets. A few days ago, the Financial Times has published an article which has provided some statistics which substantiate this statement: there are only three US stock exchanges where firms can list their shares, compared to 35 in Europe; shares can be traded on no less than 41 European vs. 16 US exchanges, and America has only one central clearing house – Europe has 18! In other words, Europe’s stock markets are hopelessly fragmented, where each one is small, without any evidence that this will change in the foreseeable future. In its latest annual report, the German Council of Economic Advisers had listed, in a detailed chapter, the various obstacles that stand in the way of an efficient, streamlined and common European stock market (SVR, 2023/24, paragraphs 238 to 276). Since too many cooks spoil a meal, as they say in Germany, the solution is probably that a small group of countries must go ahead with reform, including France, Germany, Italy, and the Netherlands, forcing the others to join – or face irrelevance.

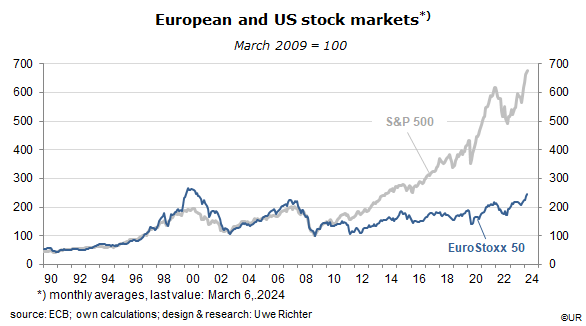

The authors of the FT article argue that the fragmentation of European stock markets is an important reason for their relatively poor performances since 2009.

Over the past 15 years, the S&P 500, America’s benchmark stock index has gained no less than 580%, compared to the EuroStoxx 50’s 140%. In the decades before, the two indices had moved more or less in lockstep. Whether this huge divergence has indeed been caused by differences in the respective structures of stock markets cannot be determined empirically, but must have played a significant role. The main reason has been the growth of the tech giants’ market value. Nothing comparable had taken place in Europe. The market cap of AI firm Nvidia, a company almost no one has heard of in Europe, is about just as large as that of the German DAX – which include the county’s 40 largest companies. For decades, the price-earnings ratio of American companies exceeded that of European firms by a large and almost structural margin – which has recently prompted Linde, BioNTech, CureVac, Spotify and Birkenstock to do their IPOs (initial public offerings) in New York rather than in their home markets – these are less liquid and thus less attractive in terms of pricing (a similar argument was made in a recent study by DB Research). Financial investors pay higher premia than in Europe, and European firms pays less for their equity.

From an economic point of view, it is an advantage if the cost of raising capital is low (if the pe ratio is high). This stimulates capital spending and thus the growth of potential GDP and general welfare. European policy makers must urgently forge ahead with reforming the structure of their stock markets. Since the environment is extremely complex, they fear the resistance of interested parties which may lose their privileges. The reforms will not be a vote winner. So hand them over to the experts!

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he is also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.