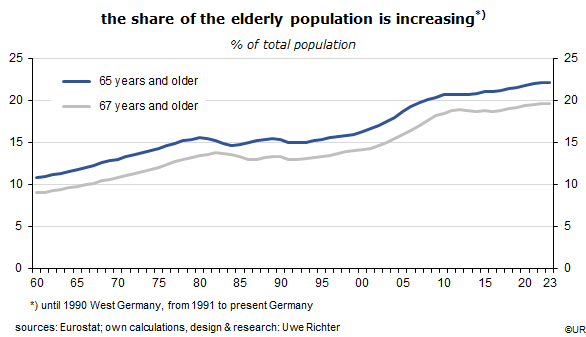

Since 1960, the share of people aged 67 and more has gone from about 9% of the German population to 20% now. As life expectancy continues to increase the young have to support more and more old people – their payments into the pension system, directly or indirectly via the government budget, are bound to rise further. So-called pension specialists keep publishing apocalyptic doomsday scenarios about the unsustainable financial future of the present pay-as-you-go system. In reality, it is a rather small problem, compared to the slowdown of potential GDP growth and general welfare, or the threat from Russia, or the climate crisis. Politicians know what needs to be done, and there is plenty of time left.

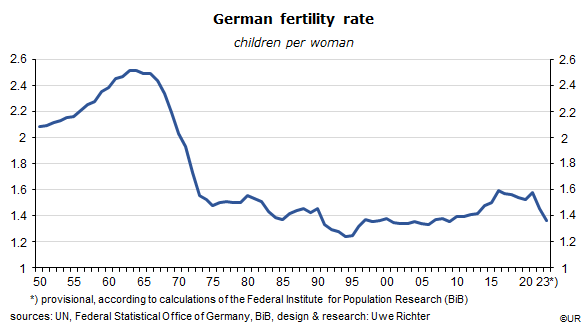

As in other European countries and in rich countries generally, the German birth rate has declined quickly and steeply since the baby boom of the sixties, from 2 ½ children per woman to about 1.4 – where it has more or less stabilized. Without immigration the population would have shrunk considerably by now. Moreover, the share of old folks would grow explosively over the next ten years, as the large baby boom cohort starts to retire. After that, things could be expected to stabilize.

The low fertility rate is actually a good thing. Most of all it is the result of the strong increase of the female participation rate (from 46.5% in 1970 to 75.9% today), the steady increase of financial assets and people’s trust in the social safety net – own children have become less important as the main financial support in old age.

In addition, climate change is human-made. Half a century ago, the Club of Rome had pointed out that slower – or negative – population growth is an important parameter in the fight against greenhouse gas emissions and the heating-up of our blue planet. The reduction of the birth rate has been caused by women’s deliberate decisions and is regarded as a structural constant. The state should not interfere, even though, in Germany, it continues to hesitate to get rid of the so-called Ehegattensplitting in the tax code – which is an incentive for women to stay home and have children rather than to go out and have a career on their own.

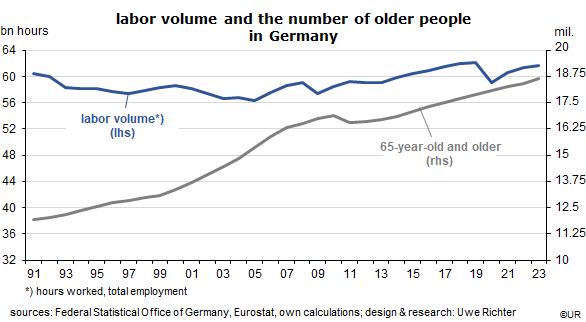

What can be done to reduce the financial burden of the young who have to support more and more non-active old people? To put it simply: the amount of labor, in terms of total hours worked per year, should not decline relative to the number of old people who do not work for money. De facto, this rule has been missed by a large margin over the past three decades: while the number of hours worked has increased by somewhat more than 5% (to 61.7 billion annually), the number of non-active old people has grown by more than 50% (to 18.7 million). This cannot continue.

The effective number of hours worked can be increased by several means:

1. The female participation rate can be raised further – by extending and improving pre-school child care as well as primary schools, along Scandinavian lines. Such spending should be regarded as investment because it not only boosts the growth rate of potential GDP but most likely also of productivity: in general, women are better educated than men. This requires to give up the notion that women’s main role is that of a housekeeper. While much has been achieved already there is still a lot of room for improvement.

2. In addition the average length of the working life should be extended, possibly at a faster rate than the increase of life expectancy. If people want to work beyond the future legal retirement age of 67 they should be able to do so – the additional income should be taxed lightly, or not at all. This requires an attractive set of incentives. Not only would this raise the volume of total hours worked but most likely also the average professional qualification of the labor force. Part of such a strategy could be an occupational retraining of old workers who are physically exhausted. Many people enjoy their work – it’s better than walking the dog or go on a holiday cruise.

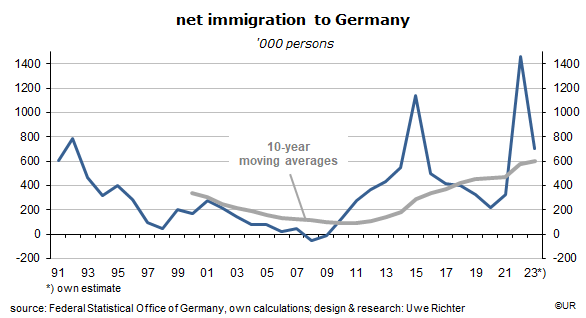

3. Germany is in the enviable position that many foreigners would like to come and make a living here – they are mostly young, often have children, are usually energetic and want to succeed in their job. That’s what the country needs. The optimal annual net immigration in terms of what is needed for the stabilization of the pension system lies between 300,000 (according to estimates of the Federal Office of Statistics of December 2022) and 400,000 (Council of Economic Advisers, the “five sages” of November 2022). These numbers cover immigrants from the EU – who are free to immigrate –, as well as asylum seekers who can show that they are persecuted in their home countries. These two groups come first, without quantitative limits. If they together account for less than the annual target immigration the rest can be allocated to other groups of immigrants. One idea is to establish departments in German embassies which pre-screen would-be immigrants. The staff could be on the payroll of the Federal Labor Office. They should aim to promote the recruitment of suitable candidates and facilitate their transition into German society, including language training in their home countries. This would reduce the illegal and often dangerous immigration across the Mediterranean. Incidentally, over the past decade the average annual net immigration has been no less than 600,000. At this point, there is no risk that the German pension system is about to collapse.

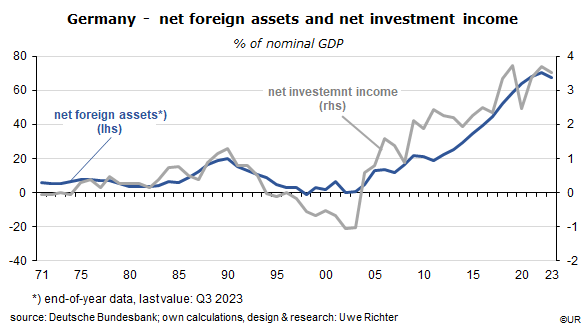

4. At least partially, the income of the old could be supported by revenues from the country’s large foreign capital stock, just as other countries with large surpluses in their balances on current account. These surpluses are nothing else than net capital exports. Think of Norway or the Gulf states – once their income from selling gas and oil declines or ends, they expect to fill the gap by relying on the interest income and dividends generated by their foreign assets. Since 2004, Germany’s net foreign assets have strongly grown, thanks to large current account surpluses, and have reached 68% of nominal GDP by now; annual net income from that source has been no less than 3.5% of GDP. I guess that foreign assets will increase further in the near term, accompanied by rising revenues.

To avoid that only a small number of wealthy people benefit from these revenues, the public pension system could issue large long-term and euro-denominated bonds and use the money to fill a fund with foreign equities and bonds, not for near-term gain but for the long term. Role models could be US university endowments which typically invest 60% in equities and 40% in bonds. Part of the income from these sources could be used for current expenses (of the pension system), the other part would be reinvested. Since the bonds of the Social Security System would come with a guarantee of the government, they would have an AAA rating as well. This means they can presently borrow at 2.4% for ten years. The assets, on the other hand, can be expected to yield 6 to 7% in the medium term – if they are well diversified. The difference in yield is mostly due to the fact that foreign assets carry a relatively high yield premium, equities in particular, and are less liquid than the Social Security bonds. In other words, the stabilization of the pension system would not only rely on the immigration of foreigners but also on foreign capital income. After some generations it should be possible to lower pension contributions. It might be worth a try.

The bottom line is that there is a range of adjustable screws which can be turned. Young people do not need to be afraid about their income in old age. But it certainly needs a broad consensus in society to implement the needed reforms – and a long-term approach.

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he is also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.