Market Commentary: The European Union: economically a giant, politically still a dwarf

Geopolitically, the EU is almost irrelevant. There is the risk that its influence will shrink further if Donald Trump becomes US president again in January 2025, even in matters which are of direct concern for Europe, such as in Ukraine or in the neighboring Near East. Trump and Putin could strike deals without consulting the Europeans or asking for their permission. A horror scenario.

In the October 21st edition of the Economist I found the following two sentences: “… (the EU) is a construct perfectly adept at standardising phone chargers and making farmers rich, but one that scarcely matters when it comes to high politics. A fortnight of discussions has made the EU look as plodding as ever: a club that does not shape geopolitics so much as to endure its effects.” I guess that this is not only the prevailing view in the anglophone part of the world but also in other regions.

So far Europeans have lived comfortably without geopolitical ambitions, driven by the reconciliation between France and Germany, determined to avoid another war on the continent, all under the implicit military protection of the United States. Europe has indeed lived more or less peacefully since 1945, and even the revolutions around the year 1990 which ended the Soviet de facto occupation of central and eastern Europe have not been bloody affairs. The standard of living is higher than ever, societies adhere to the rule of law and the differences between rich and poor are smaller than in most other countries.

At this point, the EU consists of 27 member states, of which 20 use the euro, the common currency, while 23 belong to the Schengen area which has eliminated all internal border controls. In Brussels, the assumption is that another eight (or more) countries will join by 2030. All have to accept the rules and regulations laid down in the so-called acquis communautaire and must (presumably) be members of the European Council. Candidates are Türkiye, North Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Albania, Moldovia, Ukraine, Bosnia and Herzegovina, plus, perhaps, Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. The EU’s population would increase from about 450 million today to more than 600 million.

It will obviously become more difficult to come to agreements and to speak with one voice. Fundamental reforms are badly needed. Governments in Berlin and Paris have recently rediscovered their traditional role of promoting European integration and have laid aside their quarrels about the question of whether nuclear power is green, or not, or how to proceed in military matters. They accept that there are more important issues right now – which must be resolved quickly.

Today’s crises, such as the wars in Ukraine and the Near East as well as the steep increase of immigration from outside the EU are powerful catalysts. The German and French governments have asked twelve jurists, political scientists, and economists, six from each country, to produce a report about the institutional changes that are needed to make the EU fit for the future, without giving up its founding principles, acknowledging the risk that without relevant reform the Union might not survive long-term. A common foreign policy is urgently needed; fiscal policies have to be closely coordinated given that the ECB’s monetary policies need a counterbalance which addresses employment issues, business cycles, social effects and the necessary structural reforms. It has to be accepted that the EU is about to become a world power, even though this has not been intended, and thus requires a robust institutional set-up. The new realities cannot be dodged, and just following the Americans will not do any longer.

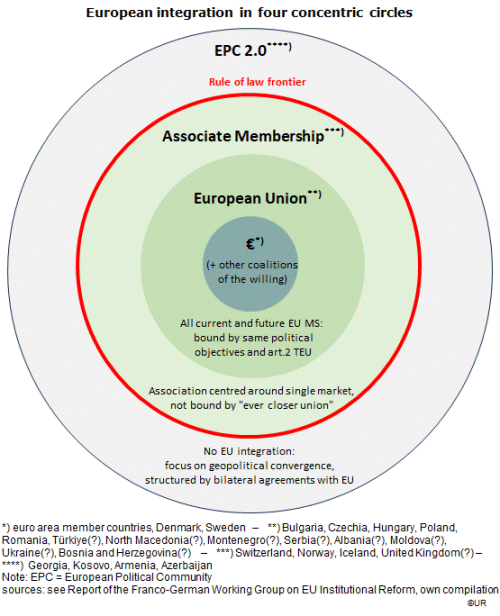

In September the working group has presented its (first) report. On almost 60 pages, and in technocratic style, they propose that EU member states move ahead toward integration at different speeds, with a core group that consists of euro area countries which plan to go ahead with an ever closer union, ie, in the direction of a federal United States of Europe, without being held back by the other member countries. Added to that is a group Number 2, comprised of the remaining EU countries – for which nothing much will change compared to the status quo. In group Number 3 are so-called associated countries such as Switzerland, the UK and other democratic European countries which do not plan to join the EU and would thus not be able to take part in the decision making process. Their main interest is participation in the common market.

To quote from the report, „… the basic requirement would be the commitment to comply with the EU`s common principles and values, including democracy and the rule of law. The core area of participation would be the single market. Institutionally, associate members would not be represented in the European Parliament or the Commission but have speaking without voting rights in the Council and would be offered associate membership in relevant EU agencies. They would fall under the jurisdiction of the CJEU. Associate members would pay into the EU budget but on a lower level (e.g., for common institutional costs), with lower benefits (e.g., no access to cohesion and agricultural funds).”

The report draws a thick red line around these three groups. Beyond this line lie countries which want to maintain a good relationship with the EU but are not necessarily able or willing to adopt the full system of principles and values. Whether a country belongs in group 3 or 4 is not specified in the report but will probably be a matter of negotiations – if the report will indeed be the blueprint for Europe’s future one day.

In the end, the core group will significantly boost its relative importance. They are expected to aim for a genuine common government, a much larger budget and their own (two-chamber?) parliament. The report is vague in this respect, just as about which country will belong to which of the four groups.

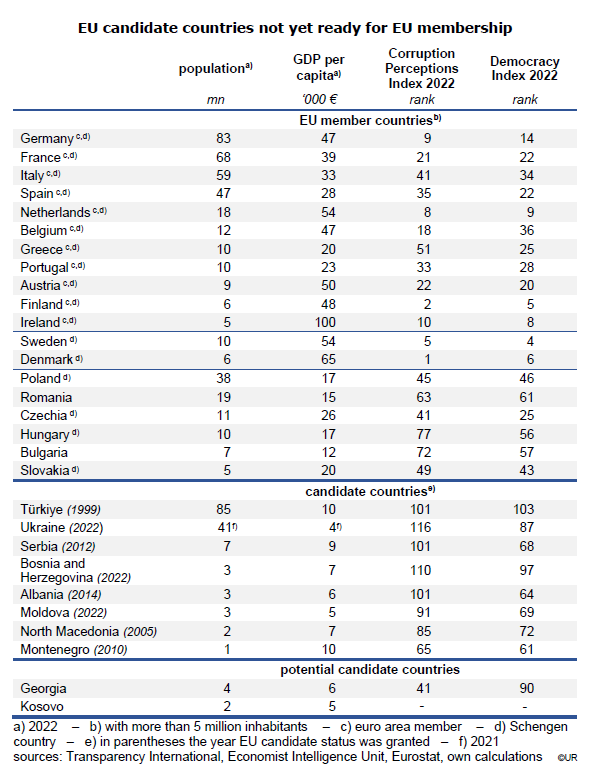

While the EU may be an attractive project for many European countries, especially in economic terms, it is not necessarily one which they want to adopt as a whole. In the near future, it is too ambitious and might strain social cohesion: the differences between their present situation and that of countries in the core group are often simply too large. In some cases the convergence process may last some more decades. Most candidate countries play in a totally different league in terms of democratic institutions and gross domestic product. Seen from Brussels, the further one moves East and Southeast, the more corrupt and poorer are the countries – to put it bluntly, using populist language.

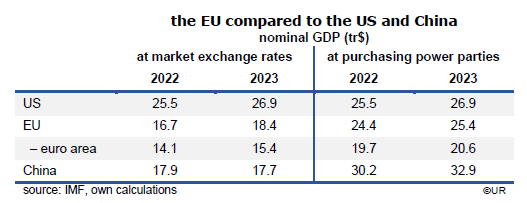

In hard numbers: the nominal per capita gross domestic product of the Netherlands for instance has recently been 5.4 times larger than in Türkiye, six times larger than in Serbia and thirteen times larger than in Ukraine. As to the democracy indicator, almost none of the candidate countries comes close to Belgium, the least democratic country of the euro area. Most of them are governed by autocrats and find themselves also on the lower ranks as far as corruption is concerned. Incidentally, the paragons of probity are Sweden and Denmark, both presently outside the euro area. In terms of income, democratic standards and corruption they are top and could join the core group anytime they want.

The advantages of belonging to the inner circle of member countries are so significant, politically and economically, that societies in the outer reaches of Europe have a very strong incentive to get their institutions on the road toward a core European standard. In other words, if Europe gets serious about the working group’s 4-speed model one day, the whole continent might reform in a positive way, and much quicker than seems possible today.

###

About Wermuth Asset Management

Wermuth Asset Management (WAM) is a Family Office which also acts as a BAFIN-regulated investment consultant.

The company specializes in climate impact investments across all asset classes, with a focus on EU “exponential organizations” as defined by Singularity University, i.e., companies which solve a major problem of humanity profitably and can grow exponentially. Through private equity, listed assets, infrastructure and real assets, the company invests through its own funds and third-party funds. WAM adheres to the UN Principles of Responsible Investing (UNPRI) and UN Compact and is a member of the Institutional Investor Group on Climate Change (IIGCC), the Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) and the Divest-Invest Movement.

Jochen Wermuth founded WAM in 1999. He is a German climate impact investor who served on the steering committee of “Europeans for Divest Invest”. As of June 2017, he was also a member of the investment strategy committee for the EUR 24 billion German Sovereign Wealth Fund (KENFO).

Legal Disclaimer

The information contained in this document is for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice. The opinions and valuations contained in this document are subject to change and reflect the viewpoint of Wermuth Asset Management in the current economic environment. No liability is assumed for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indication of current or future developments. The financial instruments mentioned are for illustrative purposes only and should not be construed as a direct offer or investment recommendation or advice. The securities listed have been selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the issues presented and do not necessarily form part of any portfolio or constitute recommendations by the portfolio managers. There is no guarantee that forecasts will occur.

Read the full article in PDF format here: English.