Stocks and bonds are well supported, but increasingly expensive

introductory remarks

- After the large correction of stock markets in the three months to the end of December last year, investors decided that stocks were cheap again and that central banks would turn, or remain dovish in response to bad economic news and falling inflation rates. And, yes, growth may continue to slow in both advanced and emerging economies, but recessions are quite unlikely. Stock markets have a party these days – globally.

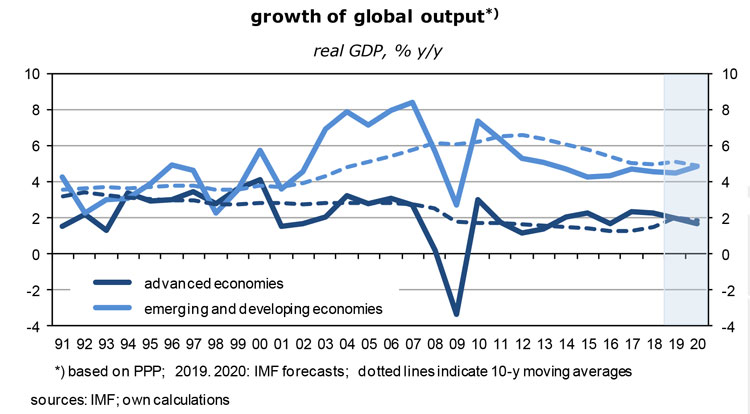

- A slowdown of growth is usually a predictor of weaker corporate profits. Market participants beg to differ. They point out that the IMF has recently forecast that the world economy will grow at 3.5% in 2019 and 3.6% in 2020. The OECD has just said growth would be 3.3% and 3.4%. This is less than last year but still quite close to longer-term averages. It certainly does not look like a recession. If an average growth rate of 3½% can be sustained, it takes global GDP just 20 years to double in size. Growth is still robust.

- According to analysts surveyed by Bloomberg, U.S. per share earnings will rise by 10% y/y over the next four quarters, and by another 11% in 2020. As an aside, this is once again far more than the likely increase of nominal GDP; it suggests that the income distribution will move further in the direction of capital, at the expense of labor.

- Things are not much different in other markets. Profits of companies in the Euro Stoxx 50 are expected to rise by 23%, followed by 10%. The numbers for Britain’s FTSE 100 are no less than 33% in 2019 and 8% in 2020, for the French CAC 40 they are 25% and 9%, for Switzerland’s SMI expectations are for gains of 36% (!) and 8%. Chinese stocks – which have already increased by 26% since the start of the year – will also benefit from rising corporate earnings: 19% and 13%. One conclusion from these numbers is that things will turn out very well this year, and if there is a slowdown it will occur only in 2020. Buy stocks!

- The main outliers are Germany (14% / 11%) and Japan (2% / 8%). Both countries are heavily exposed to foreign developments and thus to the likely slowdown of world trade.

- I tend to dismiss the forecasts of those stock analysts. They are usually too optimistic. I have yet to come across predictions that profits will decline in the near future and that, by implication, investors should reduce their equity portfolios, or hedge them in a meaningful way, at least as far as broad markets are concerned. Brokers make money when stocks rise and everybody is buying, not when they languish or fall. One salient feature of profits is that they can rise for many years in a row, but they can also fall steeply. Will 2019 be such a year? So far, investors have been very optimistic.

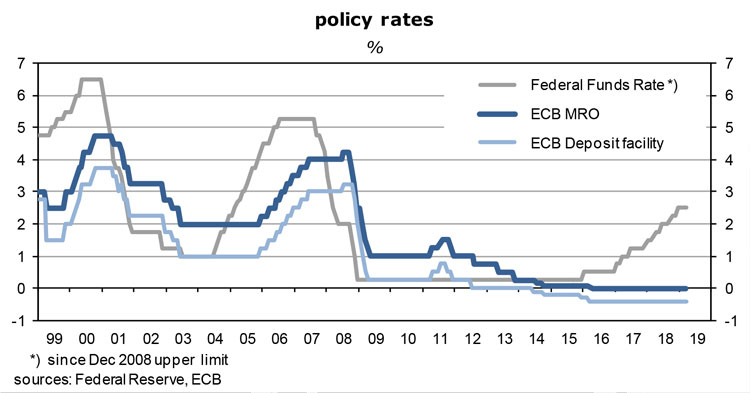

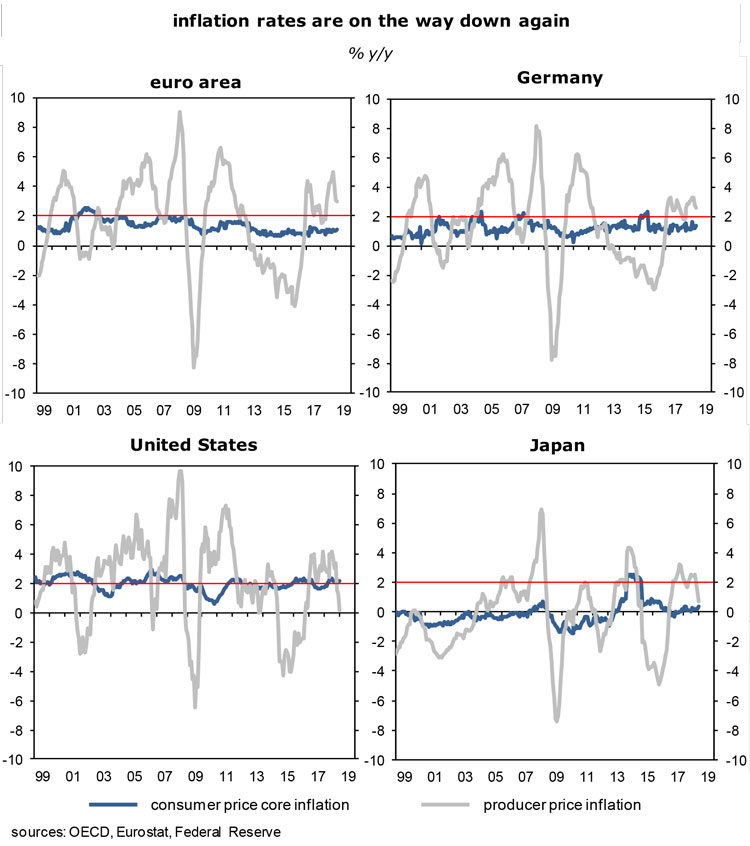

- Economists are mostly too optimistic as well, if not as optimistic as their stock pushing colleagues on the other side of the trading floor. Structurally, they seem to be unable to forecast recessions – unless these are already well under way. There is a consensus, though, that monetary policies will either remain accommodative (ECB, BoJ), have begun to ease aggressively (PBoC) or have stopped to be tightened and will soon start to ease (the Fed). To varying degrees, central banks across the world provide plenty of liquidity and have also signaled that they would not raise interest rates in the foreseeable future, or might even cut them. The risk of deflation may be small, but it is not negligible. Inflation is certainly less of a risk at this point. Most asset classes are therefore well supported by monetary policies.

- Stock markets do not just respond to changes in the business outlook but also to changing relative prices of other assets, such as bonds, cash, exchange rates, commodities or real estate. If valuations are regarded as too high relative to these alternatives, even a positive earnings outlook may not prevent a fall in stock prices.

- In the following I review the determinants of economic growth and inflation, the likely policy response, and what this means for stocks, bonds and the allocation of assets. I look for indications that valuations are appropriate, or whether there are debt-driven bubbles which could lead to a crash and a long period of deleveraging. Might there be a flight to safety, for economic or political reasons?

China – lots of debt, lots of assets, and still going strong

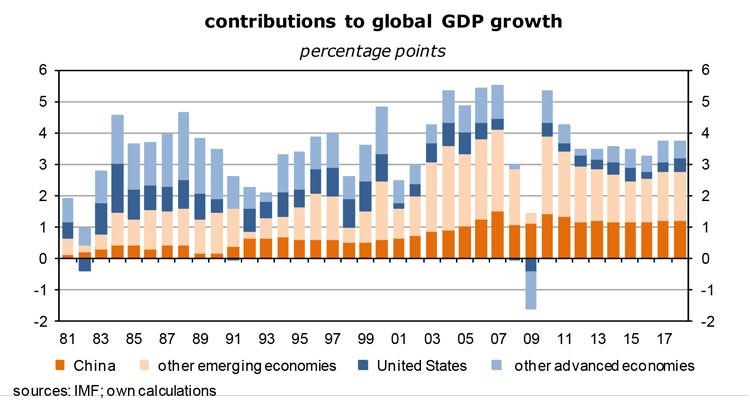

- I start with the three big players, China, the U.S. and the euro area. China comes first because it has been the largest single contributor to global growth for more than a decade, well ahead of America. Have a look at the next graph. China is also the number 1 in terms of foreign trade, GDP (on the basis of purchasing power parities if not yet at actual exchange rates) and CO2 emissions. I remember the saying “if the U.S. coughs, the rest of the world catches pneumonia” – this now applies increasingly to China. Year after year, the country is pulling further ahead of the rest of the world.

- So it matters quite a lot for everybody else should China’s economy continue to lose momentum. Here are some indicators which point in this direction:

- in 2018, car sales have declined for the first time in many years, by 3.1% y/y, to 28.04m (64% more than in the U.S.); in January 2019, sales were down no less than 16% y/y (the market for electric vehicles is very strong, though)

- between May 2018 and Febuary 2019 the new orders Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) has fallen from 53.8 to 50.6, ie, just above the line that separates expansion from contraction; other PMIs have also gone down steeply for more than half a year, especially those on employment; the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index has dropped to 49.2

- imports have been +2.9% y/y in yuan terms, down from +25% y/y in October, a sign of weakening domestic demand (and, of course, the falling cost of energy imports)

- another indication of this is the steep decline of producer price inflation; it fell to 0.1% y/y in January; last summer it had still been around 4 ½%; on the other hand, core and headline consumer price inflation rates have been remarkably stable at around 2% – both have trended down only a little since early 2018

- 5 and 10-year government and AAA-corporate bond yields have fallen by between 100 and 150 basis points since early 2018 and are now in the 3 to 4% range; this is well below the growth rate of nominal GDP and another indicator that China’s economy is far from overheating

- Add to these negatives that there is a trade war going on with the United States. It affects sectors such as autos and electronics, but overall the impact on the economy is quite modest. China is less and less dependent on the external sector. Its economy has become so large and diversified that the main driver is now domestic demand. It would still be a major boost to the economy if the present trade negotiations with the United States could be concluded successfully. Stock markets are betting on such an outcome.

- Here is a short list of the positives:

- wage inflation remains in order of 7 ½% y/y and thus more than five percentage points above CPI; employment may stagnate but workers’ real income continues to rise briskly nonetheless

- both fixed investment and construction value-added have rebounded from a recent spell of weakness and exceed their year-ago values by 6 to 7% (volume terms); industrial production is up 5.7% y/y, comparable to the growth rate of the past four years, though down significantly from the 10 to 15% rates of previous decades – it reflects the ongoing shift from manufacturing to services and is still considerably stronger than what we see in the U.S. and in Europe

- construction activity continues to recover nicely from the lows of 2015/16; there is almost no overhang of unsold properties while new home price inflation of 10 to 11% y/y shows that demand is rather strong

- broad credit (which includes shadow banking) is about 10% higher than a year ago; bank loans alone are up by about 13%; borrowers seem to be confident that they will have enough income to repay their new debt

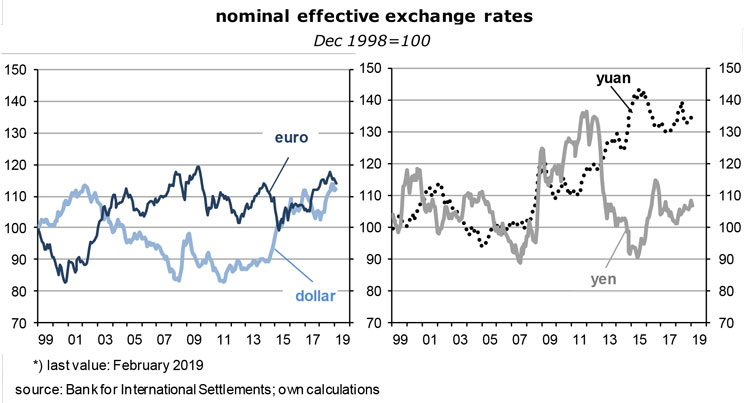

- as pointed out above, China’s stock markets have been up by more than 26 percent since the beginning of the year while the yuan has gradually appreciated against the dollar, from 6.85 to 6.71; I interpret the latter as a sign of goodwill vis-à-vis the United States, and that the authorities are relaxed about international competitiveness

- In general, investors like Chinese assets again. Despite the recent run-up of stock prices the price-to-earnings ratio of the corporations in the Shanghai Shenzhen Index 300 is just 14.4 and thus well below American and European levels (18.3 and 16.2). I don’t quite know how meaningful this metric is, given that government-owned firms have such a large weight in the index. Seen from another perspective: the CSI 300 stock index is still 22% cheaper than at its last high in May 2015, and 33% below the all-time high of October 2007. In other words, stocks are still reasonably priced compared to the past.

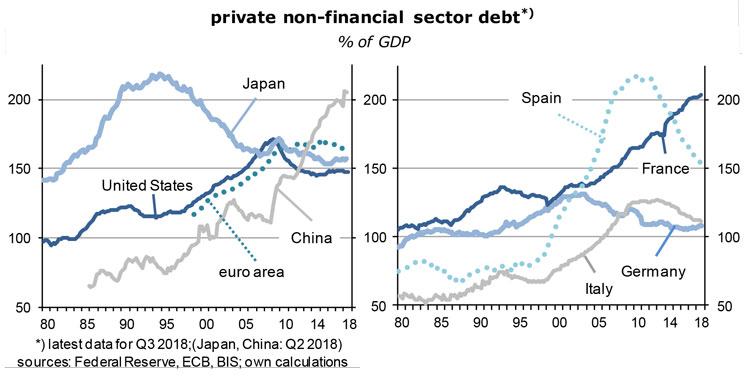

- Since 2016, China’s central bank, the PBoC, has cracked down on financial leverage. In none of the other large economies had debt risen so rapidly relative to nominal GDP during the past decade (see the previous graph). The initial purpose of expansionary monetary policies had been to stimulate borrowing and spending and avoid being dragged into the global financial crisis of 2008/2009. While this had been a resounding success in terms of economic growth – real GDP expanded by 9.6% and 9.2% in those years -, the flip side was that all this stimulus might lead to dangerous price bubbles in asset markets. That’s why policies had turned restrictive three years ago. Leverage is still extreme by international standards, but credit grows now at about the same rate as nominal GDP which means the leverage ratio does not rise anymore.

- Belt tightening has ended, it seems. The economy had lost momentum too fast for the taste of the administration. The recent forecast of the OECD puts this year’s growth rate at “only” 6.2% y/y, after 6.9% and 6.6% in the previous two years; independent institutions such as Capital Economics expect a “true” rate of barely more than 5%. These numbers are close to or below productivity growth which implies that employment is about to stagnate, or could actually decline, a dangerous prospect for the communist government.

- So the focus is no longer on containing the nation’s debt pile but to shore up growth. Deleveraging is out. Policy rates as well as minimum reserve requirements are expected to come down in coming months, and the government has just announced a fiscal stimulus package worth about 2 ½% of nominal GDP.

- Will it work once again? China is certainly not constrained by foreign currency debt – which is just about 15% of GDP and thus well below the central bank’s FX reserves of $3.1bn (the world’s largest). Firms’ foreign currency obligations do not pose a problem from a macro perspective. I also do not see the near-term risk of a Minsky moment when expected returns and/or cash flows from bonds and stocks fall below the cost of funding those portfolios: as I have pointed out, policy rates and thus interest rates in general will fall rather than rise from here on which makes funding cheaper, and neither stock nor bond prices are excessive. The stock rally will continue, especially if a trade war can be averted. This is the most likely scenario.

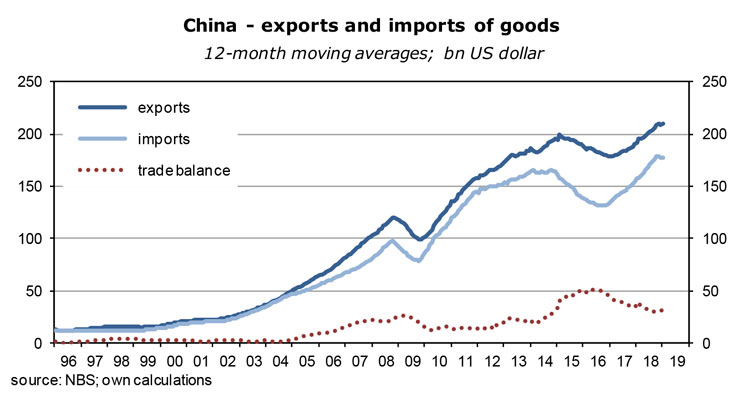

- For the rest of the world this is good news. Since China’s economy expands relatively fast, its imports will gain momentum and thus boost demand abroad. As the following graph shows, the trade surplus is on the way down. The balance on current account which includes services and net income from foreign assets may soon actually become negative. In this regard, China seems to follow the U.S. where GDP growth is also driven by domestic demand while net exports are structurally a drag – and in this way becomes a net importer of capital as well as the growth engine of the world economy. Since the yuan is not yet a reserve currency this will lead to downward pressure on the exchange rate.

American economic policy makers have not yet run out of options

- Turning next to the United States, it is true that the country’s share in global trade and output continues to shrink, especially compared to emerging economies, and China in particular. But in terms of money and capital markets, there is no country that comes near. Just one set of numbers: the market capitalization of the companies in the S&P 500 stock index is presently €21.4tr whereas the combined number of Euroland’s Euro Stoxx 50, Japan’s Nikkei 225 and China’s CSI 300 is just €7.4tr. The dollar remains the world’s most important reserve currency and the ultimate safe haven (perhaps second to the Swiss franc, though?).

- The outlook for the United States is not so bright anymore. The expansion which began in spring 2009 has reached old age and may be near its natural end. As unemployment fell below the level where wages would usually accelerate dangerously, inflation rose toward, and then passed its 2-percent target. From December 2015, the Fed had therefore cautiously begun to tighten the reins, by raising its policy rates from near-zero and reducing its balance sheet which had ballooned during quantitative easing. By now, the effective Fed funds rate has arrived at 2.4%. Bond yields and mortgage rates increased as well even though they remained rather low in real terms.

- The consensus is that monetary policies have worked and will not be tightened anymore, even though the members of the FOMC policy making board still expect three more 25-basis point rate hikes between now and 2020. According to the Fed Funds Futures generated by market participants, the policy rate will actually not rise but fall a little, to 2.3%, between now and then.

- This expectation is a main driver of America’s stock market which has gained almost 11% since the beginning of this year – and is just 5% below its all-time high of September 20, 2018. In other words, the expected slowdown of economic growth should depress stock prices, but because this slowdown will also lead to easier monetary policies, stock prices are on the rise. It could also have been the other way around. Average price-to-earnings ratios are high (18.3) which translates into a modest risk premium of 4.3 percentage points. America’s stocks are thus not cheap, but they are also not excessively expensive. Tech stocks are a different story, though.

- Why could a slowdown of U.S. growth be imminent? Economists suggest two different reasons: the fading of Trump’s fiscal stimulus and the delayed effects of higher policy rates on the long end of the yield curve. The strength of the dollar is another – it dampens domestic demand. A series of recent statistics does indeed suggest that the U.S. economy is cooling:

- in December, retail sales almost collapsed (-1.4% m/m s.a.); such a decline was seen last time in 2008/2009

- vehicle sales in January and February were down from the Q4 average at a seasonally adjusted annualized rate (saar) of 18.7%

- the other rate-sensitive market – housing – is also getting weaker: starts have declined from the interim 1.33m high in May 2018 to 1.08m in December (saar) while the Homebuilder Confidence Index has fallen steeply since late 2017

- industrial production has slowed to an annualized rate of 0.4% over the three months to January, following a rate of 4.2% in the previous three months; meanwhile, the manufacturing PMI survey has come down from 60.8 in August to 54.2 in February

- This is not yet dramatic but justifies the Fed’s new strategy of patience. As it looks, real GDP will expand at an annualized rate of only between 1.5 and 2% in Q1 and thus somewhat below potential. Inflation is unlikely to accelerate in this environment. In its new Interim Economic Outlook the OECD forecasts a real GDP growth rate of 2.6% y/y for this year as a whole, followed by 2.2% in 2020 which implies a significant acceleration of growth in the coming quarters. Once again, a recession is not on the radar screen of the OECD. Incidentally, payroll employment was up 1.9% y/y as well as on a 3-month “saar” basis in January.

- The combination of robust growth and, for the time being, unchanged policy rates is a solid support for America’s stock markets. In addition, interest rates could be lowered a lot if necessary if things turn out worse than expected. The euro area does not have such an option.

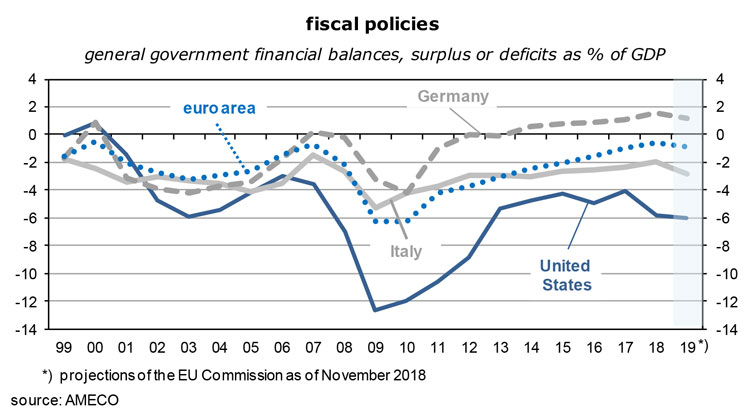

- I sometimes wonder how the U.S. can get away with a budget balance of something like 6% of GDP (see the following graph), a gross government debt to GDP ratio of 106% and a current account deficit of 2 ¼ % of GDP. The country is the world’s largest net importer of capital and thus dependent on the goodwill of foreigners. If the U.S. were Brazil, the persistent twin deficit would regularly lead to runs on the dollar. The main point is that America borrows in its own currency which it can produce at will and free of charge, it can afford to “print money” – or it transfers wealth such as stocks and real estate to foreigners. There can be no run on the dollar, at least not yet. To the contrary, the dollar has been super strong for the last four years.

- America benefits from the role of the dollar as a reserve currency, its huge, liquid and accessible capital market and the fact that there is only one federal Treasurer (not 19, as in the euro area). The country enjoys unique privileges which allow it to consume more than it produces and to attract foreign capital on very favorable conditions. As long as foreigners remain convinced that their U.S. assets will not decline in value will they buy and keep them.

- So far they are relaxed because inflation is moderate and stable, with no acceleration in sight. There are virtually no capacity constraints, not even on the labor market: the participation rate of 63.2% is still more than four percentage points below its high in 2000. And the appreciation of the dollar adds to the downward pressure on domestic prices; in January, import prices were -1.7% y/y.

- The bottom line is here that American assets and the dollar itself may be overvalued, but will probably not correct in the near term. Monetary policy makers will respond to any weakness of the economy by cutting interest rates. The time has not come, though. The likely decline of GDP growth in Q1 will not yet prompt them into action, as long as employment continues to boom (which it does). My bet would be that the overvaluation will persist for some more quarters.

euro area as the sick man of the world economy – really?

- Forecasts for euro area growth and inflation have been revised down by large margins. Yesterday, the ECB reported that this year’s real GDP will only be +1.1% y/y, followed by 1.6% and 1.5% in 2020 and 2021. Two days earlier, even lower growth forecasts were published by the OECD: 1.0% for 2019 and 1.2% y/y in 2020, with Italy at -0.2% in 2019, and Germany a poor 0.7%. Italy is the poor man of the euro area, and the euro area is the poor man of the world economy.

- According to the staff of the ECB, inflation will drop to 1.2% in 2019 and then pick up to 1.5% and 1.6%. The 1.2% rate is plausible in an environment of sub-potential growth, but the following rebound in the direction of the “close to but below 2% target” looks like wishful thinking.

- European stock markets were not impressed by the very dovish statements and forecasts in the press release and, later, by Mario Draghi. Indices were more or less unchanged to somewhat down after the news – which had obviously been anticipated, just as the announcement that “key ECB interest rates (will) remain at their present levels at least through the end of 2019, and in any case for as long as necessary …”. In addition, it did not come as a surprise that new “quarterly targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO-III) will be launched starting September 2019 and ending in March 2020, each with a maturity of two years”. The aim is to stimulate spending money on goods and services, and thus growth and inflation, via easier and cheaper access to bank loans.

- In January, loans to the private sector had been only 2.5% higher than one year ago. In Q4, the growth rate had been 2.9% y/y, just as nominal GDP. In spite of all the monetary stimulus, private borrowers are very reluctant to increase their exposure. When the outlook for the economy is poor, as today, future debt service is regarded more of a risk than in normal times. Put differently, the impact of monetary policy on the demand for goods and services is weak and requires larger doses of the medicine.

- Central bankers are pushing on a string when there is no clear evidence that business will be able to increase revenues, that wages, transfers and other sources of household income will rise, and that inflation will reduce the real weight of debt. Sometimes the government has to step in as a borrower and spender when the private sector has lost its confidence. I am afraid that the present institutional and contractual set-up of the euro area does not allow a major move in this direction, though. That’s a pity.

- Why has final demand been so weak? And how and when will it recover? Why has euro area industrial production ex construction been down by no less than 3.9% y/y in December? It looks as if recession could already be here.

- Mario Draghi yesterday listed the standard reasons: external factors are the slowdown of Chinese growth and world trade, potentially weaker growth in the United States, the likely shock from Brexit and the possibility of trade restrictions reaching Europe. In other words, foreign demand for euroland’s products does not, and will not expand as fast as in the past which in turn creates uncertainty – which in turn is not good for borrowing and spending. And there is nothing that can be done about it.

- On the internal front of euroland, the problems are Italy’s recession (caused by inappropriate fiscal policies, I would argue) and structural problems of the German and the wider European car industry. From a monetary policy perspective, not much can be done about these either.

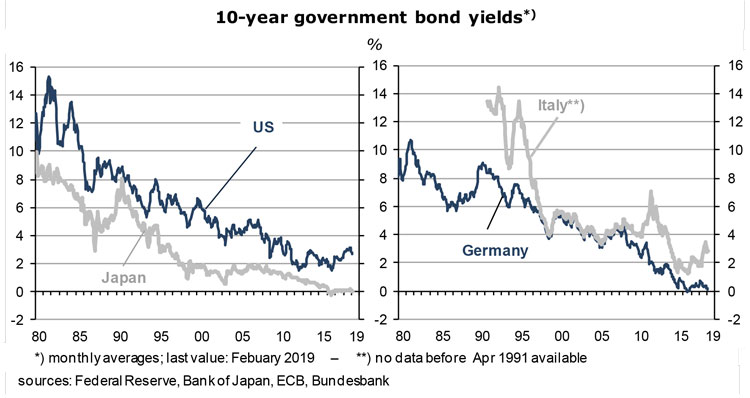

- A factor that policy makers do not like to acknowledge as a reason for the weak economy is the depressed outlook for inflation. The euro area may be on the road to Japanification, characterized in the longer term by near-zero inflation, real GDP growth of about 1% and zero or negative yields on bonds of AAA-issuers. If I am convinced that zero inflation will persist one supporting factor for borrowing disappears – that inflation will help to reduce the real burden over time. A vicious circle develops, as wage increases adapt to zero inflation expectations. Firms also cannot hope to raise their prices by much, if at all on average, which does not make them particularly happy.

- In Japan zero-inflation expectations became ingrained in the long aftermath of deleveraging which followed the bursting of the stock market and real estate bubbles of the early nineties. Even though fiscal policies had been very expansionary at times, aside from aggressive money printing, it did not help much. These policies just prevented even worse outcomes.

- Could the euro area be in a similar situation? Hard to say. Have a look at the graph about “private non-financial sector debt” after paragraph 14 above. Germany has been in mild deleveraging mode for almost 15 years, Spain is moving ahead more aggressively for ten years now, Italy has only just begun the process while France has not even launched one.

- I have often argued that the ongoing intensification of the international division of labor, facilitated by the internet and low transportation costs, leads to an integrated global market for goods and services. Since per-capita income gaps are huge, workers in the poorer parts of the world, especially in Asia, will de facto put a limit on wage inflation in advanced countries. Firms are more flexible than in the past about the location of production – if wage demands are too high, jobs will be moved abroad. This keeps euro area wage inflation in check, and by implication general inflation as well.

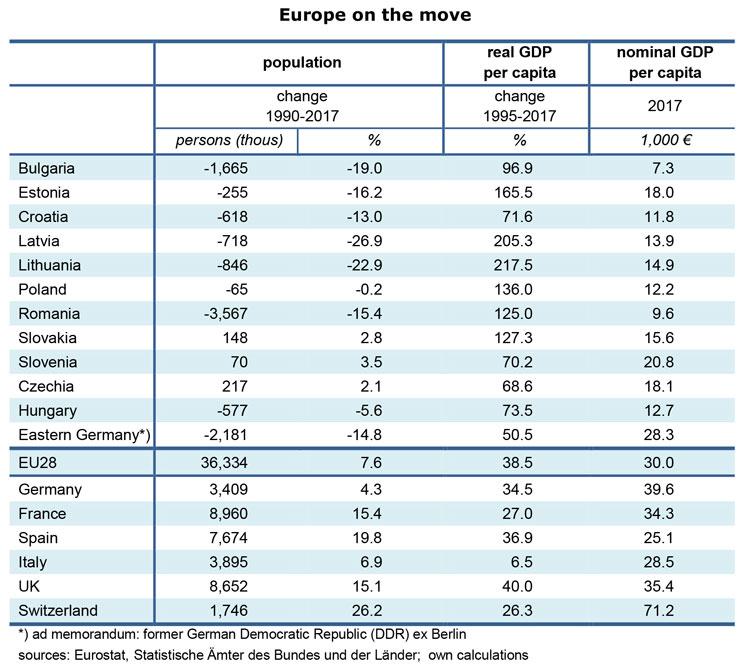

- A euro area-specific reason for persistently low inflation is labor migration. After a short transitory period borders were thrown open for all EU citizens. Workers could freely relocate to places with attractive wages and solid social networks – which they did. As the next table shows, the European population’s center of gravity has moved massively from east to west.

- If somebody leaves Romania and starts to work in Germany, he or she puts downward pressure on German wage inflation and at the same time reduces competition for jobs in Romania and thus improves the income prospects for the “remainers” (but these are probably not so qualified and must at the same time support a relatively larger inactive population at home). This process will last for several decades because the differences are so large – at €41,500 West Germany’s nominal GDP per capita is still 4.3 times higher than in Romania, Switzerland’s is 7.4 times higher!

- International mobility, if it happens too fast, creates large groups of losers and winners. The losers are the problem, of course. In the rich countries, they are typically in the lower rungs of the income distribution, such as hotel or restaurant workers, kindergarten teachers, construction workers, bus and taxi drivers, security personnel, nurses, or street cleaners. They quite rightly blame the immigrants for their low and stagnating wages. In the poor east, social charges rise relative to income while the average professional standard of the remainers suffers as a result of the brain drain – which tends to slow the growth of potential GDP.

- On both sides, east and west, populist politicians can exploit the negative sentiment of people who feel they are on the receiving end of the structural changes caused by migration. Just as international trade is no longer seen as something that is always good, cross border migration cannot be left to the market alone.

- The point is here that a number of factors combine to keep European inflation very low for longer than we thought. There are indeed parallels with Japan.

- Each economy is different and it is therefore not likely that the European story will be just a repeat of what happened in Japan. But the very sticky rate of core inflation, at close to 1% for ten years by now, suggests that over time headline inflation may also settle in this neighborhood. Financial investors need not fear that a sell-out of euro-denominated bonds is imminent. It’s not easy to get used to this thought, but it increasingly looks like the “new normal”.

Read the full article in PDF format:

Wermuths Investment Outlook March 8, 2019